Could a hurricane lash Los Angeles? 80 years ago, this deadly storm came close

- Share via

September 1939 was a stormy month on the world stage. On Sept. 1, Hitler invaded Poland. On Sept.3, Britain, France, Australia and New Zealand responded by declaring war on Germany. In Los Angeles that month, as residents sweated through an unusual heat wave and nervously watched the storm clouds of World War II gathering overseas, four tropical cyclones that would affect Southern California were born in the eastern North Pacific.

No tropical cyclones had made it north of 25 degrees latitude in the northeastern Pacific basin during all of 1937 and 1938. Then in 1939 there were four such storms in the space of a month, including an unnamed tropical storm that came ashore in San Pedro, dropping torrential rain totaling 5.62 inches on Los Angeles from Sept. 24-26.

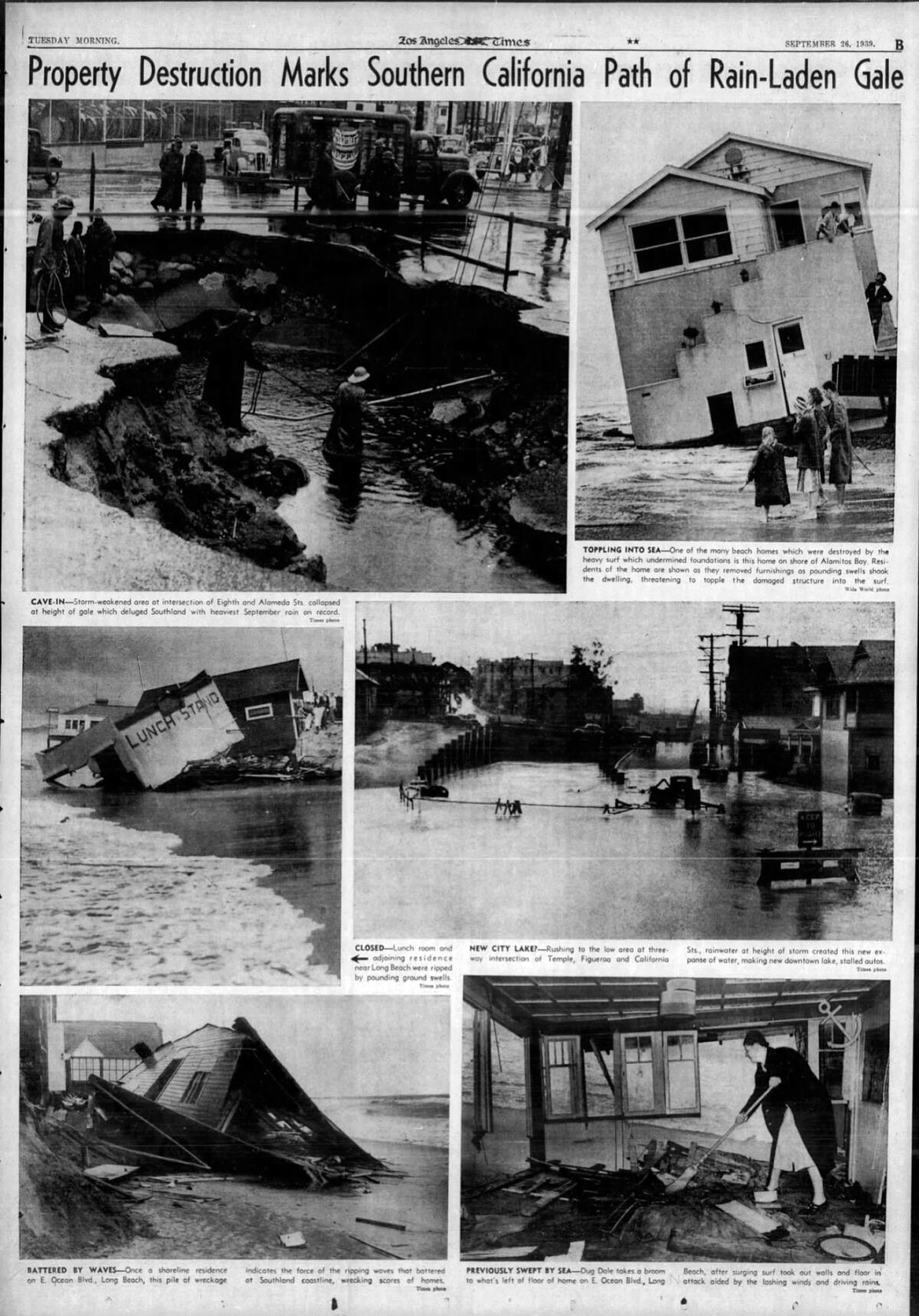

It battered Southern California with wind gusts to 65 mph, according to the Los Angeles Times, damaging boats, structures, utility lines and crops. Forty-five people were killed by flooding throughout Southern California, and an additional 48 died at sea. It’s the only tropical storm to make landfall in California during the 20th century.

