Battery dangers got little attention from Coast Guard despite red flags before Conception fire

- Share via

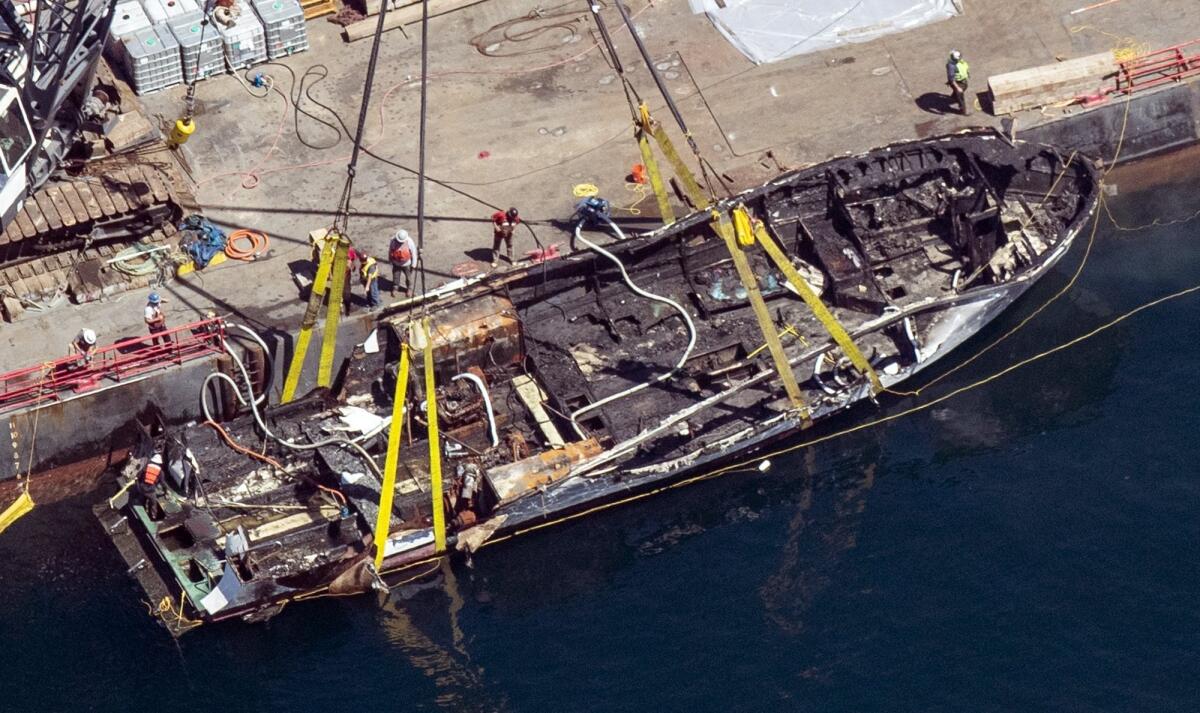

SANTA BARBARA — Nearly a year before 34 people were killed in a fire aboard the dive boat Conception, a second vessel owned by the same charter company began a three-day voyage around the Channel Islands.

Divers on the Vision charged numerous lithium-ion batteries installed in cameras, phones, computers and even underwater scooters with an array of power outlets in the salon area. At some point, one of those batteries began to smolder as it was charging. An alarmed crew member quickly tossed it into the water, preventing the fire from spreading, a witness and several sources told The Times.

The fire underscored the potential dangers of such batteries, which have been banned from cargo areas of commercial planes and become the subject of tighter regulations by the U.S. Navy.

But the U.S. Coast Guard didn’t sound major alarms about the fire risk of the batteries until after the Labor Day fire aboard the Conception, the worst maritime disaster in modern California history.

Officials are still working to determine the cause of the fire, investigating whether it was arson, an electrical or battery fire or some sort of malfunction on the vessel. But some boat safety experts have pointed to the batteries — which have become a staple for divers who use them to power underwater equipment such as lights, cameras and scooters — as a possible starting point for the blaze.

Coast Guard inspectors in California didn’t know about the previous fire aboard the Vision until The Times requested details about it this month.

“In hindsight, it would have been nice to know about it,” Coast Guard Lt. Cmdr. Matthew Kroll told The Times.

Meses antes del desastre en el Concepción, una batería de iones de litio se incendió en su nave hermana. La Guardia Costera ha ido a la zaga de otras agencias en la elaboración de normas para limitar este riesgo de incendio.

