Long Beach’s Iowa Picnic once drew 125,000. This year 160 attended but legacy lives on

- Share via

Cliff d’Autremont had no idea why so many drivers kept blasting their horn at him when he first visited Long Beach in 1968. The Davenport, Iowa, native drove around town in a Volkswagen Bug, so he figured it was just locals mocking his funky ride.

Then it finally dawned on him: Those honkers were fellow Iowans who noticed his Hawkeye State license plate.

“They’d follow me until I parked, then get out of the car and say, ‘I’m from Iowa, too!’” said the now-71-year-old. “‘What county are you from?’”

Soon after, D’Autremont moved to the port city for good and became the latest link in an Iowan migration chain that stretched over a century and so dominated civic life that Long Beach earned the nickname “Iowa by the Sea.” But it wasn’t until 2016 that the Air Force veteran finally attended the diaspora’s most famous tradition: an annual picnic that celebrated its 119th consecutive edition Saturday on the main deck of the battleship Iowa in San Pedro.

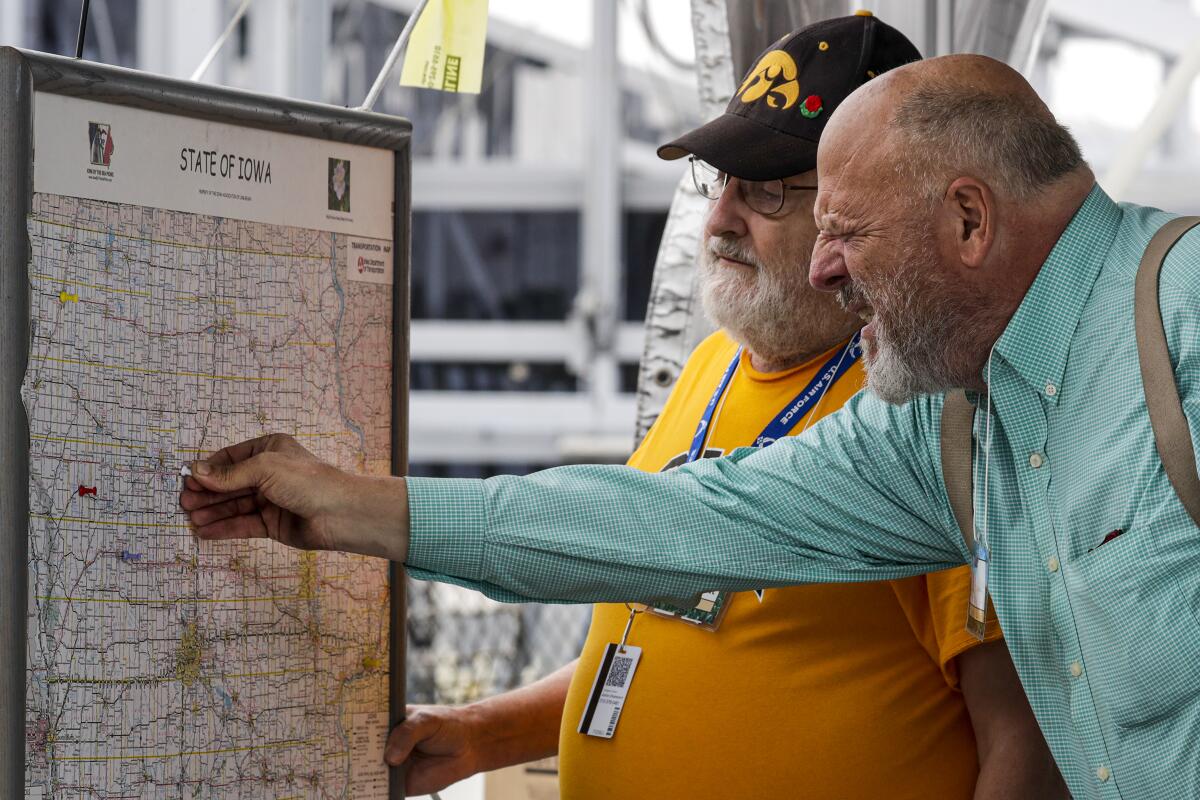

“It’s awesome,” D’Autremont said, as he handed out pins so that 160 or so attendees could mark their hometowns on a map of Iowa. “If you’re from Iowa but now here, you still never really leave it.”

Once one of Southern California’s most celebrated happenings, the Iowa Picnic has free-fallen for decades. What used to regularly attract tens of thousands every year through the first half of the 20th century has struggled to draw crowds over the last 35 years. Local Iowans died, moved away or — worse — fully assimilated and became Californians.

Yet the picnic has continued, willed into existence by longtimers but especially newcomers who, like D’Autremont, eventually find out about it.

