Extra inventory. More sales. Lower prices. How counterfeits benefit Amazon

- Share via

Reporting from Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio — Jon Fawcett wanted to build a cellphone cable that wouldn’t fray. So he developed a charging cord wrapped in stainless steel sturdy enough to withstand an electric chainsaw.

It was a niche product that turned Fuse Chicken, Fawcett’s company of half-a-dozen employees, into a quick success. Customers raved about Fawcett’s durable designs — until he started selling them on Amazon.

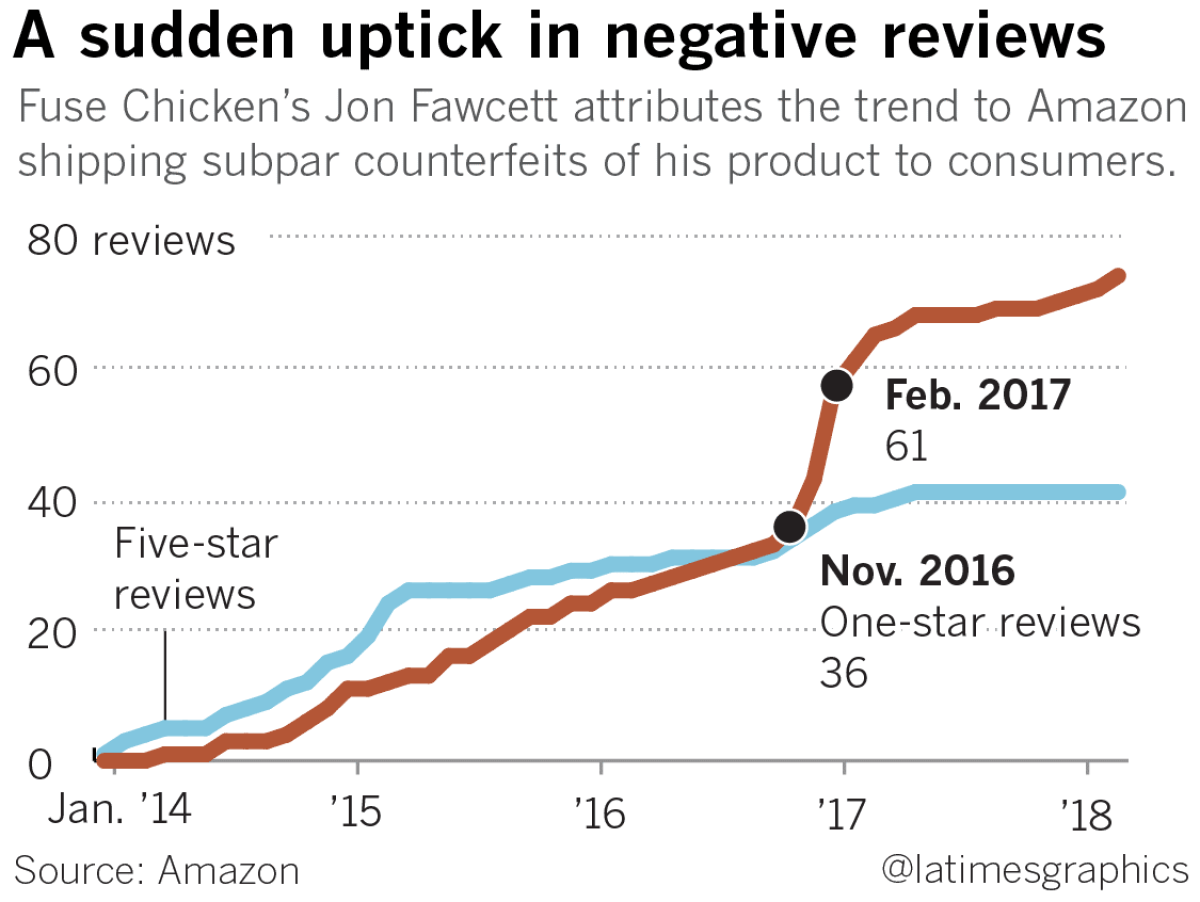

Fawcett’s customer reviews plummeted without warning. In came a deluge of one-star pans.

“Really bad quality,” read a description of an iPhone car charger in a review titled, “Broke in a week.”