That was 80 years ago next month, during the El Niño of 1939-40.

Storms such as this have been given the name el Cordonazo de San Francisco by fishermen in the villages along the Pacific Coast of Mexico. The name means “the Lash of St. Francis,” because they occur in the fall, close to the Oct. 4 feast of St. Francis of Assisi.

As Bill Patzert, retired NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory climatologist, points out, the eastern side of these Cordonazo storms would severely lash the communities on the Pacific Coast of Central America from southern Mexico to Baja. For centuries, the damage was brutal. The Cordonazo lash isn’t felt so harshly or frequently in Southern California.

Various popular explanations suggested that St. Francis used his belt or cord to hit the clouds and make them dump their heavy rain, producing lightning and thunder. The Cordonazo season marks the beginning of the end of the rainy season in Central America. Some stories have St. Francis driving out the devil with his cord, resulting in big storms, thunder and lightning flashes as the devil was chased back into hell.

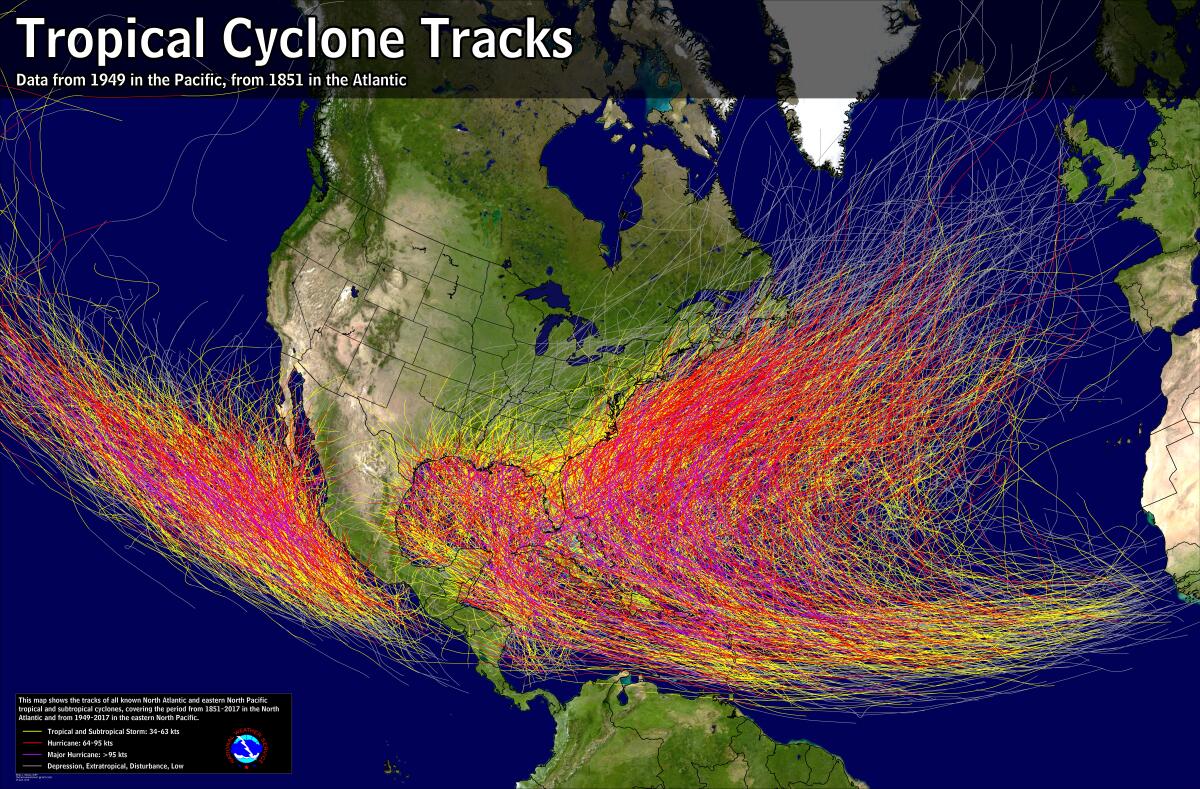

When people think of hurricanes, many think of the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean Sea and the U.S. Eastern Seaboard — in fact, the name comes from “Hurican,” the Carib Indian name for the god of evil — but the most active hurricane region in the world is the western North Pacific, an area responsible for one-third of the planet’s annual average of 79 tropical cyclones.