“It’ll go on forever,” said Andrea Harrington, who moved to Long Beach earlier this decade and began to volunteer for the picnic a couple of years ago. This time around, she helped to boil corn on the cob. “There’s too many of us here to let it just disappear.”

The five-hour event, run by the Iowa Assn. of Long Beach, featured a blues band, a barbecue luncheon and a group performance of the “Iowa Corn Song,” the state’s unofficial anthem that sees singers raise their hands over their heads at the line “That’s where the tall corn grows.”

Nearly everyone was from Iowa, married to someone from there or had ancestors from the state. Mostly in their 60s and older, they leafed through two binders that listed one-page biographies of famous Iowans like John Wayne, Ashton Kutcher and Ann Landers. For games, adults and children alike tried to guess how many corn kernels were in jars, wrote down their favorite memories of Iowa that an emcee read (one: “the sound of a cow mooing three miles away”) or tossed beanbags at boards that featured photos of the state flower (wild prairie rose), bird (Eastern goldfinch), and rock (geode).

Mostly, everyone caught up and talked about Iowa.

That the picnic continues wows Jeff Morgan, public information officer for the Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs. “We’re grateful and impressed that it’s been going on for 119 years,” he said, “and that this group retains its pride in its home state and wishes to share it with others.”

Thirty-year-old Nate Genrich, originally from Denver, accompanied his 94-year-old grandfather, Howard, who led everyone in the Pledge of Allegiance and has attended the picnic since 1954. “What in Southern California,” Nate said as he checked on three Costco cakes emblazoned with “Iowa” in yellow frosting, “has been going on for 119 years?”

**

The Iowa Picnic is one of the last remnants of an era when Southern California’s most visible migrants weren’t Latinos or Asians, but Midwesterners, with Hawkeyes leading the charge.

Wealthy farmers first came here to retire in the 1880s and quickly spread the gospel of eternal sunshine and good living back home. The first big picnic happened on New Year’s Day in 1887 in Pasadena, when about 400 transplants showed up. They gathered intermittently until 1900, when transplants held one at Bixby Park in Long Beach, to be closer to where most Iowans had settled.

Though other state groups also held their own picnics, the Iowa shindig became a regional sensation. Newspapers in Los Angeles and Iowa covered the affairs, which happened in the winter and summer and drew notable speakers like Iowa governors and native sons Herbert Hoover and California Gov. Frank Merriam.

Bands played; teens courted. Families spread out potlucks. Attendance was so huge that organizers split up picnickers by Iowa’s 99 counties and placed them across the park so that the gathering became a geographic approximation of the state itself. The peak was in 1932, when the Los Angeles Times reported that 125,000 attended the summer edition.

“Other Midwesterners shook off their states when they arrived,” said Matt Lindsay, a recent Cal State Long Beach graduate whose great-grandparents moved to Long Beach in the 1930s but attended the picnic for the first time this year. “Iowans were more like, ‘I’m from there, and I’m going to bring Iowa here.’”

But the tradition withered with the rise of suburbia. By 1984, only 27 people showed up. The picnic moved to Recreation Park, then a lawn bowling club, before relocating to the battleship Iowa in 2014 in an effort to boost attendance.

Its last auxiliary group, the Boone Iowa Society of Southern California, disbanded in 2014, in a meeting that ended with everyone holding hands and singing “Auld Lang Syne.” Present was Don Swenson, a Cedar Rapids native who won the Coming from Longest Distance award for trekking to the banquet from Alpharetta, Ga. He had just bought a condo in Long Beach.

“People were calling its demise way back when,” said the 77-year-old Navy veteran, but he was so impressed with the Iowa Picnic’s legacy that he volunteered to become lead organizer. He started a Facebook page, spruced up a long-outdated mailing list and tasked newer members with responsibilities.

San Pedro resident Lee Meister traveled to the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art and secured permission to display prints of the state’s most beloved painters, Marvin Cone and Grant Wood; the latter’s “American Gothic” stood upon a bale of hay in the shadow of one of the battleship Iowa’s imposing gun turrets. Others got free books, magazines and pamphlets from colleges and cultural institutions; Lindsay was asked to present his senior thesis on the history of Iowans in Long Beach.

“I’m trying to get him acquainted with its ins and outs,” said Swenson, hoping to recruit other young Hawkeyes to eventually take over. “I know what I have to do to get these things done.”

One of the newer faces was Carolyn Chai, a retired physician who lives in Irvine. Originally from Beijing, she went to graduate school at the University of Iowa. A neighbor told her about the picnic, and her Iowa memories were so fond that she signed up to work the gift table, which stocked Iowa flags, T-shirts and coffee mugs.

“Even though people here may not know me as much as others,” she said, “they’ll help just because of my Iowa connection. I’m not a native. I’m not rooted there. But I am a branch.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.