From the Archives: 1932 gold mining in San Gabriel Canyon

- Share via

Gold prospecting in the San Gabriel Mountains started in the mid-1800s and continues today. While on a small scale — compared with Northern California — miners continue to find small amounts of gold dust and nuggets.

In the early 1930s, a mini gold rush hit San Gabriel Canyon. Writer Jean Bosquet reported on the gold prospectors in the Sept. 25, 1932, edition of the Los Angeles Times:

If you can imagine such a thing as a leisurely gold rush, then you can go out along the noisy banks of the East Fork of the San Gabriel River, deep in the canyon bearing that name, and actually see something approximating an unhurried hunt for precious metal.

It never was much of a rush, this quest for San Gabriel Canyon gold which began two years ago and drew thousands of hopeful prospectors with no more prospects than the tailings of a really frenzied rush of another, earlier day.

But the glittering metal has been found daily along the boiling canyon stream since the first of the modern gold seekers pressed into the depths of the canyon, their automobiles and sometimes modern camping equipment in sharp contrast to memory pictures of what had gone on in there 60 years before.

It isn’t much gold that they find, but such as it is, the leavings of that other rush, it has provided today’s seekers with at least a livelihood.

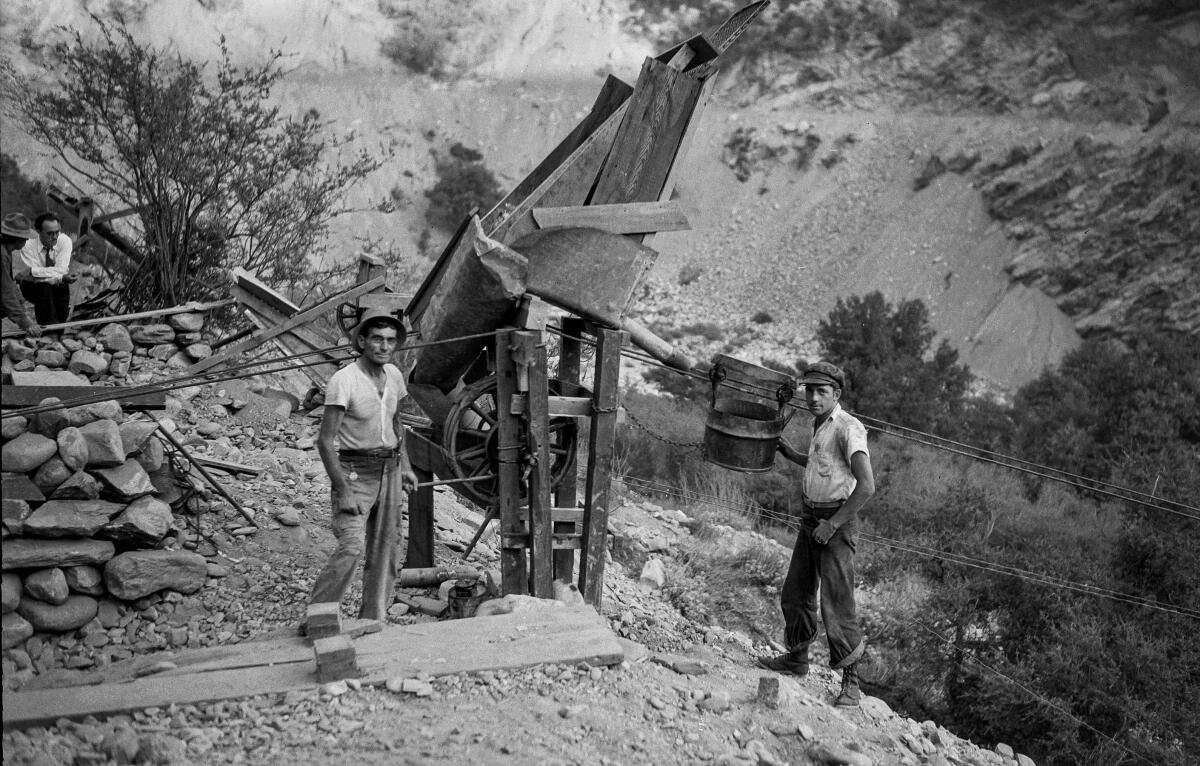

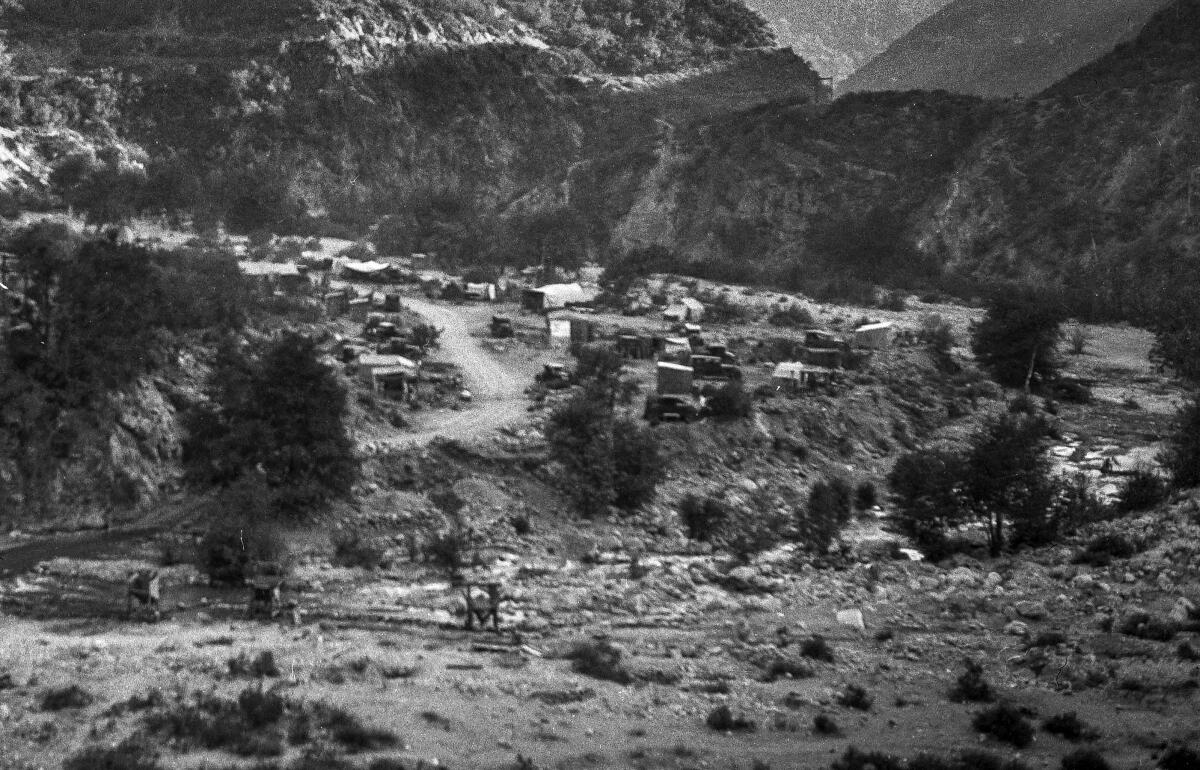

Today there are slightly more than 500 persons scattered along the stream in the canyon, of which 30 are women and a score children. They live in shacks, tents, lean-tos and even in ramshackle automobiles. They form an amazing heterogeneous collection of humans, their numbers being made up of members of many professions, extremely few of them with previous prospecting experience.

Their equipment is as makeshift as their quarters — a bit of wire, an old metal bucket, a shovel, a few lengths of abandoned stovepipe and a perfume bottle being enough for most of them.

From office, factory, store, farm and restaurant have come the men who muck for the tailings of gold to be found on the canyon’s steep sides, where the tunnels of yesteryear’s miners create a honeycomb and the ghosts of a gold-maddened horde stalk by night.

