2 quakes in 2 days, no warning from ShakeAlertLA. Now the app is getting reworked

- Share via

A new version of Los Angeles’ earthquake early warning app will now alert users of weaker shaking, Mayor Eric Garcetti announced Wednesday.

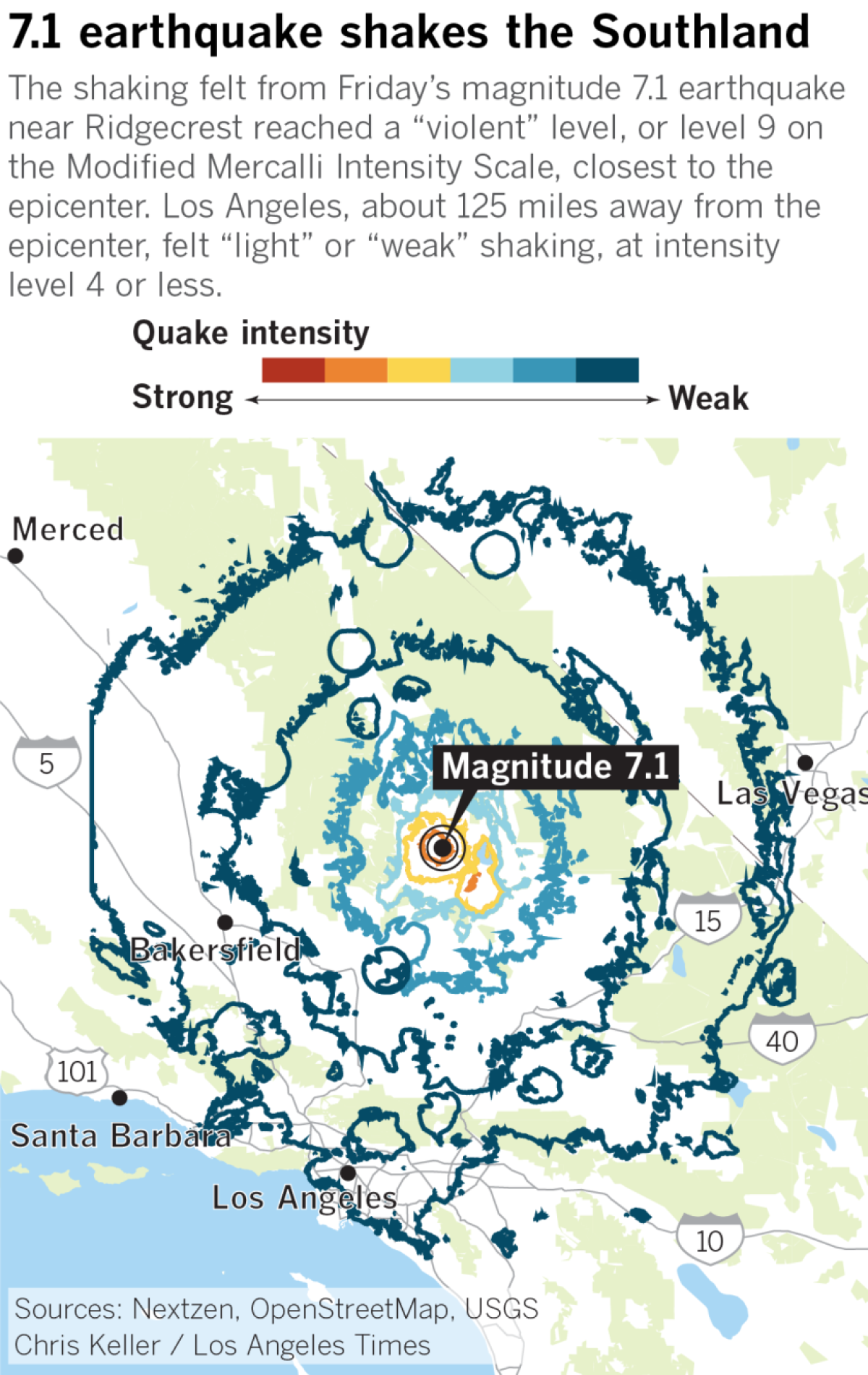

The change comes after many Angelenos were upset they didn’t receive notice before shaking arrived in L.A. from two powerful quakes 125 miles north of Los Angeles on July 4 and 5.

The new threshold will trigger alerts on the city-owned ShakeAlertLA app when “weak” shaking is forecast to arrive in Los Angeles County — a level of shaking, according to the Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale, that is felt quite noticeably by people inside, especially on upper floors of buildings, but may not be felt by other people, especially those outside.