Fawcett was dumbfounded. Then he found a clue in one of the reviews: a picture of a charger emblazoned with a Fuse Chicken logo that wasn’t quite right.

Over the following months, Fawcett placed numerous Amazon orders for his own merchandise. What he found would become the basis of a lawsuit he filed last year against Amazon.

Mixed in with Amazon’s inventory of authentic merchandise were crude copycats. Some looked like the real thing but didn’t include Fuse Chicken’s name. Others bore the name but weren’t made by his company, Fawcett said in an interview with The Times in his Ohio office.

His experiment suggests there is no way for even the savviest Amazon shopper to avoid the threat of counterfeits. The goods may look real online, but there is no guarantee of authenticity — whether sold by a brand, a third-party seller or Amazon’s direct-sales arm.

“That’s when I recognized how big the problem was,” said Fawcett, 43. Products were “being thrown into a single bin in Amazon’s warehouse, real and fake.”

Amazon, in court filings, denied mixing knockoff Fuse Chicken products with genuine ones. The company says it has a zero-tolerance policy when it comes to counterfeits and aggressively pursues legal action against bad actors.

Rather than come to Fawcett’s defense, Amazon plunged the small-business owner into a Kafkaesque back-and-forth that has become something of a rite of passage for those who fall victim to intellectual property infringement on the world’s biggest e-commerce site.

Pleas to audit Amazon’s inventory and remove unfair reviews were dismissed. Attempts to garner help from Amazon to learn more about the origins of the knockoff goods went nowhere.

Fawcett flooded Amazon with more goods in a desperate bid to dilute the pool of counterfeits. When an Amazon staffer eventually contacted him, it was to urge him to lower his prices to match the alternatives — products he irately pointed out were cheaper because they were fake.

“It’s gotten to that level of insanity dealing with Amazon,” said Fawcett, who estimates he lost sales in the tens of thousands of dollars but mostly fears the lasting harm of the bad reviews.

Fawcett’s Cuyahoga Falls brand, which launched after a $9,800 Kickstarter campaign, now faces a formidable opponent in court. Amazon’s outside counsel is the same high-powered Washington firm that’s represented Philip Morris, Halliburton and Huawei.

“We felt there was no choice,” Fawcett said. “We don’t have anything to hide. When you have the truth on your side it makes the bully less intimidating.”

The Amazon effect

No company has done more to legitimize online shopping than Amazon.

By offering low prices, a vast inventory and the convenience of home delivery, the technology giant helped lead a generation away from brick-and-mortar stores and normalize shopping with a click of a button.

It has made e-commerce accessible to more than a million small- and medium-sized businesses in the U.S., creating 900,000 jobs, according to Amazon. More than 20,000 small- and medium-sized businesses worldwide reached sales in excess of $1 million last year on its platform, the company said.

So ingrained is Amazon in our purchasing habits that more than half of all product searches begin on the site rather than alternatives such as Google. The world’s second-most valuable company by market capitalization behind Apple Inc. is on pace to capture half of all online sales in the U.S this year, according to research firm eMarketer.

Amazon’s market dominance gives it the power to influence the future of retail. How it handles counterfeiters could shape the behavior of the entire industry, experts say.

The sale of fake goods is at least a $461-billion global industry and expanding, in no small part because of the rise of e-commerce giants like Amazon and China’s Alibaba.

Customs agents had a fighting chance when pirated goods predominantly arrived in cargo containers. But with the rise of e-commerce, counterfeiters and their middlemen can ship goods in parcels too innumerable to catch.

“They’re like ants,” said Piotr Stryszowski, an economist for the Paris-based Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. “They’re too small for customs officers to focus on one. Yet they accumulate into a huge number.”

There’s little authorities can do apart from name and shame offenders. Alibaba’s primary platform Taobao has repeatedly been included in the United States Trade Representative’s list of “Notorious Markets” for selling counterfeits.

Then there’s Amazon. Not only has the platform avoided any serious backlash for allowing the sale of fake goods, it’s actually thrived from it, say more than two dozen brand owners, e-commerce consultants, attorneys, investigators and public policy experts.

Sellers of fake goods pay transaction and shipping fees just like legitimate businesses. But counterfeits also help Amazon’s bottom line in other ways.

