Okies disappearing from Dust Bowl Festival, replaced by Latino migrants tending California’s fields

- Share via

WEEDPATCH, Calif. — The girl was afraid to speak in class because of her accent.

The clothes sewn by her farmworker mother made her self-conscious. She lived in a field laborers’ camp outside the dusty town of Lamont, and many Californians despised people like her. Go back to where you came from, they said.

“I felt inadequate. I felt like they was all smarter than me, prettier than me,” Pat Rush said. “I was completely, totally intimidated.”

In the 1940s, her family was part of the wave of migrants who fled their farms in the drought-ravaged South and Midwest after the Dust Bowl and Great Depression, traveling west on Route 66 in search of work, and hope.

They were hated newcomers lumped together — people from places such as Oklahoma, Arkansas, Texas, Kansas — under a single pejorative: Okies.

Rush is 84 now. It’s a hot autumn day at the Dust Bowl Festival, the last one after 30 years because its organizers have grown too old, too tired.

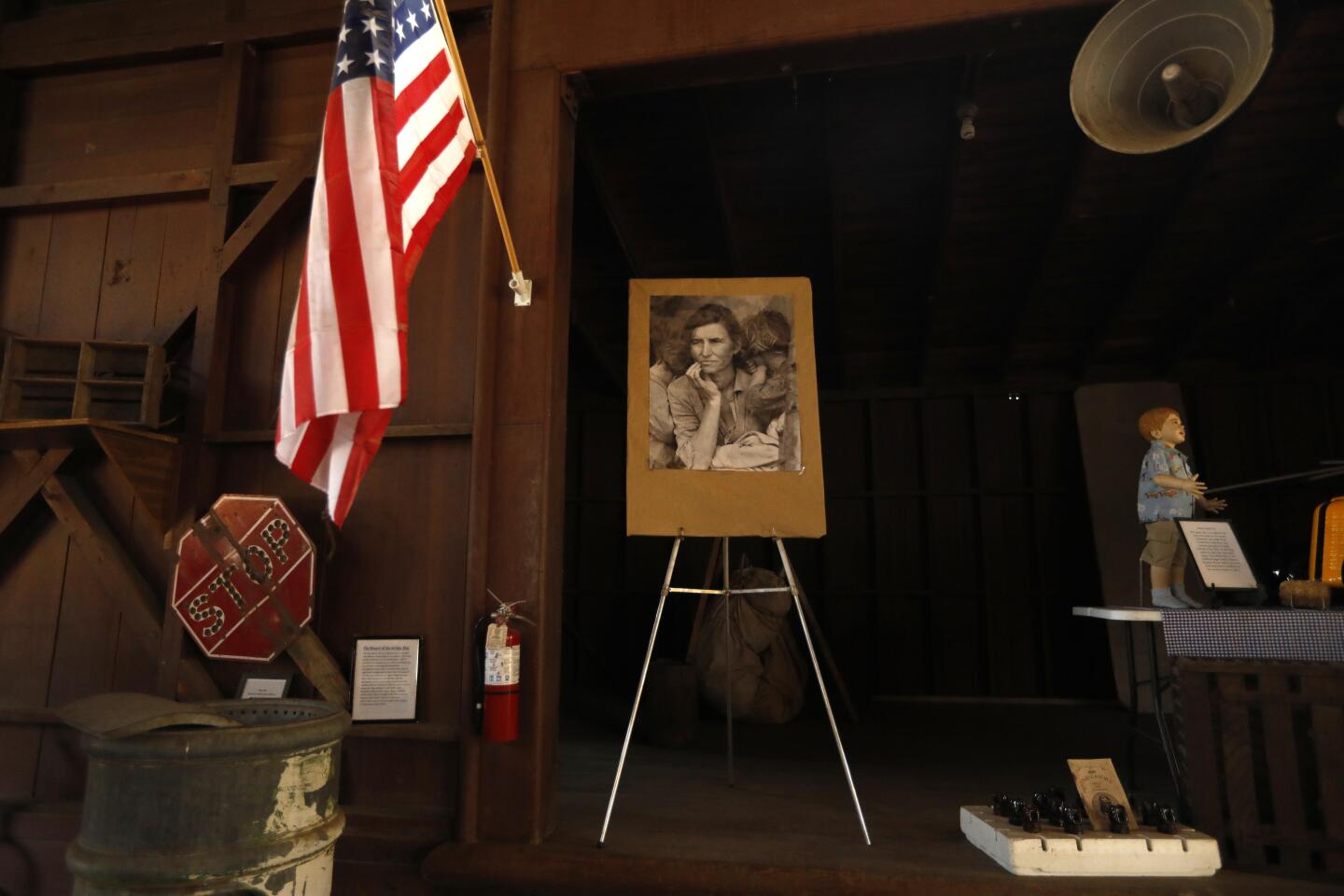

Rush leans on her daughter for support as she walks through the former Weedpatch Camp, the clutch of tents and one-room tin cabins immortalized by John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath.”