After the Conception fire, the Coast Guard for the first time recommended that owners of passenger vessels immediately urge crews “to reduce potential fire hazards and consider limiting the unsupervised charging of lithium-ion batteries and extensive use of power strips and extension cords.”

Glen Fritzler, whose Truth Aquatics firm owns both the Conception and the Vision, believes the batteries were the cause of the Conception disaster.

“I’m telling you the batteries are the issue, and we were never warned,” Fritzler said in an emailed statement to The Times. “I have had top level professional photographers dive with me and they did not understand the dangers.”

Fritzler and his attorney declined to comment further about the fires aboard the Vision or the Conception, citing the ongoing investigations by the National Transportation Safety Board, the U.S Coast Guard and the FBI. He also declined to comment on why his company didn’t report the earlier fire to authorities. Operators are not required to report fires that cause less than $75,000 in damage.

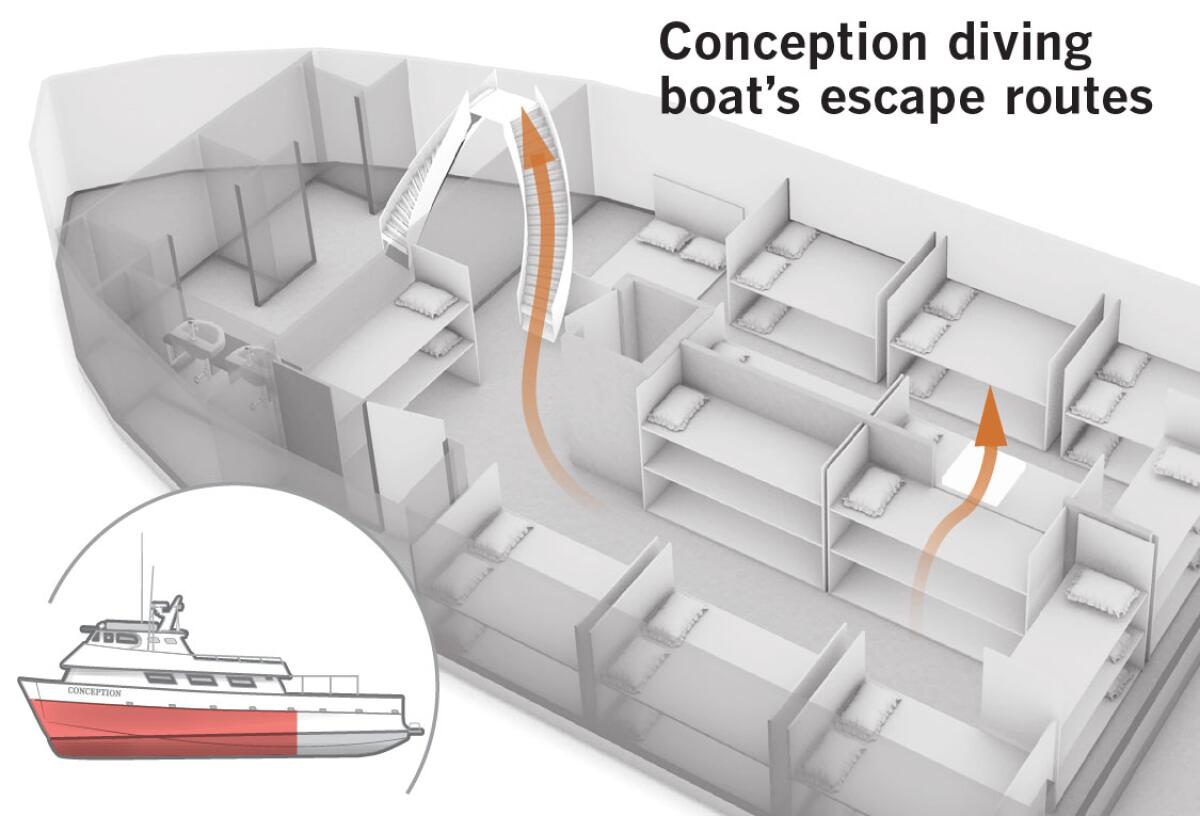

A preliminary investigation of the Conception fire found major breakdowns in required safety procedures on the vessel owned by Truth Aquatics, including inadequate crew training and the absence of a roving night watch at all times while passenger bunks are occupied to alert passengers below deck of an emergency.