The second-most prolific hurricane-producing area is the eastern North Pacific, averaging 13 storms per year. It is in this part of the world that L.A.’s September 1939 storm was born.

Hurricanes, cyclones and typhoons are different names for the same type of rapidly rotating tropical system. Cyclonic rotation is counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere and clockwise in the southern hemisphere. The storms are known as hurricanes in the Atlantic and the eastern North Pacific; they’re called typhoons in the northwestern Pacific; and they’re called tropical cyclones in the southwestern Pacific and the Indian Ocean. All hurricanes are cyclones, but not all cyclones are hurricanes.

Tropical cyclones derive their strength from sea surface temperatures of at least 80 degrees Fahrenheit. Most storms that form in the tropical eastern North Pacific are carried by steering currents in a northwesterly direction, where they die out over cooler waters north of the 30th parallel. Most that head west don’t make it to the Hawaiian Islands before fizzling out, although they may delight Southern California surfers with big waves on southwest-facing beaches. They may also send some humidity, clouds or precipitation toward the region.

Occasionally, tropical cyclones curve northward, hugging the coast of Baja California or turning inland. These are the Cordonazo storms.

The first of the series of September 1939 storms formed in the Pacific about 500 miles southwest of Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, on Sept. 2, and made a beeline northward toward Yuma, Ariz., where it dropped 4.45 inches of rain on Sept. 4-6. In California, Needles got more than 5 inches of rain and Brawley recorded 6.43 inches.

On Sept. 5, two more tropical cyclones were born about 1,000 miles apart in the warm waters west of Central America. They followed similar paths along the western coast of Mexico, dying out about a week later over central and southern Baja California. But they sent a plume of tropical moisture north into the Colorado Desert, which is part of the Sonoran Desert in southeastern California, southwestern Arizona and northwestern Mexico.

The fourth in that series of storms — what would be a long-lived Cordonazo — formed around Sept. 15 in the waters off Central America and quickly intensified, reaching its lowest pressure of 970.9 millibars on Sept. 22, when it was about 300 miles west-southwest of Cabo San Lucas, Mexico.

As the storm churned northward, Southern California broiled under a torrid heat wave, with a recorded temperature of 107.2 degrees in Los Angeles on Sept. 20.

On Sept. 23, the temperature reached 100 degrees at the federal building downtown. About 4:40 p.m., a light rain fell, cooling the city slightly. That same day, a thunderstorm dumped 6.45 inches of rain in six hours on Indio, Calif. Moisture from one of the two previous cyclones that had broken up a week earlier south of Ensenada, Mexico, may have fueled that thunderstorm.

After days of intense heat, ominous clouds gathered and thickened over L.A. on the afternoon of Sept. 24 as the fourth tropical storm deteriorated off Santa Catalina Island. The cloud cover pulled the daytime high temperature down to just 81 degrees. A cooling southeasterly breeze arose around noon, lowering the mercury to 67 degrees by 5 p.m. That’s when the rain began. And those cooling southeasterly winds would gust to 50 mph by 7 p.m.

Rain intensified overnight and was especially heavy between 1 a.m. and 8 a.m. on Sept. 25. The rain let up from 10:15 a.m. until 5:35 p.m. that day, then resumed and continued through 1:15 a.m. Sept. 26.

According to The Times, “The storm smashed vessels against piers, breakwaters and beaches in a tragic end to Southern California’s worst heat wave.” When it was all over, damage to boats, structures, power and phone lines was extensive, exceeding $1.5 million. Crop damage amounted to $500,000. Half of the San Clemente Pier in southern Orange County was washed away. ($1 million in 1939 is equivalent to nearly $18 million in 2019.)

Rainfall amounts were impressive: Long Beach reported 4.51 inches; Claremont, 4.89; the Santa Ana River, 4.41; and Mt. Wilson received 11.60 inches over three days, with 9.02 inches of that falling on Sept. 24.

The heat wave and the tropical storm were probably related. As Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at UCLA, says, the storm not only broke the heat wave, it also played a significant part in creating it. Counterclockwise circulation around the cyclone as it approached from the south generated strong east to northeast downsloping offshore winds that drove up temperatures in the L.A. Basin through compression heating. These winds were similar to the region’s autumn and winter Santa Anas, but with a different origin.

