Deputy gangs are officially banned by L.A. County sheriff. Will that change anything?

- Share via

Good morning. It’s Monday, Sept. 23. Here’s what you need to know to start your day.

- A recap of alleged deputy gangs in L.A. County.

- Gov. Newsom signed a new California plastic-bag bill into law.

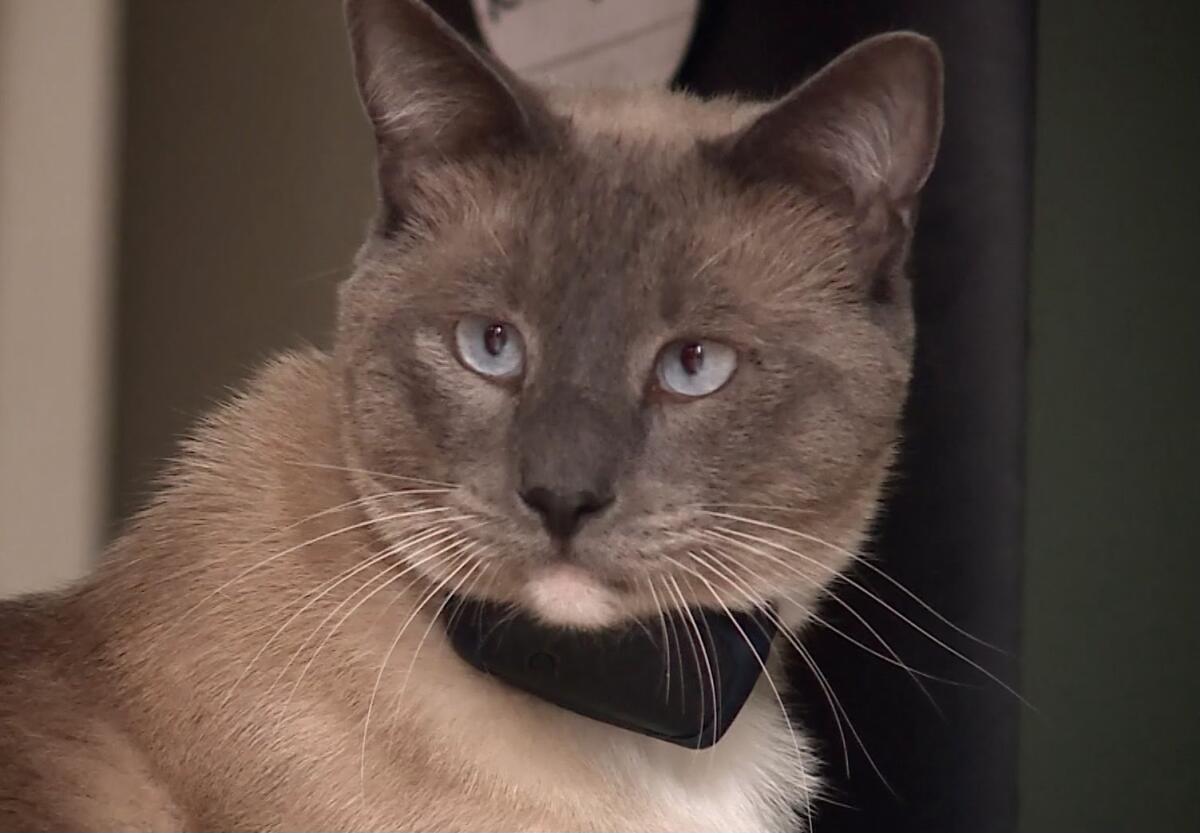

- A 2-year-old Siamese cat made an incredible trek back to his family in California after getting lost at Yellowstone National Park.

- And here’s today’s e-newspaper.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Secretive deputy cliques have operated in L.A. County for decades. A new policy aims to root them out

For decades, secretive subgroups of deputies within Los Angeles County sheriff’s stations generated headlines, probes and lawsuits.

Some call the groups — with names like the Jump Out Boys, Vikings, Banditos and Executioners — cliques. Others called them gangs, alleging they’ve operated outside the law, promoted a culture of violence and racism, and protected their members from accountability.

