Los Angeles speaks Spanish, as the LéaLA literary festival is about to remind us again

- Share via

Mexico’s flood of vicious drug-related killings since the early 2000s has coarsened and corroded the country’s social fabric.

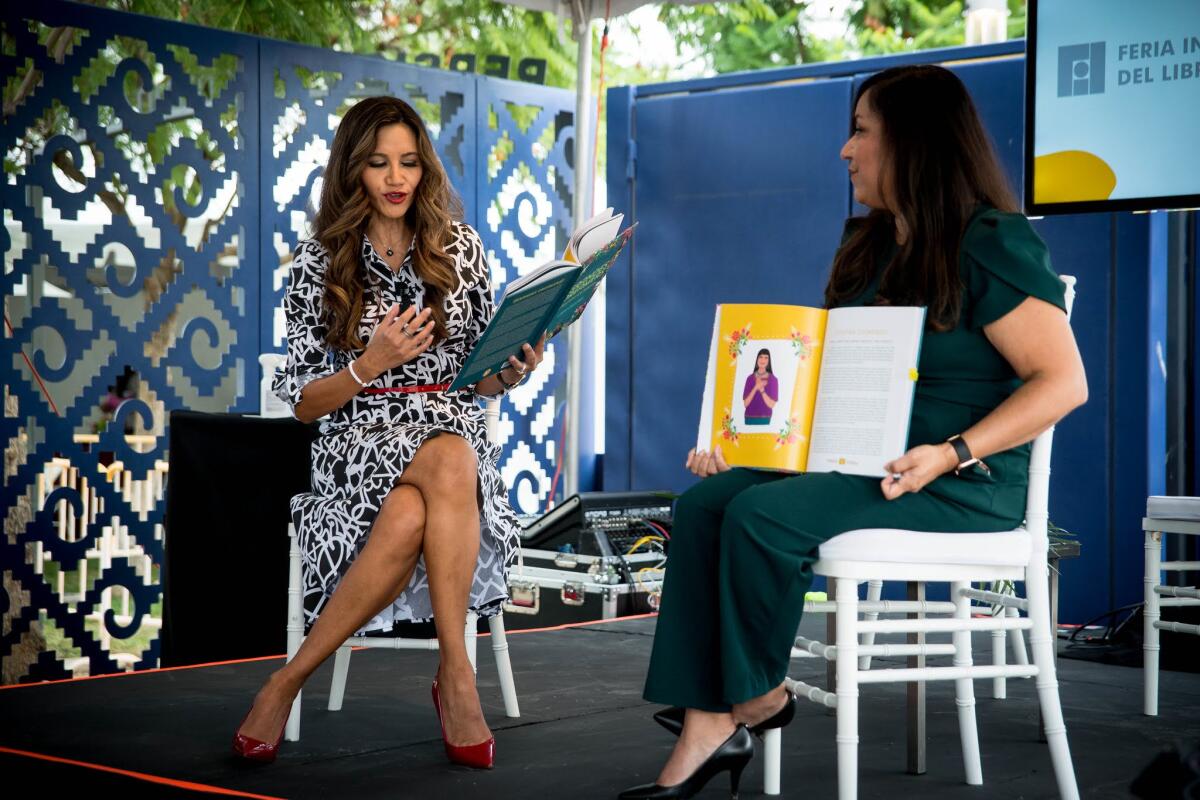

But there may be one way in which the nation’s response to that ongoing tragedy has yielded a surprising cultural boon, suggests Alma Delia Murillo, an author, screenwriter and columnist; it has fired up an energetic new generation of women writers. Murillo will be among 30 invitados at the annual Spanish-language book festival LéaLA 2023, taking place this week at LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes in downtown Los Angeles.

Over the last decade, Latin American women have gained greater visibility as both writers and publishing industry executives, Murillo says. The voices of Fernanda Melchor, Valeria Luiselli, Brenda Navarro, Dolores Reyes and other women have shaped what Murillo calls “a distinctive narrative” across a wide variety of themes, including the violence in Mexico that has “shot up to a dystopian level.” That violence is the focus of Murillo’s recent audiobook “Diez Mujeres,” its title a reference to Mexico’s grisly average of 10 femicides per day.

“It’s brutal, it’s very painful, it’s a theme that attains indignation, rage,” says Murillo, speaking in Spanish via Zoom from her home in Mexico City. “And at the same time, it’s a theme that’s so raucous that the world is looking at it. Certain nuances, included in the midst of so much violence, of so much toughness, feminine voices introduce other ways of looking, where beauty also has a place, where the tone fits well, where there is hope.”