She worries that stories like hers will fade, that young people just won’t find them all that interesting.

“I think it’s kind of sad, that it will slowly but surely be forgotten,” she said.

But migrant stories never end. Not in California. Not in America. The names and faces simply change, as do the places from which they came. This too was on display at the Dust Bowl Festival, where many who came to eat biscuits and white gravy and listen to country music were from Mexico, Central America and even Puerto Rico.

The Okies’ history is famously woven into Kern County, the birthplace of the Bakersfield Sound and of Merle Haggard, the Oildale native and son of Dust Bowl refugees whose mega-hit “Okie from Muskogee” became a defiant anthem.

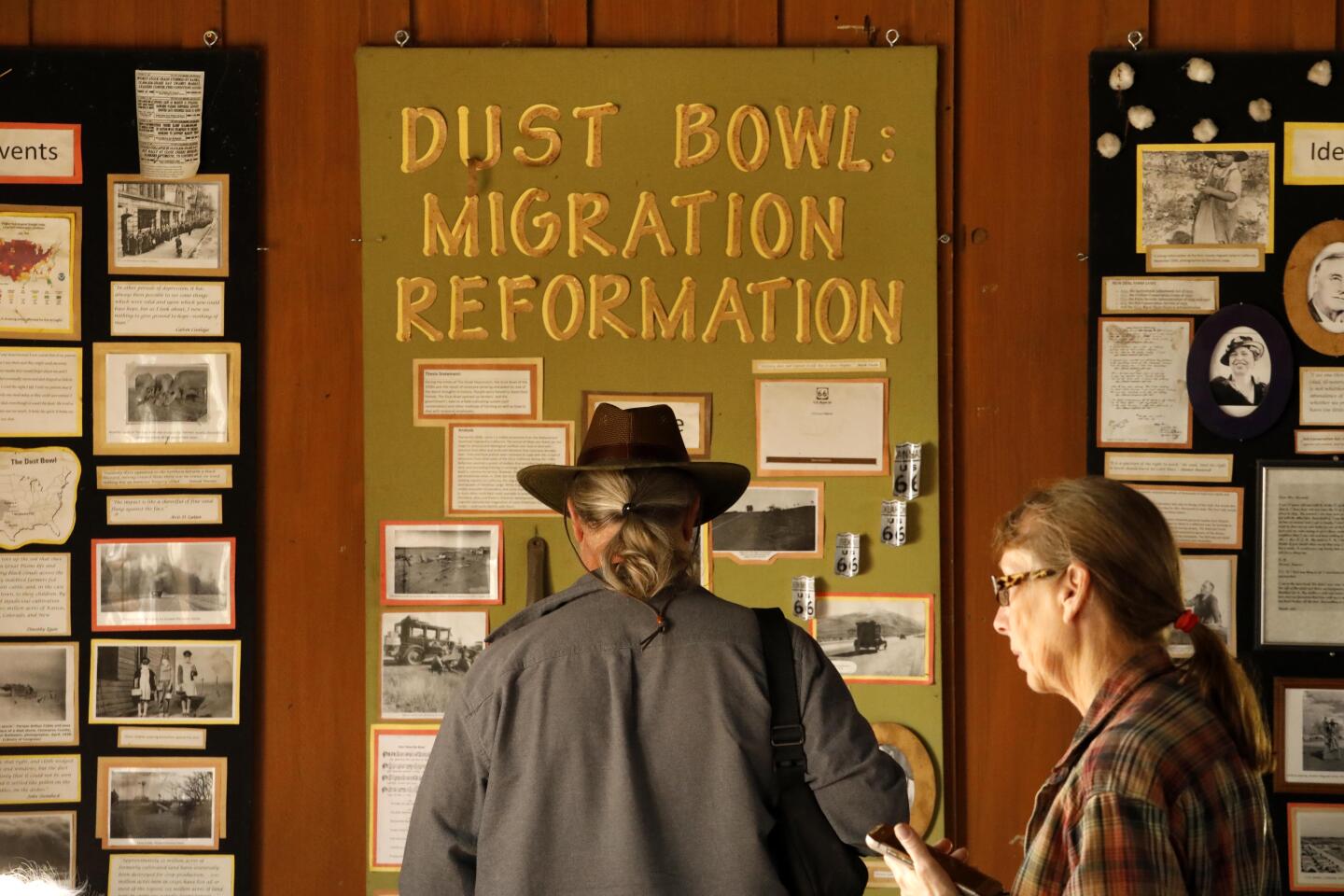

The Dust Bowl Festival, which always felt part family reunion, part county fair, featured line dancing, hayrides, history lessons and large displays of sepia-toned photographs. It ended its run in October at Sunset Middle School, which was built next to the camp in the 1930s as the Arvin Federal Emergency School for migrant kids not wanted anywhere else.