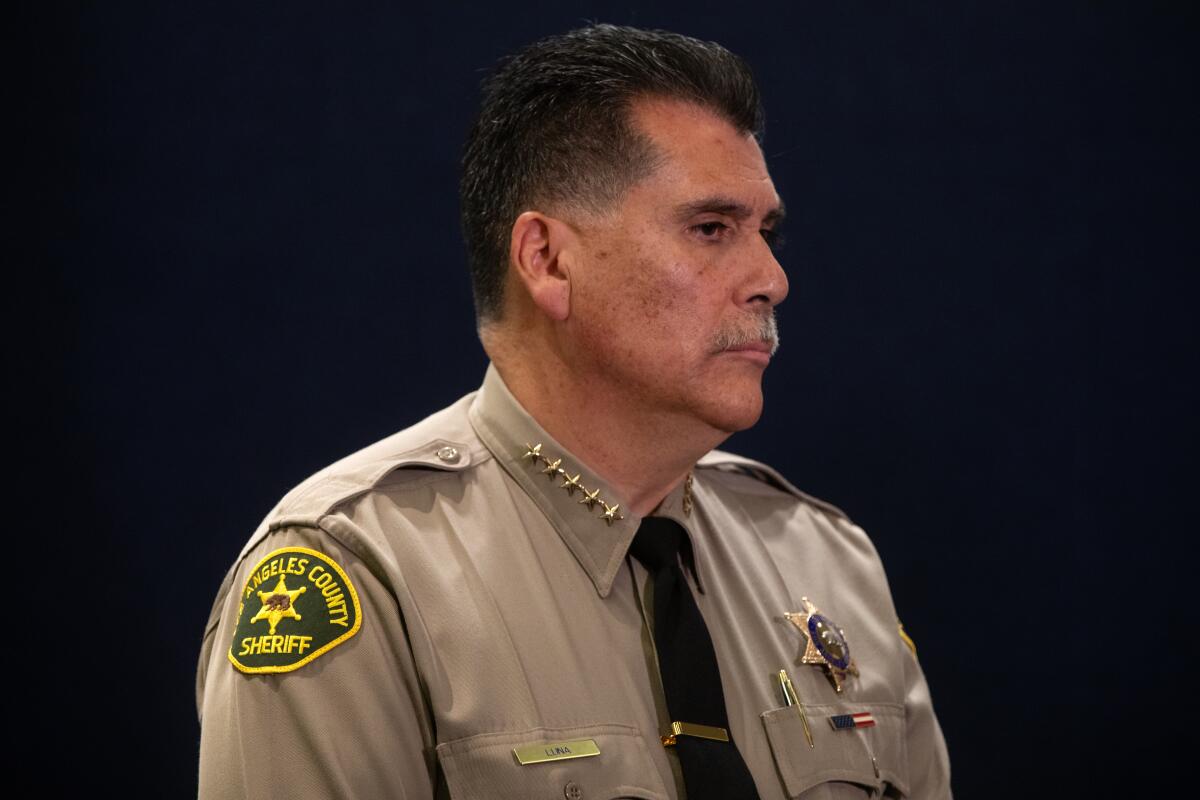

Last week, following years of scrutiny of the department and empowered by a recent state law, Sheriff Robert Luna announced a new policy banning such groups within the LASD.

“The controversial tattooed groups and their alleged misconduct have plagued the nation’s largest sheriff’s department for decades, spurring oversight investigations, an FBI probe and a stream of lawsuits,” Times reporter Keri Blakinger wrote last week. “But leaders have been hamstrung in their efforts to eradicate the inked groups, in part because being in a gang was never explicitly grounds for firing.”

Luna called it “a huge step forward,” though come critics say his policy comes late and have voiced concern that a lack of transparency and retaliation against those reporting misconduct may have a chilling effect.

How long have these groups been around?

The first deputy gangs are believed to have been formed in the early 1970s.

A Times investigation published in 1999 revealed some of the history and resurgence of some groups. Senior officers told reporters it started in 1971 when the Little Devils formed at the East Los Angeles station. More groups were established and grew through the 1980s, many of them at stations with mostly white deputies who patrolled Black and Latino immigrant communities.

“You keep your mouth shut and obey the code of silence,” former Deputy Mike Osborne told Times reporters in that article. “Any illegal acts you witness by other deputies, you don’t say anything. If you’re asked, you say, ‘I didn’t see nothing.’”

More headlines followed in the intervening decades. The department faced a string of lawsuits involving deputies accused of being in so-called gangs, costing the county roughly $55 million in settlement payouts, according to records obtained by The Times.

One common practice among the groups: getting matching tattoos, many depicting skeletons, firearms and other symbols of death.

Former Undersheriff Paul Tanaka admitted under oath in his 2016 criminal trial that he had a tattoo associated with the Lynwood Vikings. A federal judge previously described the groups as a “neo-Nazi, white supremacist gang.”

Tanaka’s ink was reported by The Times back in that 1999 investigation, where it was noted that he got the tattoo in 1987, a year before he was named in a wrongful-death lawsuit over the shooting of a Korean man. That suit was later settled for nearly $1 million.

Tanaka was later convicted and sentenced to five years in prison for conspiracy and obstructing an FBI investigation into deputy jail abuses.

How did the department respond before Luna’s policy?