The company aspires to be the store of first resort for everything, which means it needs as many brands and sellers as it can get, all offering goods at low prices. Counterfeiters help pressure brands to sell their wares on the site. Companies that avoid Amazon risk letting counterfeiters determine how their goods appear to customers on the most influential e-commerce site — ceding control, for instance, of which pictures are used to promote a product and which colors and sizes are offered.

The spread of cheaper knockoffs can also put pressure on authentic sellers and brands to lower their prices, helping Amazon win more customers.

The company has resisted calls to do more to police its site and address claims by businesses that they are losing millions in lost sales and reputational harm, according to experts.

Brands have typically shied away from suing Amazon. Courts have ruled the company isn’t liable when counterfeits are sold on its platform and that plaintiffs must instead go after the sellers of fakes. Many accept piracy as a cost of doing business.

“If you’re a small company, you have to be on Amazon,” said Jeffrey Brown, who cut the price of his $25 chilled water bowls for pets, FrostyBowlz, in half to compete with the deluge of copycats. “It’s both a huge outlet for our product and a nightmare.”

Cutting ties means losing access to hundreds of millions of Amazon customers — and it doesn’t solve the problem.

Birkenstock left Amazon two years ago after it grew exasperated with counterfeits, but the move did little to stem the flow of both real and fake versions of the company’s footwear on the platform.

Counterfeits on Amazon “enhance its market power over suppliers,” said Stacy Mitchell, co-director of the non-profit Institute for Local Self-Reliance, which has studied the impact of intellectual property infringement on small companies. “Counterfeits help Amazon, and that’s why they’re reluctant to act on them.”

Amazon disputes it benefits from counterfeits and says it has a zero-tolerance policy when it comes to fakes. It’s investing in machine-learning tools to weed out counterfeits. It offers a program called Brand Registry, which is supposed to give sellers and intellectual property owners more control of their listings. It says more than 99.9% of Amazon page views go to sellers that have never been accused of infringement. And shoppers can request refunds if they receive a knockoff.

“We strictly prohibit the sale of counterfeit products and invest heavily — both funds and company energy — to ensure our policy against the sale of such products is followed,” the company said in an e-mailed statement. “Customers trust that they will receive authentic goods when they shop on Amazon and anything that diminishes that trust is unacceptable.”

Rise of the Marketplace

Amazon’s ascendance as the world’s dominant online retailer may have been sealed when it recognized it was far more profitable to let other people sell goods than selling merchandise itself.

Amazon Marketplace, launched in 2000, allowed anyone to sign up and sell on its site. It marked a major change in strategy for the company, which was founded by Jeff Bezos in 1994 as an online bookseller.

By welcoming third-party sellers, Amazon vastly increased its inventory without a commensurate increase in its overhead needed to procure, store and ship goods.

Amazon could reap profits by charging independent sellers access to its fulfillment centers — now the backbone of its Prime subscription service, which famously offers free two-day shipping.

Combined with transaction fees, fulfillment services and advertising, Amazon can take up to half a seller’s revenue. By comparison, Amazon earns less than 5% profit margins on goods it sells directly, said Juozas Kaziukenas, founder and chief executive of Marketplace Pulse, an e-commerce analytics firm. Amazon declined to verify its profit margin.

Third-party sellers now account for more than half the goods sold on Amazon. The company’s revenue swelled to $178 billion last year, with $118.5 billion coming from product sales rather than services such as cloud computing. Amazon has recorded a profit every quarter since early 2015. Meanwhile, Bezos was recently named the richest man in modern history.

But for all the success the Marketplace has wrought, it remains one of Amazon’s biggest sources of controversy and risk. The service is often described as a messy free-for-all — a flea market run amok where up to 5 million vendors from across the world ferociously compete to sell the cheapest toothbrush or beach towel.

Here, any edge counts. Fake customer reviews are bought to boost a seller’s search results or cripple a competitor. False infringement claims are filed to temporarily shutdown a rival. And bots are programmed to undercut a seller’s price just enough to steal a position in the all-important “buy box” that goads shoppers to add items to purchase. Amazon says it’s working hard to crack down on abuse and has gone so far as to sue people responsible for fake reviews.

“People don’t see the chaos behind the listings,” said Kaziukenas, whose firm tracks tens of millions of sellers and brands online.

Amazon’s business model, he said, forced brands to compete on a global scale rather than only with rivals next to them on store shelves.

