California attorney general to investigate LAPD gang-framing scandal

- Share via

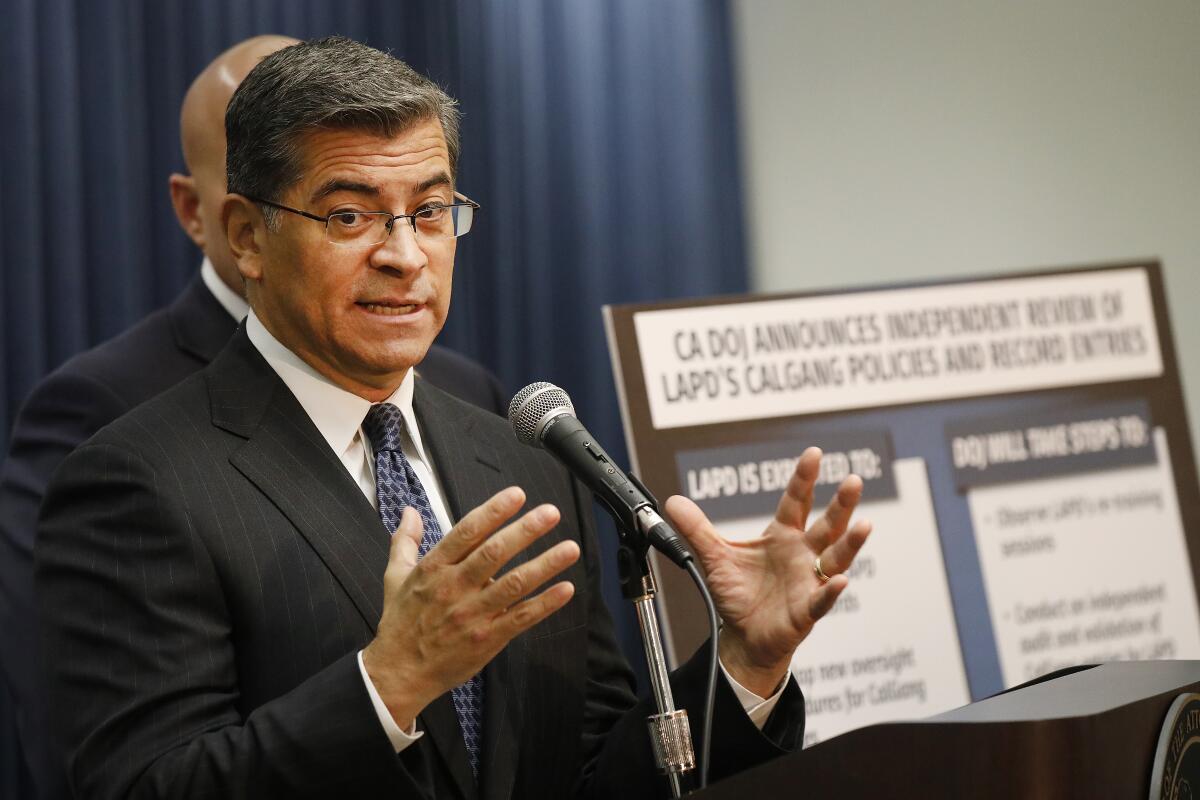

The California Department of Justice announced Monday it will conduct its own investigation of the Los Angeles Police Department’s use of a statewide database of alleged gang members after allegations that officers falsified records to enter people in it.

California Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra said his office has been in touch with the LAPD regarding its use of CalGang, an online index containing detailed information about more than 88,000 Californians suspected of being involved in street crime, and will independently audit some records entered by the LAPD, review the department’s internal controls and policies, and observe its retraining sessions for personnel on the use of the database.

Becerra said that someone’s erroneous placement in the database could lead to them being subjected to unwarranted scrutiny by law enforcement agencies.

“Right now, the LAPD’s inputs are under the microscope,” said Becerra.

The LAPD previously announced it was investigating up to 20 officers in its inquiry of officers that allegedly fabricated information from field interviews to enter people into CalGang. Monday, LAPD chief spokesman Josh Rubenstein said 19 officers are currently under scrutiny. Along with the investigation, LAPD has announced reforms for using the database, including greater internal oversight. In a statement, LAPD Chief Michel Moore said that the gang database is a crucial tool to solve violent crime and that it would fully cooperate with the state attorney general’s office.