Lee Baca, who was sheriff from 1998 to 2014, was critical of the groups and their tattoos. He told The Times he “cannot dismiss it as a little club or as a social group.” Baca did not enact any official policies against them during his tenure. He was later convicted and imprisoned as part of the same federal case for obstructing a probe into abuses by deputies in his jail system.

In 2020, then-Sheriff Alex Villanueva put his own policy in place prohibiting employees from “participating in any clique or subgroup that promotes conduct that violates the rights of other employees or members of the public.”

But, as Keri reported, Villanueva’s policy was criticized as ineffective by oversight officials.

“Some said it lacked teeth and wasn’t being enforced, and researchers at Rand Corp. suggested in a county-commissioned report that the department could improve its policy by defining more specifically what was prohibited and requiring deputies to disclose membership in organizations,” she wrote.

Villanueva has continued to deny the existence of deputy gangs, while people in the neighborhoods patrolled by inked-up deputies have long been vocal about their concerns.

When Luna unseated Villanueva in 2022, he acknowledged the existence of the gangs and vowed to root them out of his department. Although he views the new policy as proof of that vow, some oversight officials worry it won’t create meaningful change.

“The real challenge will be getting the LASD leadership to truly investigate and enforce the new policy,” Civilian Oversight Commissioner Sean Kennedy told Keri. “In the past, they have all turned a blind eye to internal gangs and cliques, which is how the gang culture became so pervasive within the department.”

Today’s top stories

Gov. Gavin Newsom wields his pen, signing and vetoing state bills

- Newsom signed a new California plastic-bag bill into law, one that closes a loophole from 2014’s ban that actually led to more plastic waste in the state.

- Newsom vetoed a second bill to help undocumented immigrants, one that would have directed the UC and CSU systems and community colleges to hire undocumented students for campus jobs.

- Newsom vetoed a bill that would have studied reparations for families displaced at Chavez Ravine.

Wildfires and landslides

- Favorable weather conditions have helped firefighters increase the containment of three major Southern California wildfires.

- The Palos Verdes Peninsula landslide keeps getting worse as residents’ anger boils.

- Wildfires can release more energy than an atomic bomb. It’s no wonder they look apocalyptic.

Public safety and crime

- Ventura residents were evacuated from their homes — twice — as vapors wafted from the sewer.

- A pilot was killed in a midair plane collision in Lancaster.

- A motorist and a horse died in a collision on the 15 Freeway in Norco

Get unlimited access to the Los Angeles Times. Subscribe here.

Commentary and opinions

- George Skelton: Californians would love for Kamala Harris to steal this Trump idea.

- Robin Abcarian: Los Angeles school kids, get off your damn phones! Trust me, you’ll thank us later

- Patt Morrison: Where have all the orange groves gone?

- Mark Z. Barabak: Kamala Harris tried being something she wasn’t. Now that liberal makeover is dogging her candidacy.

- Paul Thornton: Southern California forests are burning. Protect them from their biggest threat — people.

- Times Editorial Board: Executions of the conceivably innocent are no better than human sacrifice.

Today’s great reads

It’s like something out of 1993 film “Homeward Bound.” A Salinas couple lost their seal point Siamese cat during a road trip in Yellowstone National Park. Benjamin and Susanne Anguiano searched for Rayne Beau (pronounced “rainbow”) for five days, with no luck. But weeks later, the feline was found in Roseville — some 800 miles west of Yellowstone — and soon reunited with his family. The Times’ Ruben Vives wrote all about Rayne Beau’s incredible trek.

Other great reads

- Funny, it isn’t hard to make a comedy show that autistic adults can enjoy too

How can we make this newsletter more useful? Send comments to [email protected].

For your downtime

Going out

- 🍕 Hungry? The Times’ Laurie Ochoa shares the perfect California road trip meal

- 🥪 The Food team tries to settle a sandwich score: What’s the best order at Langer’s?

- 🎭 The 24 Hour Plays return to Los Angeles. Writers, directors and actors write, rehearse and perform six new short plays in just 24 hours.

Staying in

- 📺 “Agatha All Along” and “The Penguin” prove that the superior universe is on television, writes critic Robert Lloyd.

- 🥗 Here’s a recipe for Malcolm Lee’s chicken curry.

- ✏️ Get our free daily crossword puzzle, sudoku, word search and arcade games.

And finally ... a great photo

Show us your favorite place in California! Send us photos you have taken of spots in California that are special — natural or human-made — and tell us why they’re important to you.

Today’s great photo is from Brian van der Brug. A great blue heron sits among a patch of invasive ludwigia along the Russian River on Aug. 13 in Forestville, Calif.

Have a great day, from the Essential California team

Ryan Fonseca, reporter

Amy Hubbard, deputy editor, Fast Break

Check our top stories, topics and the latest articles on latimes.com.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.