For more than a quarter-century after that, no tropical cyclone reached Southern California, although some remnants came close.

Could a full-blown hurricane hit California? It’s not likely. Climatologist Bill Patzert says the “odds are infinitesimal — so small that everyone should just relax.”

There are no documented cases of a hurricane making landfall in the Golden State. Unlike the eastern U.S., where the warm Gulf Stream flows northward along the Atlantic Coast, the California Current carries cool water southward along the West Coast. It literally throws cold water in the face of any tropical cyclones approaching the California coast and the coast of northern Baja California.

In addition, the upper-level winds known as steering currents tend to carry storms to the west and northwest, out into the Pacific and away from California. At lower levels of the atmosphere off the California coast, prevailing winds are northwesterly, creating vertical wind shear that rips hurricanes apart. These northwesterly winds near the surface also promote upwelling, pulling cool water from the deep and pushing warmer coastal water offshore, creating a less-hospitable environment for tropical cyclones.

Downward motion in the atmosphere off the coast of Southern California, as opposed to upward motion vital to the formation of thunderstorms, also discourages formation or continuation of cyclones. This downward motion is associated with June gloom along the California Coast, Swain said.

Nevertheless, against these odds, a number of Cordonazo storms have taken advantage of less common atmospheric conditions and turned northward. Storms usually weaken at about Cabo San Lucas in their northward trek, but a storm that is strong enough and moving fast enough could continue.

Here’s a possible scenario, as proposed by Swain: In September, perhaps during a strong El Niño year, with warm waters in the Southern California Bight, a strong hurricane forms in the Pacific southeast of Cabo San Lucas. It’s a Category 4 or 5 in these warm waters.

Meanwhile, a weak or modest early season North Pacific storm swings out of the Gulf of Alaska, bringing light rain to Portland, Seattle and Northern California. The influence of the low system to the north causes the hurricane to turn to the north, quickly dropping to a Category 2 or 3 in intensity. Storms have been known to backtrack or loop — or even stand still.

By the time the storm reaches the Southern California Bight, it is no more than a Category 1 or, more likely, a tropical storm. But tropical storms pack a considerable wallop in terms of precipitation — as we saw in 1939 — and can generate strong, gale-force winds.

No full-blown hurricane is likely to make landfall in Southern California, although on Oct. 2, 1858, during a moderate El Niño year, a hurricane brushed San Diego before moving off to the west-northwest. It is thought that this was a Category 1 storm at the time. Heavy rain and strong winds were reported both in San Diego and the Los Angeles area.

