Column: A homeless musician changed my life. I wish I could do more to change his

- Share via

When we met, in 2005, I wouldn’t have guessed we’d still be in each other’s lives this far down the road.

He was playing a violin near the Beethoven statue in downtown L.A.’s Pershing Square. The violin was missing two strings, which didn’t seem to dampen his spirits, and everything he owned was in a shopping cart.

Another thing I wouldn’t have guessed was that all these years later, Los Angeles would still have thousands of people living under the stars, many of them reeling from mental illness as severe as his.

Nathaniel Anthony Ayers showed me a world I knew little about. I thought I could help him, shine a light and show the way for others. I was naively confident the powers that be would respond with whatever it took to do the right thing, the humane thing for all the Nathaniels out there.

What a fool I was.

Almost 15 years later, Nathaniel lives in a locked mental rehab facility, and the rest of us live at the center of an epic collapse of care and a failure of leadership.

Up and down the state, and more so in L.A. County, outdoor asylums are the norm, a raging drug epidemic is on graphic display, and homeless numbers are on the rise despite all the good intentions, the marginal successes and the hundreds of millions invested in a turnaround.

To be honest, I didn’t want to touch the topic this year, because things never seem to change no matter how stories or commentaries are assembled. But they did change. For the worse, thanks in part to a shortage of affordable housing and myriad other catastrophes.

I can’t stand seeing it, but I can’t look away from all the people sleeping on sidewalks and in parks without thinking about Nathaniel, and about the thousands like him who wouldn’t be homeless if we hadn’t let it happen.

Early on, when I wanted to help Nathaniel but had no idea what I was doing, I’d call a psychiatrist for guidance, naively hoping that someone more knowledgeable would have an easy answer. I still have moments when I’m lost and frustrated as I try to help Nathaniel. And I still seek advice. But I no longer expect quick fixes.

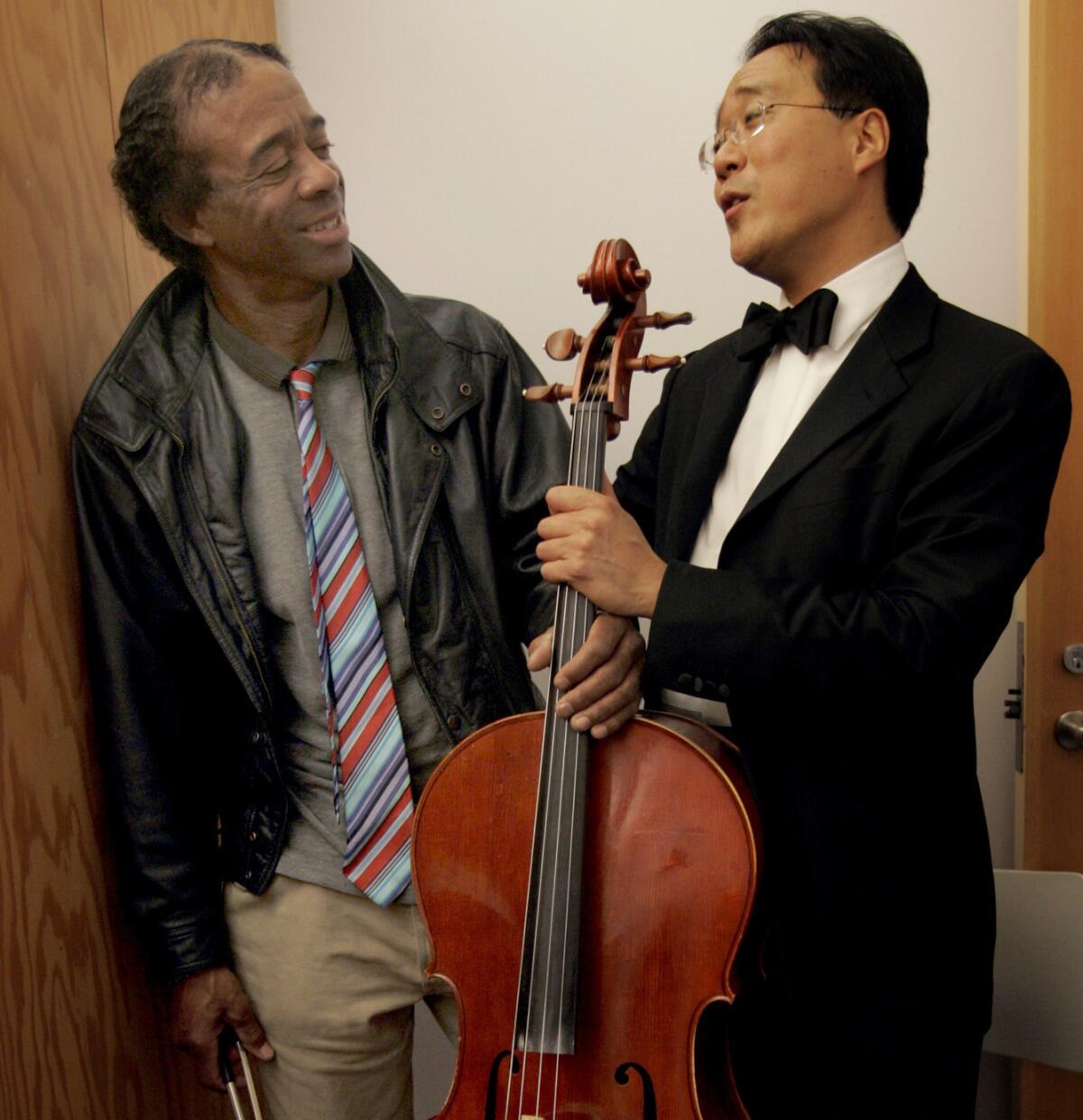

Nathaniel became one of the faces of homelessness through my columns, my book and a movie. We drove to conferences together. Orchestra musicians escorted us to our seats at concerts. We met with Yo-Yo Ma, whom Nathaniel had played with in the Juilliard School student orchestra. We went to the White House together when the Obamas invited Nathaniel to perform.