“We are committed to holding anyone who falsified information accountable,” he said.

The state action comes amid ongoing controversy over CalGang.

Beginning in 2018, the California Legislature gave oversight of CalGang to the attorney general after a scathing audit found the database lacked meaningful state oversight and contained questionable records — including children who were entered when they were as young as 1. Becerra at the time froze additions to the database while it was reviewed, ultimately purging thousands of records. But thousands more have since been added.

Becerra’s office was also tasked with crafting statewide regulations for the use of CalGang. Those regulations have been the subject of intense debate between law enforcement and community activists, who have said CalGang lacks transparency. Though the rules were slated for completion by Jan. 1, their finalization has been pushed until at least the summer.

At issue is how much and what kind of evidence should be required before someone is added to the database. Currently, law enforcement add someone based on information such as the clothing a person is wearing, the neighborhood where the police encounter occurred and identification as gang members by “reliable” sources.

The public has no access to CalGang, though, and some community activists say those criteria are too loose and subject to abuse — including racial profiling. The database is comprised predominately of black and Latino men.

In a proposal last summer, Becerra suggested cutting back on the reasons a person could be added to CalGang. In December, he reversed on tightening regulations after objections from law enforcement members, who argued their expertise in gang identification should be taken into account, and that such discretion was necessary because gangs have become more adept at evading scrutiny.

Becerra said Monday that his office was continuing to work on the regulations and would accept public comment on the latest version.

The regulations, he said, “should help us build a system that is workable, accountable and helps us get it right.”

This is the first time since taking oversight of CalGang that the attorney general has investigated an agency over its use, Becerra said. He cited the lack of finished regulations as one bar for implementing full oversight.

“Until our regulations are actually implemented, we don’t have the infrastructure we will need to have in order to conduct these investigations,” Becerra said.

The LAPD places more people on CalGang than any other law enforcement agency in the state. From Nov. 1, 2017, to Oct. 31, 2018, the period covered by a 2018 report by the attorney general’s office, it was responsible for 20,583 records — more than 20% of the records in the database.

The current scandal came to light after a Van Nuys mother received a letter early last year from the LAPD saying her son was identified as a gang member during an interview with officers. She believed her son was misidentified and reported it to a supervisor at a nearby police station. Officials then reviewed body-worn camera video and other information, and they found inaccuracies they attributed to the officer.

Moore has said the investigation into the alleged falsifications initially focused on three officers and expanded to others who worked with the original three, and then on to others associated with those officers. He has recommended the criminal prosecution and firing of one officer and has referred that person’s case to the Board of Rights, an internal disciplinary appeal panel. Another officer, Metro Officer Braxton Shaw, is already the subject of a review by the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office.

The LAPD’s data-driven culture has also come under scrutiny by critics who suggest that officers filled in the cards to artificially boost their statistics. The Times obtained what is known as a platoon recap sheet for the Metro Division, which shows that officers were measured daily in 16 categories such as their confiscation of guns, citations and arrests. Field interviews of gang members were among the categories used to measure productivity.

Department officials have said there are no incentives for officers to complete more field interview cards.

“There’s no target [number],” said LAPD Assistant Chief Horace Frank. “There’s no incentive for anyone to breach the law.”

The scandal already led the department to make changes to how it handles CalGang. Now, body camera video is reviewed and compared with officers’ reports of their field interviews before anyone is added to the database. A more robust appeals process that allows people to be removed from gang databases is also being instituted with multiple layers of oversight.

Frank has said that the department has begun training its officers to be much more specific when identifying on a field interview card the evidence that may allow someone to be added to the database. An officer will have to explain, for example, why a particular area should be deemed a gang location if that is a reason for inclusion.

“We’re requiring our personnel be much more specific in their articulation of why some of these criteria have been met,” he said.

Becerra said that his investigation will also include reviewing of body-worn camera video and other recordings, and will expand to records entered across the department, not just in the Metro Division.

Becerra said the recently passed reform legislation on CalGang gives his office the authority to suspend or revoke a law enforcement department’s use of the database if an investigation finds misconduct. Becerra said he could not comment on how many people have been entered erroneously into the database because the investigation was just beginning. He also could not answer questions about how far back his investigation would extend.

“Our role is to make sure that good, accurate information is being entered into the database so that all the agencies that use CalGang … know that the system has integrity,” Becerra said. “The CalGang database is only as good as the information that is put in it.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.