A bookstore that’s like a favorite aunt

The slow but persistent opening of more space for Latin American female voices will be one motif of LéaLA, the largest Spanish-language literary festival in the United States. Sponsored by the University of Guadalajara, Mexico’s second-largest public higher education institute, the free, nonprofit festival launched in 2011 and drew about 36,000 attendees to its lineup of author readings, panel discussions, book signings, performances and other attractions.

By the early 2010s it had expanded to scores of authors and hundreds of trade stalls and was drawing upward of 80,000 people to the L.A. Convention Center. Interrupted twice, first in 2014 by a wobbly peso that induced a funding shortage, then by the COVID pandemic in 2020, LéaLA is returning again to Southern California in somewhat slimmed-down form.

“It’s a little bit smaller but the spirit of the festival is the same,” said Marisol Schulz Manaut, director of both LéaLA and the Guadalajara International Book Fair, the world’s largest Spanish-language literary festival.

Also unchanged is the mission of LéaLA to help serve a nearly 50% Latino city that relies on Tía Chucha’s Centro Cultural and Bookstore in Sylmar, the Libros Schmibros lending library in Boyle Heights, LA librería children’s bookstore in Mid-City and a scant supply of other venues to meet its Spanish-language reading needs.

“It’s a little strange that when there is such a strong force of spoken Spanish, we don’t encounter a correspondence in literary offerings. It’s a paradox,” said Schulz, who honed her love of English literature reading Oscar Wilde and Jane Austen.

Manaut, a top publisher who has worked with writers of the caliber of Carlos Fuentes, Mario Vargas Llosa, Arturo Pérez Reverte and Elena Poniatowska, belongs to a small but increasingly influential group of female literary entrepreneurs and industry leaders in Latin America. Starting about a decade ago, these women and female authors “little by little began to open pathways toward each other,” said Murillo, the writer.

Thousands of Angelenos descended upon the USC campus over the weekend for the 2022 L.A. Times Festival of Books. Here’s what they said about being back.

Murillo gradually abandoned her own career in fashion when she began pumping out an online blog. Other emerging women writers promoted their work on social media, eliminating the need for male gatekeepers.

“Something also was happening with female readers who began to push for and consume more of the feminine narrative,” Murillo said.

Last year, after much “resistance and persistence,” Murillo found a publisher for her first novel, “La cabeza de mi padre” (My father’s head). It centers on a woman’s mid-life road-trip reckoning with her elusive father, as well as with Pedro Páramo, the mystic patriarch who hovers over Juan Rulfo’s 1955 landmark novel of that name.

Luis Gustavo Padilla Montes, a University of Guadalajara professor and top administrator, said that L.A.’s “biculturalism and multiculturalism” makes it an attractive partner for forging additional links with Guadalajara’s institutions. He pointed to an existing collaboration between UCLA and the University of Guadalajara on programs in Spanish and Portuguese literature.

Among Guadalajara’s long-term ambitions is to open a satellite campus in Los Angeles, specifically to serve immigrant children whose parents can’t afford U.S. college tuition. More than 1 million Mexicans and Mexican Americans with roots in Guadalajara and the surrounding state of Jalisco inhabit Southern California.

Partly in recognition of the Los Angeles Unified School District’s overwhelmingly Latino and Latina student population, this year’s festival will focus on children’s literature and Mexican arte popular — handmade art. Children’s and young-adult authors will give readings and lead workshops. One, by writer Rodrigo Morlesin titled “Corazón rapero” (Rapper Heart), will guide four-person teams in composing freestyle hip-hop songs.

From a bestselling migration memoir to an acclaimed novel of suburbia, political poetry and essays and on and on, Salvadoran writers are having a big moment.

Speaking by Zoom and showing off a T shirt he bought in New York that says “If you love me, read me a book,” Morlesin said he believes his U.S. readers, especially Latin American and Asian fans, want their children to read and converse in other languages so they can absorb foreign cultures and assimilate new perspectives. He took to that path with his own children’s book “Elvis nunca se equivoca” (Elvis is never wrong), about a stray puppy wandering a menacing city while trying to evade a street gang.

Having recently published his first English-language book, “Luna Ranchera,” he’s hopeful that U.S. publishers are growing more receptive to foreign-language titles, whether in their original form or in translation.