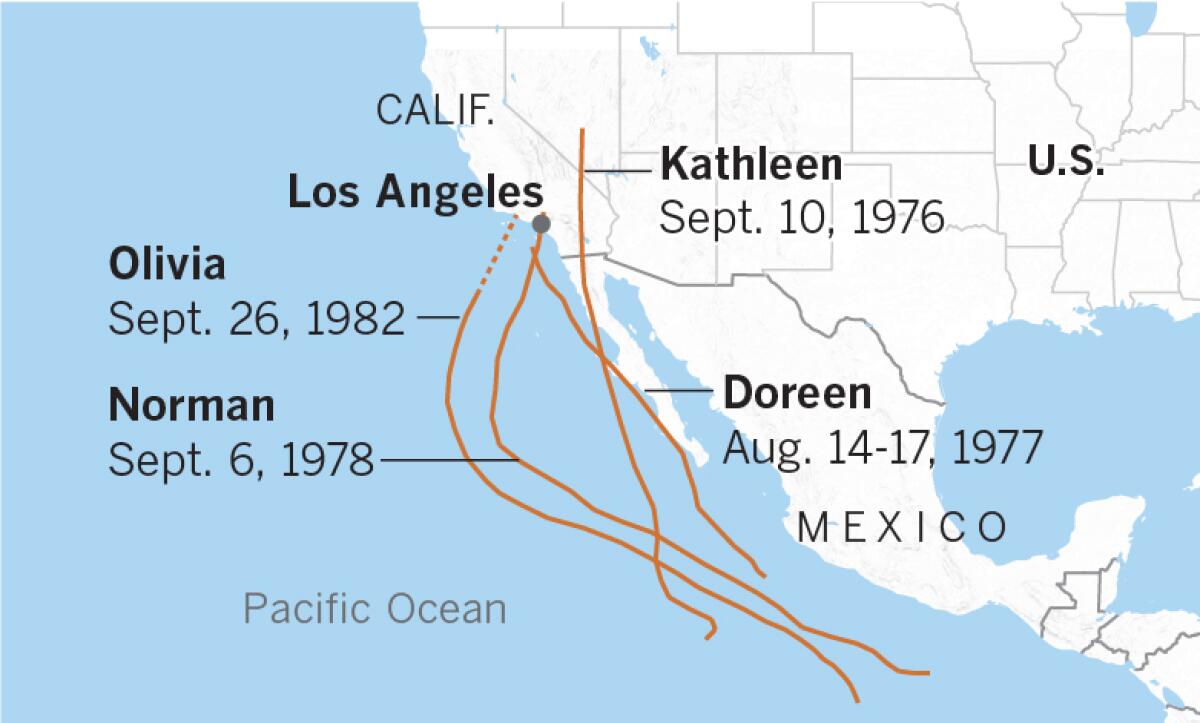

Numerous tropical cyclones have followed the Cordonazo pattern over the years and have affected Southern California and the Southwest. Here are some examples:

Kathleen, Sept. 10, 1976: The first tropical cyclone to hit Southern California after the 1939 storm 37 years earlier, Kathleen dumped 10.78 inches of rain on Mt. Wilson. San Gorgonio Mountain northwest of Palm Springs received 14.5 inches; Lake Arrowhead reported 8.71 inches; the Civic Center in downtown Los Angeles got 1.98 inches. It was during an El Niño.

According to The Times, the storm killed at least six and wreaked widespread destruction in the Imperial Valley and adjoining areas. Ocotillo, near the Mexican border, was hardest hit. A flash flood sent a wall of water 6 feet high and a half-mile wide through the city; 20 homes were destroyed and 70 were badly damaged — at the time, the city had just 100 homes. The Coachella Valley and Palm Desert were declared disaster areas by Riverside County authorities; property damage was set at $10 million, with 300 homes damaged or destroyed in Palm Springs.

Remnants of Kathleen dumped heavy rain throughout the West, with rain and strong winds as far north as Oregon, Idaho and Montana.

Doreen, Aug. 14-17, 1977: The storm was born 100 miles west of Acapulco, again during an El Niño, on Aug.11 and became a tropical storm on Aug. 13. It reached hurricane status on Aug. 14, shortly before passing 30 miles west of Cabo San Lucas. August is usually a dry month in Southern California, but San Diego received 2.13 inches of rain; L.A. got 2.47 inches; 3.78 inches fell at Calexico; 3.87 at Imperial; and 7.45 inches at Mt. San Jacinto, west of Palm Springs. Damage was extensive, especially to agriculture in San Diego and Imperial counties, and the little desert town of Ocotillo was flooded again.

Norman, Sept. 6, 1978: For the third consecutive year, the deserts of Southern California saw flooding when the remnants of Hurricane Norman dissipated off San Clemente Island.

Olivia, Sept. 26, 1982: Heavy rain caused $300 million in agricultural damage when remnants of Hurricane Olivia plowed into the coast near Santa Barbara. This was also during an El Niño year. Moisture from the storm continued inland and eventually caused flooding in parts of Salt Lake City.

In early September 1997, another El Niño year, Hurricane Linda, one of the strongest eastern Pacific hurricanes on record, menaced Los Angeles. Had it hit the state, as had been predicted, it would have been the strongest storm to make landfall in Southern California since the September 1939 Cordonazo storm.

Yuma, on the Colorado River, receives a sizable portion of its rainfall from dying tropical cyclones. Yuma may experience more storms, making it a sort of hurricane alley, because unlike coastal San Diego and Los Angeles — situated on the cool Pacific — it sits just 70 miles north of the bathtub-warm Gulf of California, where summertime water temperatures can reach 90 degrees. This is exactly the kind of fuel that can give a dying tropical storm a new lease on life.

Yuma receives just less than 3 inches of rain annually. In 1963, Hurricane Katherine dumped half of that in one hour.

Unfortunately for the desert southwest, beneficial rain can fall in torrents and is usually accompanied by gale-force winds when it comes from a dying Cordonazo storm.

If there is a silver lining to the September 1939 Cordonazo tropical storm, it’s that before the storm, there wasn’t a government forecast office in Los Angeles. Because Southern Californians were so woefully unprepared for such an event, a Weather Bureau office was established in February 1940.

Times staffers Thomas Suh Lauder, Maloy Moore, Cary Schneider and Scott Harrison contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.