It’s hard to ignore the parallels between the Okies and the pickers in the fields surrounding Weedpatch today. They’re almost all Latinos, often lumped together under one label, spat out by anti-immigration hardliners: Mexicans.

Kern County, one of the most politically conservative counties in California, is 54% Latino and 33% white.

This is the county where Cesar Chavez and Filipino and Mexican grape pickers in Delano staged a five-year strike half a century ago to improve working conditions for field workers. It’s also where current Sheriff Donny Youngblood, a Republican, unsuccessfully called for “anti-sanctuary” policies and defied the California Trust Act that restricts cooperation between local law enforcement officials and federal immigration agents.

At this last Dust Bowl Festival, the people who, in years past, hawked fried okra, bologna sandwiches and Frito chili pie were replaced by high schoolers selling tacos and elote.

Maricela Gutierrez, an eighth-grade teacher at Sunset Middle School, walked with her infant daughter among tables of tchotchkes and displays of old sewing machines and farm equipment. Gutierrez, 28, said she learned little about the Okies while growing up in nearby Lamont.

Almost all of Gutierrez’s students are of Mexican descent. Some are the children of seasonal grape pickers who live a few months a year in tidy little houses at the Arvin Farm Labor Center, migrant housing run by the Housing Authority of Kern County on the site of the old Weedpatch Camp. Gutierrez said they call the site campito — little camp.

Her students are always shocked when she shows them Dust Bowl-era photographs of Kern County farms, with white people stooped over the crops.

“It’s kind of nice to see that commonality, someone that they don’t think that they would have something in common with,” she said.

“Everybody that lives in that camp, they’re all Mexican people. So for the kids to think there were other people that lived here, a few years ago — wow.”

This year, the festival opened with a prayer by former Kern County Sheriff Mack Wimbish, who thanked God for bringing good out of the Dust Bowl: “You moved hundreds of thousands west to a better situation, and through the generations they have just flourished and done well.”

Wimbish was 5 when his family came here from Oklahoma in 1948 in a Model A car. He had an older sister and a single mother with a third-grade education. His uncles had come to California first, found work, then came back to get them.

As a California Highway Patrol officer, Wimbish was assigned to the Lamont area, and he used to joke that they put him out there because he was “bilingual,” meaning he spoke Okie: D’jeetyet? (Did you eat yet?) Go get something out of the turtle hole (the trunk of an automobile).

Weedpatch Camp, also known as Sunset Camp, was built by the Works Progress Administration in 1935, operated by the federal government, and housed about 300 people. The original community hall — the site of church services, dances and potluck dinners — the post office and the library still stand.

From May through October, the Arvin Farm Labor Center houses seasonal, migrant farmworkers on the site of the old camp. This winter, in a first, the empty field workers’ quarters will be used to temporarily house homeless women.

W.C. Stampes lived at Weedpatch Camp for 16 years.

His family fled their shack outside rural Silo, Okla., in 1944, when he was 5. Like the children of Steinbeck’s fictional Joad family, Stampes had never seen an indoor toilet or showers before he arrived at Weedpatch Camp.

Stampes got a work permit at age 12, picking cotton and potatoes.

“Here, we weren’t accepted very well. They thought we were communists, all that sort of stuff,” Stampes recalled. “I never did get out of the camp. It was like a secured, safe area.”

When he was in high school, the girls from Bakersfield “wouldn’t even date you,” he added. They’d say, “Oh, he lives in that government camp.”

But that’s “water under the bridge now,” he said. Stampes, 80, met his wife in the camp, and they raised two children in Bakersfield, where he spent a career working for the county road department. His black-and-white photos were spread out on tables in the Sunset School gym.

He paused and shook his head at an image from 1936. Two police officers stand on a bridge, near a sign reading CALIFORNIA STATE LINE, behind two dejected men they had just turned away.

That year, the Los Angeles Police Department deployed 136 officers, called the “bum blockade,” to the California border with orders to turn back migrants with “no visible means of support.” The Los Angeles Times, which called the migrants “undesirables” and the “hobo horde,” supported the blockade in its editorial pages.

Back then, the skinny, malnourished Okies — vulnerable to diseases such as “valley fever,” a fungal infection linked to exposure to agricultural dust — were seen in California as practically subhuman. One Kern County health officer, in 1937, wrote that “the struggle for existence [had] dulled their untrained intellect and made their bodies gaunt and tough.”

At the festival, elderly couples in jeans and cowboy hats twirled to live country music. Luis Barron stood by the stage, nodding to the music.

Barron, 53, of Lamont said that this area — Arvin, Lamont, Weedpatch,

— always has and always will be a place for migrants because the crops still need to be picked.