When the Ridgecrest quakes occurred, the minimum level of shaking that would have triggered a public alert for app users was “light” shaking, a stronger level that can rattle dishes and windows and feel like a heavy truck striking a building.

But the city’s app did not send an alert because the U.S. Geological Survey’s ShakeAlert system forecast only “weak” shaking to arrive in L.A. The forecast was slightly off; in fact, “light” shaking was felt across much of Los Angeles.

The lowered threshold could mean that users will get five times more warnings, said Tom Heaton, a Caltech professor of engineering seismology. But, given the public demand for more warnings, the mayor said he thought now was a good time to lower that threshold.

“I think it was smart to start more conservative,” Garcetti said Wednesday at a news conference announcing the change. It’s now clear that people would rather “feel more reassured just to get that alert, even when they know there won’t be damage.”

Scientists familiar with the system thought the earthquake early warning system performed well; they pointed out that, generally speaking, the system was designed to sound an alarm only before shaking arrived with such an intensity that it could produce damage. The Los Angeles area had almost no reports of significant damage from the July 4-5 quakes.

But experts have now concluded that the public would be better served by also receiving warnings to prepare for shaking that, while not damaging, can still be pretty scary.

“Wouldn’t it have been cool to know it ahead of time?” was a common question Garcetti said he received after the quakes.

“People want lower threshold alerts — I think that is loud and clear in terms of what we’re hearing from people,” Berkeley Seismology Lab director Richard Allen told a webinar held by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine last month. “They don’t just want warnings for damaging earthquakes. They want warnings for experienced earthquakes.”

A lower threshold could have given Angelenos perhaps more than half a minute of warning that the shaking was on its way. While the city’s ShakeAlertLA app remained silent, the USGS’ backbone computer earthquake early warning network, ShakeAlert, did detect the July 5 earthquake about 49 seconds before the strongest shaking waves arrived at Los Angeles City Hall.

“That’s part of a sort of generational change that is going on right now,” Allen said. “People would rather have more information than less information, and be able to decide what to do with it.”

The new threshold for ShakeAlertLA means that computers will immediately analyze any earthquake of magnitude 4.5 or greater to determine whether “weak” shaking — intensity level 3 on the Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale — is expected for Los Angeles County.

The old threshold analyzed quakes of magnitude 5 or greater and would generate an alert only if the system forecast “light” shaking for L.A., or intensity level 4 on the Mercalli scale.

Some scientists worry that lowering the threshold too much will cause users to not take early warnings seriously. Because smaller quakes are much more common than big ones, there’s a fear that people won’t act appropriately when they get an alert forecasting a truly devastating event.

“Our fear is that they will become desensitized to the alerts and not act to protect themselves in those instances where they really do need to,” said Doug Given, the USGS earthquake early warning coordinator. “We’re encouraging people to take even the lower threshold alerts as an opportunity to practice what they really ought to be doing, which is to drop, cover and hold on.”

A future option for the app could be to announce different types of warnings — something less urgent for shaking that probably won’t cause damage, for instance. Officials said they can always adjust the threshold if the new setting triggers too many alerts.

More than 800,000 people on the iOS and Android systems have downloaded the ShakeAlertLA smartphone app, which issues warnings for users physically in Los Angeles County when an earthquake strikes. Of those, 300,000 were downloaded after the first of the big Ridgecrest quakes.

The USGS’ West Coast earthquake early warning system is still under construction, with much of the network already built in Southern California and the Bay Area. About half of the 1,675 earthquake sensors needed for a fully operational system are installed, and a combination of federal and state money, as well as private grants, has funded about 85% of the network.

Authorities continue to work on ways to release the alerts more broadly, such as through text messaging and television. But some institutional uses are already in practice, such as automatically opening some firehouse doors before shaking arrives, issuing calls to slow or halt commuter trains and sending alerts to hospitals and police stations.

Scientists have cautioned that the earthquake early warning system in California and the rest of the West Coast will certainly experience errors, such as false alarms and missed alerts.

But researchers, as well as residents of other countries such as Mexico and Japan with active early warning systems, say the false alarms and missed warnings are worth the trouble. Successful warnings can save significant numbers of lives by giving people precious seconds to prepare — such as by dropping, covering and holding on — before shaking arrives.

“We’ve been through a 20-year earthquake drought in California. Most of us are rusty at dealing with earthquakes, and many of us have never dealt with earthquakes at all,” said Heaton, the Caltech professor. “This is sort of the first time we’re back in this, and ... the goal of a system like this is to provide you with some information: ‘Yeah, this is really dangerous,’ or, ‘It’s another aftershock.’”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.