“You have millions of businesses all over the world going after you all the time,” Kaziukenas said.

That includes hundreds of thousands of sellers in China, the world’s largest producer of consumer goods, real and fake.

The risk and reward of China

For decades, even as the “Made in China” label proliferated, Chinese manufacturers earned just a small portion of sales while the lion’s share went to retailers and brands.

E-commerce changed that by giving Chinese factories and merchants direct access to the U.S., the biggest consumer economy in the world.

Amazon, which had failed to penetrate China’s tightly guarded domestic e-commerce market, instead focused on wooing Chinese exporters to fuel its Marketplace, market research firms and e-commerce consultants say.

Amazon obtained permission in 2015 to ship goods out of China, which allowed Chinese sellers to tap into Amazon’s logistical services. Of the 1 million new sellers that joined the Marketplace between 2015 and 2017, about 300,000 were from China, Kaziukenas estimates.

Enlisting legions of Chinese sellers provided the scale Amazon sought, but its drawbacks were predictable. China and Hong Kong are the origin of more than 80% of the world’s supply of fake goods, according to the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development.

It’s often difficult for U.S. brands to sue Chinese counterfeiters, who regularly falsify the contact information they provide Amazon.

To open a store, all that’s required is a business name, an address, a phone number, a government-issued ID and an international credit card.

The simplicity is by design, said Damon McCoy, a professor of computer science at New York University who has researched the role of bots in the counterfeit trade and has held meetings with Amazon on behalf of brand clients.

Any friction in signing up would stunt the Marketplace’s growth. It’s why McCoy says Amazon does little to vet sellers and their goods beforehand.

“Their stance on counterfeits is often reactive rather than proactive,” he said.

Amazon disagrees and said its software can block counterfeiters before they join the Marketplace.

“When a business registers to sell products through Amazon’s Marketplace, Amazon’s systems scan information for signals that the business might be a bad actor, and Amazon blocks identified bad actors before they can offer any products for sale,” the company said in a statement.

McCoy said if Amazon shutters one store for selling knockoffs, the owner often shifts operations to another.

“Amazon on their backend can see hundreds of other shops being paid by the same bank account, yet they don’t close them down,” McCoy said. “Instead, they just go after the one shop that was reported.”

Experts say a counterfeiter can have access to dozens, if not hundreds, of stores — often with incomprehensible names.

“I see an alphabet soup of names that looks like someone just pounded on a keyboard,” said Craig Crosby, a former LAPD investigator who founded a consumer advocacy website called the Counterfeit Report. “They’re constantly being taken down only to come back again.”

Amazon says its software can block infringers with multiple stores. The company declined to further comment on its practices, including whether it checks bank account information.

But brands say the same fraudsters keep showing up under different names — a burden for smaller companies that have to invest in hiring employees just to scan Amazon and other e-commerce sites daily for IP violators.

Experts say it’s impossible to know how many counterfeit goods are on Amazon without examining every product for sale.

Crosby, who is hired by brands to police Amazon, says his company alone has had nearly 36,000 listings removed the last two years encompassing all manner of goods, including flashlights, memory cards, iPhone cases, razor blades, cologne and even a gunsight.

“It’s a game of Whac-A-Mole,” said Corey Nielsen, maker of the Shoulder Dolly, straps used for safely lifting heavy furniture and appliances.

Nielsen, whose Colorado brand has long been targeted by fakes, says he’s not afraid of the global competition. What he can’t stand is how the Marketplace provides counterfeiters with the means to flourish.

“Amazon is not acting honorably,” Nielsen said. “I can accept a level playing field. But this is guerrilla warfare.”

‘We cannot compete’

Nielsen’s chief rival is Mark Lopreiato, owner of the Baldwin Park-based Forearm Forklift. Over the last two decades, the entrepreneurs have popularized the furniture lifting strap, which is sold by the likes of Home Depot, Walmart and U-Haul. The two competitors have formed a friendly relationship over their frustrations with Amazon.

It didn’t start out that way for Lopreiato. Amazon gave him a bigger audience than he ever could have dreamed of when he was still hustling his way through trade shows putting on demonstrations where he’d lift a refrigerator.

Lopreiato was pulling in more than $2.4 million in revenue in 2008. But only a few years later, the Marketplace was overrun by fakes priced at a fraction of the cost of Lopreiato’s $20 straps.