Truth Aquatics has also come under scrutiny for how it handled battery charging on boats. Divers who used the Conception previously told The Times that the operator used numerous extension cords to handle the high demand for power to charge various devices.

Passengers often angled for limited charging outlets nestled behind foam-filled, L-shaped benches in the salon areas to power strobe lights, cameras, flashlights and video power packs.

“Stuff is plugged in everywhere,” said Ben Wolfe, a retired Los Angeles County fire captain.

Alarm in aviation

Much of the concern about the dangers of lithium-ion batteries has come from the commercial airline industry.

The Federal Aviation Administration and the U.S. Department of Transportation have expressed concerns because the batteries pack large amounts of energy and can overheat or self-ignite if they are defective, damaged or overcharged, experts said.

The batteries are used in consumer products such as cellphones, laptop computers, power tools, cameras and countless rechargeable electronic devices. Manufacturers each year make millions of devices powered by the batteries.

Lithium-ion batteries create heat when they charge. If not properly vented, the heat from one cell or battery can set off a chain reaction with other batteries, said Thomas Barrera, a scientist and consultant who advised NASA on the topic.

To protect against short-circuiting, batteries contain a thin strip of polypropylene to prevent electrodes from touching. If they short-circuit, heat can be generated rapidly, and once oxygen becomes involved, things can turn bad quickly, Barrera said.

Such fires also burn hot — up to or more than 1,000 degrees Fahrenheit — and could exceed the capabilities of an aircraft’s fire-suppression system and lead to a catastrophic failure of an airplane, the FAA said. Internationally, regulators have attributed four deaths and the total loss of three aircraft to incidents involving fires started by lithium-ion batteries being transported in cargo, in 2006, 2010 and 2011.

After advising global airlines in 2017 to keep the batteries out of cargo holds, the FAA and the U.S. Department of Transportation this year adopted rules allowing passengers to take them only in carry-on luggage. In cargo holds, passengers and airline employees cannot see if a battery fire starts and spreads to other baggage. In the cabin, crew members and passengers can at least see and smell smoke.

The number of lithium-ion battery incidents nationwide remains unknown. But several groups now track the problem. As of Oct. 1, the FAA had logged at least 252 cases since 2006 in which batteries smoked or caught fire inside the cargo hold or passenger area of an aircraft.

Among other things, the fires involved laptops, chargers, e-cigarettes and cellular phones. In at least one case, headphones have exploded on a plane. Aircraft personnel in the U.S. have had to extinguish a device with a smoking lithium-ion battery inside a cabin at least once a month this year.

Airline employees have taken action to prevent catastrophes. In September, a passenger’s bag with a portable speaker on an American Airlines luggage cart caught fire in Dallas. The fire was extinguished, but it burned several other bags, FAA records show.

In August, a passenger’s portable battery charger began to heat up and would not turn off on a SkyWest flight between San Francisco and Texas. A flight attendant placed the device in a battery containment bag and monitored it, FAA records show.

In June, a fully loaded Southwest Airlines plane was evacuated and taken out of service after a passenger’s carry-on bag, with an e-cigarette battery charger and two batteries inside, started to smoke under a seat. A flight attendant used a fire extinguisher to douse the device, according to FAA records.

The U.S. Navy also has severe restrictions on lithium-ion batteries, and in 2017 it banned all vaping devices from its vessels after they sparked numerous fires.

In 2008, lithium-ion batteries being charged ignited a blaze aboard a Navy SEAL mini-submarine in Pearl Harbor. Since then, the Navy has carefully controlled and vetted lithium-ion batteries as larger ones have become part of more equipment on vessels.

The Navy recently established the Navy Battery Development and Safety Enterprise to advance the fleet’s lithium-ion-enabled capabilities. The Navy’s research wing is regarded as among the most advanced when it comes to developing safer batteries to avoid fires.

Two trade groups representing battery makers, developers and suppliers urge caution when transporting the batteries on airplanes, according to their websites. “The industry obviously has an outstanding record for safety. There are millions of electronic devices that people use every day and the record reflects that,” the Rechargeable Battery Assn. said in 2017.

But restrictions on devices that use lithium-ion batteries have not extended to passenger boats.