“It’s very hard to publish Latin American books in the United States,” he said. “You have to be Gabriel García Márquez, or the winner of the Nobel Prize, to access those markets. And it’s a hardship, because the stories that are born in Latin America are rich.”

Gurba’s essays, collected in ‘Creep,’ showcase an unblinking gaze at gender-based violence and other cruelties, which the author would rather be known for.

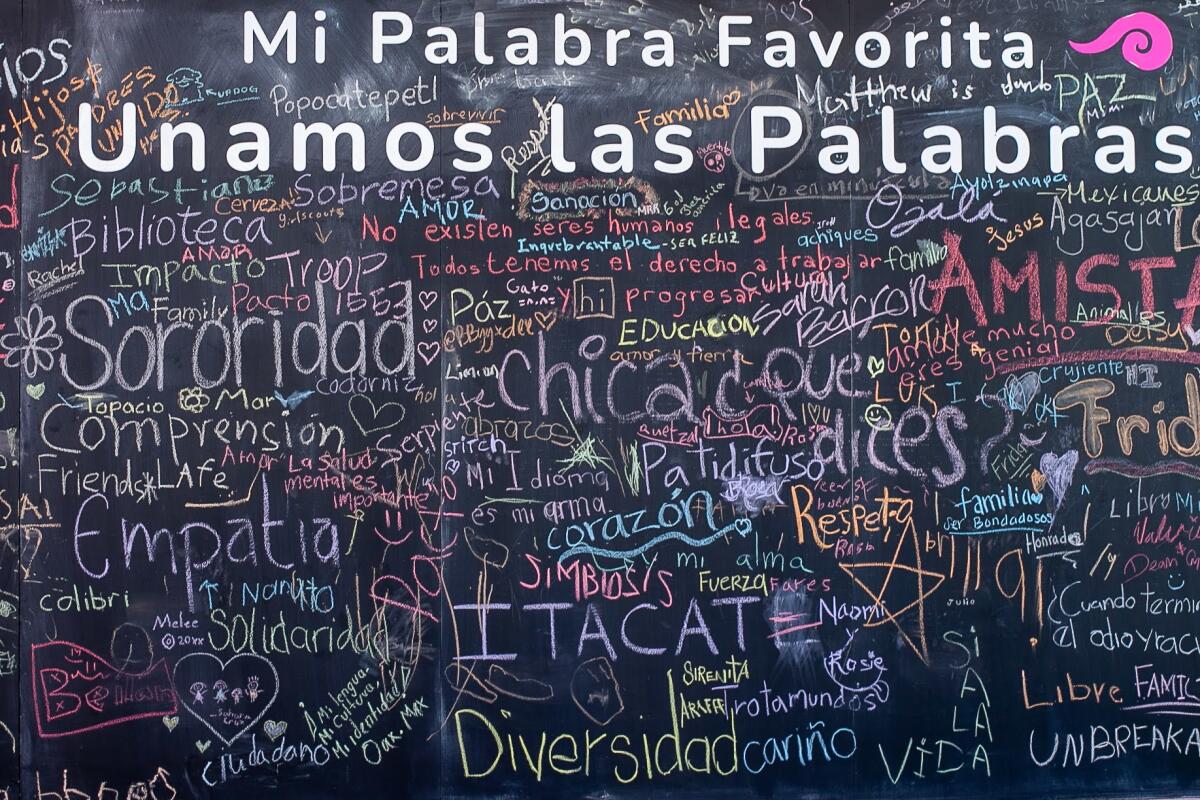

That richness includes Indigenous languages and writing, he added. The Indigenous Mixtec languages, for example, have at least 11 different words for “rain.”

“Indigenous languages are at risk not only in Mexico but all over the world. Knowing these languages isn’t a luxury. It’s a necessity.”

Morlesin related the tale of his own “bittersweet” experience as a wanderer in a strange city — Los Angeles — when at a previous LéaLA festival he witnessed the panicked aftermath of a downtown shooting.

“I was shaking when I got back to my hotel,” he recounted.

Fortunately, that story had a Hollywood ending of sorts: Fellow Mexican author Benito Taibo took him out for a hamburger, “the biggest one I’d ever seen.”

LéaLA, La Feria del Libro en Español y Festival Literario de Los Ángeles, runs Thursday through Sunday at LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes, 501 N. Main St., Los Ángeles.