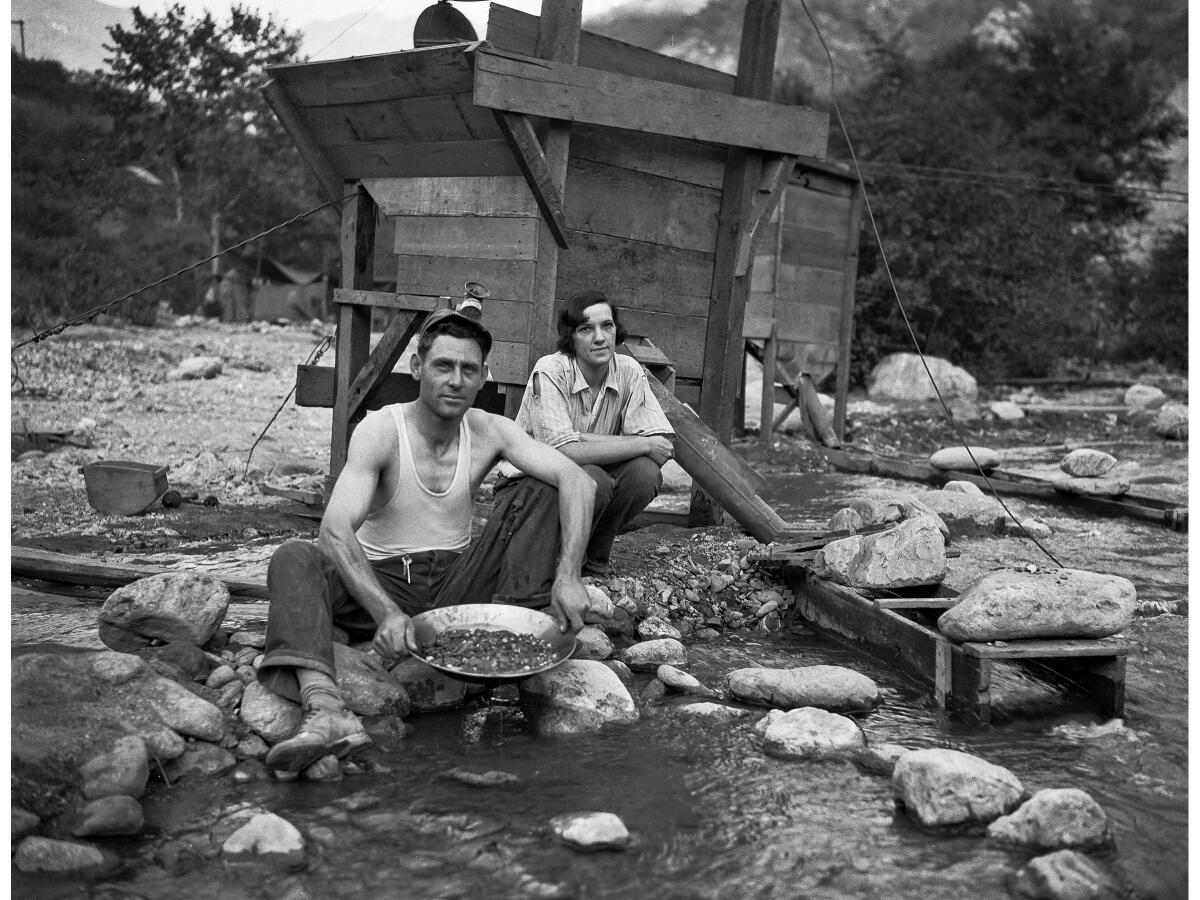

The gold that is found is chiefly dust, few nuggets having been left by those who picked the canyon walls clean more than half a century ago. The precious metal is washed out of the dirt with which it is mixed by a panning, sluicing or washing process in the river below.

A grocery clerk pushed his steaming truck up the five miles or so of riverbed road, his laboring conveyance bounding over boulders and crossing and recrossing the lustily singing river at least seven times before “Upper Klondike” is reached.

The grocer offers $16 an ounce for the glittering stuff carried in the perfume bottles of the miners. He sends it to the mint in Sacramento and clears a couple of dollars an ounce for his trouble.

The man with the grocery truck doesn’t buy as much now as he formerly did. The gold seekers nowadays for the most part prefer to drive to Los Angeles, 40 miles away, and send the stuff to the mint themselves to get its full value. They go in about once each month. …

The government, explains Chief Fire Warden Marshall of the San Gabriel Canyon district, who acts as guide occasionally on canyon tours, permits this digging for gold on the site of the once feverish rush, providing no one tries to clean off the canyon walls in too energetic a style.

“We don’t let ’em use hydraulic drills or anything that would take out the soil in a wholesale manner,” says Marshall. “The tailing in here have enabled a lot of unemployed folk to at least feed themselves since we began letting them work in the canyon. And there’s enough gold left to feed a lot more families if no one tries to get rich all at once. …”

There is no form of city government in Upper or Lower Klondike, the largest settlements of miners and their families. Klondike used to be called Ragtown, but the dignity of some of the gold seekers asserted itself and the name has been changed.

The two settlements are about 300 yards apart and are separated by a bend in the stream. …

While it is hard to obtain from any of the quiet miners a definite average as to what they are taking out of the canyon, with its memories of that hectic earlier gold hunt, the word along the winding river is that it’s about $1.50 a day. ...

::

Seven photos accompanied Bosquet’s story in the Sept. 25, 1932, edition of The Times. The photographer is unknown but was probably a Los Angeles Times staff photographer. I found one print from this story in the Los Angeles Times print archives, but there was no photo credit on the back.

A dozen of the original 4-by-5-inch nitrate negatives for this 1932 article are at the Los Angeles Times Archive at UCLA. I used eight of these images for this post originally published on Sept. 20, 2013.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.