I’ve felt queasy every step of the way, worried that I couldn’t control the impact any of this would have on him. But the idea all along was to tell a story that looked beyond the illness and into the heart of who he is. He let me into his life; I tried to use that access to make a difference for him and others.

Along the way, Nathaniel became a part of my family, and he delivered on his part of the bargain.

I still struggle to deliver on my end.

Thankfully, there are moments when we disappear, together, into the imaginations of his heroes.

“Let’s listen to Variations on a Rococo Theme by Tchaikovsky,” he said when I visited him a few days ago.

Music remains the only medicine he willingly takes. Absorbed in Beethoven, Bach or Brahms, he is momentarily healed and temporarily freed from his demons. Sometimes, as he’s lifted by a musical swell, his eyes fill. I always wonder if it’s the beauty that tugs at him or if it’s thoughts of what might have been if schizophrenia hadn’t stolen his dream.

“How is everybody,” he always asks before naming every member of my family and making sure all is well.

Everybody in my family is fine.

Everybody in Los Angeles is not.

What I’ve learned from Nathaniel is that no two cases are alike, and that some people are easier to help than others. There’s always been too much emphasis on diagnoses and treatment protocols rather than on the specific needs of individuals, and the service cracks are filled with lost souls.

Nathaniel went from homeless to housed, from isolation to supervision. He had his own apartment for a while in Hollywood. But a solid Monday and a good Tuesday have never meant with him that Wednesday will top the charts. The cycles are wicked, relentless, exhausting. Despite the help of the best nonprofit agencies and most devoted case managers, supportive housing didn’t work for Nathaniel.

I’m grateful that he is housed, fed, cared for and safe. But a locked facility isn’t the solution I envisioned when we met 15 years ago. If all of us pulling together couldn’t deliver a better outcome for Nathaniel, what chance is there for those with no one on their side?

Yes, the challenge is that daunting. Those helped into housing are immediately replaced by waves of newly homeless people. They are victims of job loss, economic reversal, mental illness, addiction.

And so we have tents everywhere, blocking sidewalks and taking over parks, much to the frustration of residents who feel as if they’ve been hit by a storm with no FEMA coming to the rescue.

I don’t want to hear another word about how long it takes to build a unit of supportive housing (two or three years) and how much it costs (half a million dollars or so). For too long now, the explanations have all sounded more like excuses.

I’m tired of hearing that other cities look to us because of how progressive and innovative we’ve been, because we haven’t been enough of either. We need six of everything we know is working and a dozen of what might work better. Who other than us, living in this laboratory, should be figuring out what those more creative approaches might be?

We need more modular housing, more shelters, more medical and mental health services, greater use of neglected public and private property for housing and shelters. The volume of meth, opiate and alcohol addiction is huge, our drug war is useless, and our rehab efforts embarrassing.

And we need people who demand answers to stop saying no when the proposed shelters or the services are near where they live.

I’ve been saying for years that when you shut mental hospitals and never follow through on the promise of community clinics, you create skid rows. And it’s true.

In a few days, I’ll be headed to Trieste, Italy, with a local posse of government and nonprofit officials who are studying a world-renowned mental health model that’s scheduled to be copied in a Hollywood pilot project next year.

I don’t know why Trieste did it and we didn’t, but I’m curious to learn whether that model can work here, where poverty and addiction are bigger problems. I’ve been told that you don’t see people with severe mental illness suffering on the streets in Trieste, fending for themselves. Can you imagine being able to say that about Los Angeles?

In Trieste, as I understand it, there’s an ethos of acceptance, inclusion and community involvement. I’ve seen examples of those concepts in various local mental health agencies. But we need a broad cultural makeover.

One thing I’ve had to do at times, as Nathaniel’s friend, is tamp down my expectation that his situation might significantly improve. I can empathize with families that get worn out waiting for change, and frustrated at the built-in madness of systems that are supposed to help but often do the opposite.

You try to lower expectations, because guilt and hope can destroy you. But then you catch a glimpse, once more, of the human being behind the mask.

Every visit with Nathaniel is opera. He’s on the meds, he’s off. He’s getting along with others, he’s not. He wants to leave, he wants to stay.

Music evens him out. Playing it. Hearing it. Dreaming it.

He breaks my heart, to be honest. I’m inspired by him at each visit, what with his endurance, humility and devotion to music, and then I’m shaken as I walk away, leaving him there, behind a locked door, me with all my freedom and health and places to go.

But I can’t give up.

We’re good at putting thousands of mentally ill people into our jails and leaving thousands more on the streets, even as some of them wither and die.

We need more places in between.

I wonder where Nathaniel would be now if, at 20, when his troubles began, he’d lived in Trieste.

I wonder if Trieste can be translated in Hollywood and beyond.

I wonder if there will be a time when we do the basic things a caring, civilized people do.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.