Until the Conception fire, the Coast Guard had not issued any widespread guidelines regarding their use, although in 2016, a Marine Safety Alert warned boaters about a recall of Samsung phones and provided ways to minimize risks from those batteries overheating.

On Sept. 11, nine days after the Conception fire, the Coast Guard issued a safety bulletin for passenger vessels instructing boat operators to — among other things — “reduce potential hazards from lithium batteries, power strips and extension cords.”

Asked why it issued the alert, the Coast Guard told The Times it wanted to “provide an immediate reminder to owners and operators about regulations related to firefighting, lifesaving, preparations for emergencies, and means of escape.”

A Times review of nearly 20 years of Coast Guard records found the agency repeatedly rejected some recommendations by the National Transportation Safety Board for tougher safety rules.

Last week, three California members of Congress introduced federal legislation to require small passenger vessels to have at least two escape exits, strengthen standards for fire alarm systems and create mandatory safety rules for the handling and storage of phones, cameras and other electronic devices with lithium-ion batteries.

More batteries on diving excursions

Boats such as the Conception and Vision were built decades before the boom in personal electronics and high-end diving gear. On dive excursions, passengers now carry cameras, computers, lights, underwater scooters and cellphones — almost all of which are powered by rechargeable lithium-ion batteries.

Albert Vogel, a 73-year-old from Durham, Calif., was on an overnight trip on the Conception the week before the deadly Labor Day fire. He said the electrical outlets were “dangerously close to the seat cushions.”

“If one of these devices had overheated … it could have easily set fire to the cushions,” he said. “We were not told anything about being careful with charging or any issues related to that. We were just on our own on that, and people used them.”

Don Barthelmess, who taught diving at Santa Barbara City College, said many divers brought power strips to plug in their devices.

“Anywhere there would be a 110-volt outlet, divers would commandeer an outlet,” he said. “People pretty much fight.”

But Barthelmess, who called Truth Aquatics “the Cadillac of diving operations in California,” didn’t think the charging setup — or any other aspect of the boat — raised safety alarms.

“Being on a boat is inherently dangerous, and these are the risks that we accept as people that go diving and go on boats,” he said. “Fires are no exception. No amount of regulations or laws can prevent accidents.”

Greg Lousignont, 70, a former police officer from Peoria, Ill., said that he has been taking trips for three decades on Truth Aquatics vessels and that Fritzler, the owner, is a friend.

When he first started, few divers carted loads of electronic equipment. But that changed in recent years as manufacturers flooded the market with cheaper, mass-produced equipment, he said.

Barrera said these products bring risks, saying that cheaper knockoff cables and plugs don’t have a power management system to stop the overcharging of a battery.

Wolfe, the retired fire captain, was aboard the Vision when the battery caught fire last year. He didn’t see the fire, but other passengers told him about it. Wolfe recalled seeing areas around electrical outlets filled with other items.

He said the batteries and chargers were often stored on seat cushions crowded with other items.

“The space down behind the cushion often had T-shirts, towels and bottles of wine because it was a place to store them and stop them from rolling around,” he said.

That scenario could be problematic, Barrera said.

“If a lithium battery is buried while charging under clothes and on a surface that does not help dissipate that heat, a perfect storm of events can come into play,” he said.

Barrera and other experts emphasized that nothing is inherently unsafe about the batteries as long as precautions are taken. He said that astronauts on spacewalks depend on the batteries and that NASA is able to operate them safely even in the extreme environment of space.

Greater awareness of fire dangers

While divers continue to plunge into the waters off Southern California, boat owners are taking extra steps to limit fire dangers aboard vessels.

Andrea Mills, an education coordinator at Island Packers in Ventura County, said the boating company imposed new safety rules after the Coast Guard issued the warning about lithium-ion batteries in September. Island Packers never encountered any battery fires, but it banned all electronics, not just those with lithium-ion batteries, from gear stored below deck on its four vessels, Mills said. It went a step further than the Coast Guard warning to create an additional safety measure for passengers, she said.

“We are way more aware of the problems in cargo holds,” Mills said. “We did research and read about all the fires in airplanes.”

Ralph Clevenger, who shot photos and videos for Truth Aquatics, said there needs to be heightened awareness about charging devices on boats. He said he is part of an email group with dozens of photographers who have discussed how to educate boat owners about battery dangers.

We “have said, you have got to change things, it’s too dangerous,” he said.

Times staff writer Matthew Ormseth contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.