So brazen were Lopreiato’s counterfeiters that they copied Forearm Forklift’s marketing material, including photographs of his employees and wife lifting bulky furniture and appliances. Many fake versions were listed alongside Forearm Forklift’s promoted listings as cheaper alternatives.

Brick-and-mortar stores would complain to Lopreiato that they saw his goods cheaper online, not realizing they had seen fakes. Even teachers and parents at the school Lopreiato’s children attended said they had bought shoddy straps thinking they were genuine.

“They weren’t vetting suppliers,” said Lopreiato, 50.

By 2015, Forearm Forklift’s annual revenue had dwindled to $1.4 million. Lopreiato laid off half his employees, consolidated his seven warehouses into one and sold his bike and watch to make ends meet.

Lopreiato became one of Amazon’s most outspoken critics, detailing his plight with counterfeiters on cable TV the following year. Shortly after, Amazon sued sellers of Forearm Forklift knockoffs. Amazon won $60,000 in damages and gave it all to Lopreiato in June. He welcomed the gesture, but said its a fraction of what he’s owed given the multitude of fakes that have undermined his business.

Forearm Forklift now has a staff of 18, down from 52 at the company’s peak. Business has bounced back somewhat thanks to online sales, including on Amazon, but the company has lost a slew of distributors. Lopreiato blames it on counterfeiters, who he says have sullied his brand’s reputation and driven down prices.

“We cannot compete with people stealing our IP,” he said.

One Forearm Forklift employee’s sole job is to compile a daily list of infringers, and then instigate the often weeks-long process of having Amazon take them down. She submits an average of 100 requests a month.

Lopreiato’s office is littered with Amazon packages stuffed with copycats he’s ordered himself. Some are hard to detect, requiring knowledge of the weave and UV coating Loprieato uses. Others are more obvious, neglecting to include the black felt padding that puts less stress on the shoulders.

“There are hundreds of boxes,” Lopreiato said. “I keep thinking I’ll need them when I have my day in court.”

He knows that won’t come anytime soon. Not only is he turned off by the specter of a legal fight against the deep-pocketed giant, but he also knows Amazon has the law on its side.

How the law supports Amazon

When a YouTube or Facebook user uploads a pirated film, the companies are not at fault.

They can thank the 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act, which grants platforms safe harbor if their users infringe on copyrights. The law hinges on the premise that it would be too hard to vet everything that crosses their networks. All the platforms need to do is prove they had no prior knowledge of the objectionable content and worked quickly to remove it after being notified.

That has allowed platforms to grow exponentially, helping to give us the internet as we know it today. It has also shielded Amazon when counterfeit products are sold on its site.

In 2004, a federal court ruled that Amazon wasn’t liable for users uploading unlicensed pictures. That precedent was upheld last year when a federal appeals court affirmed the dismissal of a lawsuit brought against Amazon by a children’s pillow brand called Milo & Gabby. The husband-and-wife owners argued Amazon facilitated the sale of Chinese counterfeits; Amazon disagreed on the grounds it just provided a venue and that it was the counterfeiter who broke the law.

The judge agreed with Amazon, but not without reservations.

The “Court is troubled by its conclusion and the impact it may have on the many small retail sellers in similar circumstances to the Plaintiffs,” U.S. District Judge Ricardo S. Martinez wrote in his opinion. “There is no doubt that we now live in a time where the law lags behind technology.”

The law incentivizes willful blindness, said Kaziukenas and other experts. It’s less costly and time-consuming, they argue, for Amazon to address counterfeiters once they’ve been discovered than it is to implement a strict vetting process.

Amazon’s stance isn’t just frustrating tiny companies — it’s also irking huge tech giants.

Apple, for instance, included a number of embarrassing details about Amazon in its 2016 lawsuit against Mobile Star, a New Jersey wholesaler accused of supplying fake and dangerous counterfeits to Groupon and Amazon.

Apple said it identifies and reports thousands of infringing products on Amazon each month. During a nine-month period, the company said it purchased “well over 100 iPhone devices, Apple power products, and Lightning cables sold as genuine by sellers on Amazon.com and delivered through Amazon’s ‘Fulfillment by Amazon’ program.”

More than 90% turned out to be counterfeit.