He is Mexican American, his family having come from El Paso in the 1960s just before he was born. He identifies with the Okies.

“No matter your skin color, economically, we’re all the same,” Barron said. “We all eat bologna sandwiches. We eat the beans, like everyone else.”

His friend, Pablo Madera, cut in, laughing, saying he was sure going to miss this festival and its food.

“I can eat a taco any day,” Madera said. “Today, I’m eating biscuits and gravy. That’s country!”

Madera, 56, a utility worker for Lamont schools, was born in Puerto Rico, and his father came to California with his grandpa, looking for work, in 1952. That was a time when an estimated 21% of Puerto Rico’s population moved from the island to the mainland United States, amid economic and social changes, in an exodus known as La Gran Migración, the Great Migration.

Puerto Ricans have been American citizens since 1917, but, then and now, they haven’t always been seen that way. President Trump has lashed out about disaster aid designated for Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria, and a White House spokesman this year twice referred to the island as “that country.”

Madera’s father, like the Okie families before him, found work in the fields, lived in the laborer camps throughout the area, and came for Madera and his mother in 1963. For years, Madera had an elderly neighbor, an Oklahoman who had migrated himself. The man has since died, but they had talked every day.

“We all came here. Regardless of where, I always liked the people. I always liked the stories,” Madera said.

Inside the old Weedpatch Camp community hall, with its creaking wooden floors and sunlight streaming through the rafters, Sharon Garrison, a longtime festival organizer, wrapped Pat Rush in a hug. They reminisced about those simpler days of their childhood here, now a bit romanticized, a bit nostalgic.

“Times were so hard, but we didn’t know we had it hard,” said Garrison, 73. She spoke of the joy of a bologna sandwich and how she used to play with sticks in the mud. Then she shared a hard-learned Okie adage, that “You’re not better than anybody, but you’re as good as everybody.”

Garrison’s family was living in Weedpatch Camp when she was born in 1946. Her mother had come with her family to California to Oklahoma in the 1930s. They had bedded down in an overcrowded dirt canal near Lamont, where disease ran rampant, until the health department pushed them out.

Eventually, her mother had a son, Jimmy, but her husband left her, destitute, Garrison said.

Garrison’s father was a widower with three children he’d left behind in Oklahoma while he searched for work. Her father and her mother “were talking over the fence and giving each other their tearful stories, and they agreed to marry,” Garrison said.

“He said, ‘I need a mama for my kids,’ and she said, ‘I need a daddy for my kids.’ And so, they married, and they went back to Oklahoma and got his children. ... They moved here in the camp in one of the cabins, and a year later, I came along.”

Her mom’s cotton sack now hangs in the community hall, and Garrison, a retired cotton gin bookkeeper, still gives tours. The festival, she said, has been so much work for a small group of aging volunteers, but it’s been a labor of love.

“It’s given us a chance to look back and say, ‘Wow, we did do good.’”

Rush, one of eight children, was about 9 when she came to California with her family in the 1940s from Gravelly, Ark. They piled into a car and camped along Route 66, frying potatoes and sleeping on the ground.

“It was really kind of exciting, to be honest with you. I never was afraid when we stopped on the road. You’d think we’d been ‘fraid of bugs, wouldn’t you?”

They moved into a former World War II prisoner of war camp near Ribier and picked cotton and potatoes. Her father had died when she was 7, and shortly before they left Arkansas, her oldest brother, a U.S. soldier who had landed on the beach in Normandy, was killed in combat.

Her mother, Jewell, made little money in the fields. At one point, she went to Bakersfield, trying to get state aid. A man told her to go back to Arkansas. She started to leave but wheeled around and faced him.

“You don’t send me anywhere,” Rush recounted her saying. “I’m free to live any damn place I want to live.”

Her mother, a rule-follower and a stoic woman, said she had just lost her son for this country, she wanted help, and she deserved it. She got it, Rush said.

“I’m very proud of her,” she said.

Rush said she’s lived a blessed life. She met her husband, Ray, at Sunset School. His family lived at Weedpatch Camp after leaving tiny Bokchito, Okla. They married when she was 16 and traveled state to state, working the fields and living in a stationary boxcar before settling in Bakersfield, where he started a construction company.

They’d been married 67 years when he died in April. The Dust Bowl Festival, which he helped start, was dedicated to him this year.

As she walked through the old camp, telling stories about her childhood and her late husband, her grandson, Gabriel Wood, who is half Mexican American, kissed his grandmother on her forehead.

“I love you,” he said. “PaPa would be proud.”

For decades, Rush has kept a folded handwritten copy of a song she wrote for her mother in her billfold.

My mind goes wandering back to a little country road

Across the creek to a small house we called home.

In that house there was more love and understanding

Than a lot of rich kids living in a mansion have ever known

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.