E-mails submitted as exhibits in the case also revealed mounting frustration with Amazon’s lackluster response.

“It has now been 5 weeks since we first notified Amazon of its direct sales of counterfeit Apple products,” Apple attorney Marianne David wrote. “Amazon still has not provided any information about how it came to be selling these counterfeit Apple products directly or any of the information we requested about source, sales or remaining inventory. We are concerned that Amazon is not taking this issue seriously.”

Amazon said it has since resolved the dispute.

“In this case, we worked collaboratively to hold the vendor that provided the inauthentic goods accountable,” Amazon said in a statement.

Apple’s frustration is echoed by many brands and rights holders, who say Amazon has a penchant for dragging its feet in court and responding slowly to take down requests. Amazon denies that and says it has staff around the world working 24 hours a day, ready to take action on reports of infringement.

Publishers such as McGraw Hill and Pearson say Amazon has been too slow to provide information about more than two dozen sellers of counterfeit textbooks included in a lawsuit filed last year against the merchants, court filings show.

“Given Amazon’s well-known ability to ship goods to anywhere in the country within a single day, Amazon has no excuse for not producing the requested documents and inventory by now,” an attorney for the publishers wrote to the court in May.

Both sides declined to comment on the ongoing litigation.

A potential liability

When a product is labeled “Shipped from and sold by Amazon” it’s supposed to lend an air of authenticity.

That’s why Fawcett, of Fuse Chicken, was stunned when he discovered his counterfeits in late 2016. How could there be fakes if he was Amazon’s only known supplier for direct sales, he wondered.

Fuse Chicken’s lawsuit, now making its way through federal court in northern Ohio, represents one of the few attempts to strike Amazon where it might be legally vulnerable. Unlike with fake goods sold through the Marketplace, Amazon may not be shielded when it sells counterfeits directly.

“It’s no longer safe harbor,” Fawcett said.

Daimler AG filed a similar lawsuit last year, alleging Amazon directly sold counterfeit Mercedes hubcaps — and that it’s largely automated reporting system was woefully inadequate for addressing the scale of Amazon’s problem with fake goods.

“Amazon refuses to take reasonable steps to police intellectual property infringement or to source their ‘shipped from and sold by Amazon.com’ products only from authorized manufacturers, wholesalers and retailers,” the German automaker said in its complaint.

Amazon, in court filings, denied the allegation. The lawsuit is ongoing.

At the root of the problem, experts say, is the pressure to fulfill Prime subscribers’ two-day delivery. To do that, Amazon must have enough inventory nearby at all times.

One solution has been Amazon’s practice of lumping different sellers’ goods together in their fulfillment centers so that there’s always plenty on hand. Customers may order headphones from one seller, but actually receive headphones originating from another. The strategy works if the headphones are identical.

Co-mingling, as it’s called, is common in the Marketplace and Amazon acknowledges the practice in its answer to Fuse Chicken’s complaint. But Fuse Chicken’s suit alleges it’s also happening with inventory for Amazon’s direct sales. In e-mail correspondence with Fawcett, an Amazon official revealed there was another supplier of Fuse Chicken products for direct sales.

“It appears there was a major distributor that Amazon was buying from since their price to us was much lower than what you were offering,” Jeremiah Price, a business development manager for Amazon, wrote in November 2016.

“I’m not sure how a distributor was getting such good margins on those three products, but the system will always order from the vendor giving us the best price for the same product,” Price wrote.

Fawcett demanded Amazon stop offering Fuse Chicken products supplied by outside vendors until everything in its warehouses could be authenticated. Amazon refused.

“The moment you start getting counterfeits as significant as we did, especially when they were ‘Shipped from and sold by Amazon,’ you have to make drastic changes in how you address it,” Fawcett said. “You no longer can accept it as business as usual.”

Fawcett now laser etches each of his products with a serial number. Customers must register the serial number to be eligible for an extended warranty.

Even today, fakes keep showing up. One recent clue, Fawcett said, was when a customer input as a serial number: “Unknown.”

[email protected] | Follow me @dhpierson

UPDATES:

3:25 p.m.: This article was updated to include data from Amazon on its impact on small- and medium-sized businesses.

12:10 p.m.: This article was updated to include comment from Amazon about its use of software to block counterfeiters before they join the Marketplace.

This article was originally published at 3 a.m.