The power keeps going out at the Port of Los Angeles, raising worries about its green future

- Share via

The morning along the San Pedro docks began typically enough, summery but cool, as the first shift powered up the Port of Los Angeles. The giant cranes that fill the sky like skeletal bridges hummed to life. Semis already were lined up at the front gates, ready to take on loads of shipping containers as big as mobile homes.

But at a little past 7, an all-too-familiar trouble flared. A blip in the electric power lines so short it barely registered on the monitors of the L.A. Department of Water and Power brought major operations at the busiest seaport in the Western Hemisphere to an abrupt stop.

If the public face of the port is the forest of cranes and mountain range of cargo containers, its invisible heart is a network of computers that controls almost the entire operation. That system, along with a growing multitude of electric-powered equipment and vehicles, depends on an uninterrupted supply of electricity. Rebooting all those smart devices, sometimes requiring workers to climb to the tops of 200-foot cranes, can take several hours, no matter how brief the outage.

By the time everything was back up and running on that August morning, unloading schedules were scrambled, frustrated terminal operators struggled in vain to make up lost time and the freeway was backed up by dozens of semis.

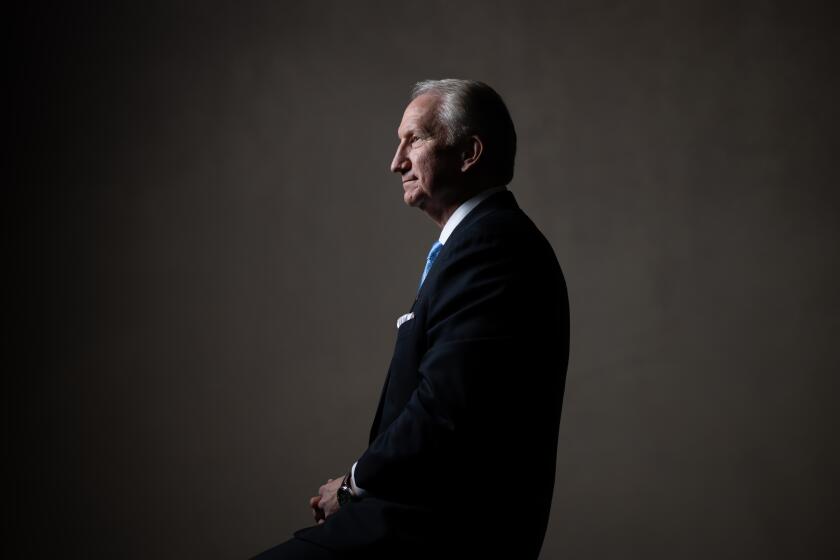

Gene Seroka says it’s a ‘generational moment’ for the Port of Los Angeles. What declining China cargo, automation, green shipping lanes and shifting political winds mean for the busiest seaport in the nation.

“It’s a significant direct financial impact,” said Jeff Vogel, general counsel to the National Assn. of Waterfront Employers, whose members include container-handling companies. “We operate in a just-in-time economic model where getting that vessel in and out of the port as quickly as possible is critical.”

And the impact of power interruptions goes beyond the immediate costs and frustration. It threatens a commitment to meet major, long-term climate change goals by further electrifying port operations and the huge distribution system it supplies.

The brief surge was one of three already this month and the 12th power-related outage of the year so far. And the recent disruptions hit particularly hard as summer is a busy season for the ports, with back-to-school and Halloween deliveries as well as retailers getting a jump on Christmas shipments. The Port of L.A. had a record July, handling more than 939,000 containers.

“It’s a pretty big deal with the amount of cargo they have to move,” said Thomas Jelenić, a vice president at the Pacific Merchant Shipping Assn., which represents the terminal operators.

It will be an even bigger deal down the road. The port, with the DWP, is aiming to phase out greenhouse gas emissions by the end of the decade.

To meet this goal, the port will need almost twice as much power as it currently uses by the end of the decade, DWP estimates. But the surges and dips have raised serious concerns about whether the port and its tenants will have reliable energy to meet their needs.

The private companies that operate container-handling terminals long ago electrified the massive ship-to-shore cranes and are now investing millions to transition forklifts, gantry cranes and yard tractors that move and stack containers, as well as other vehicles and equipment that run mostly on diesel.

“We’re up against the zero-emission mandate by 2030, and I don’t know how that happens right now,” said one terminal executive who asked not to be identified. None of the seven container terminals at the Port of L.A. would talk publicly about their grievances, saying they were concerned how municipal authorities who are their landlord and power supplier might react.

Though the Port of L.A. and its Long Beach sister facility are on the leading edge, other seaports around the country also have been moving to electrify their operations. That’s placed more demand on the grid, with occasional brownouts having been reported at some ports in the East and Gulf coasts, said the Waterfront Employers’ Vogel.

But the problem appears to be particularly acute at the Port of Los Angeles, he said.

At the Port of Long Beach, where electricity is supplied by investor-owned Southern California Edison, terminal operators say power interruptions haven’t been an issue. In fact, Sean Gamette, the port’s managing director of engineering, couldn’t recall a single outage this year.

It’s helped that Southern California Edison’s lines are mostly underground and that the port, deemed a vital infrastructure, is exempt from brownouts, an outage resulting from a temporary drop in voltage. In the mid-2000s some $180 million was invested to upgrade the electric infrastructure at the port, said Gamette.

Gene Seroka, executive director of the Port of Los Angeles, was careful not to overstate, or minimize, the disruptions and the threat to the operations. Power surges tend to affect only some of the terminals, he said, and typically everything is rebooted in a couple of hours. If you have on average one brief outage a month, that might add up to one lost shift out of 36, Seroka said.

“I don’t think it’s shutting down this port. It is not terribly impacting competitiveness.” But he added: “If I’m a terminal operator and I’ve got to pay workers for a shift that they’re not working, that’s very painful. And so we’ve got to fix it.”

The issue isn’t just financial. Outages pose safety risks, too. At one terminal yard, a power surge in mid-July caused a driverless cargo-moving truck to crash into a container. “You can have a crane operator get violently stopped and jostled,” said another terminal manager.

Terminal operators say they think the source of the outages is at the utility, and have wondered whether the DWP has even recorded the momentary outages that cause costly delays on the docks.

When COVID-19 decimated the global supply chain, it fell to Port of Los Angeles Executive Director Gene Seroka to untangle an unprecedented disruption.

DWP officials say it’s not a one-sided issue and, at the request of The Times, furnished a synopsis of the dozen outages this year. The utility said two were due to birds hitting power lines, one was caused by a truck explosion and another because a power transformer went bad.

But according to the account provided to The Times, in five outages, each lasting 10 seconds, no cause was found. Simon Zewdu, a senior manager of the DWP’s power system, said such momentary outages are usually due to an issue on the user’s side.

“Increasingly we’re seeing equipment installed by our customers that are very sensitive to minor voltage fluctuations,” he said.

Zewdu said the DWP is working to expand substations at the Port of L.A. and construct new underground lines as part of a $500-million project to be completed by 2029. These efforts should help both add power and improve reliability.

In addition, Zewdu and the Pacific Merchant Shipping Assn. began a fresh round of meetings this week to discuss strategies to mitigate outages and with an eye to their zero-emission goal. Among other things, Zewdu said he wants to install monitoring equipment on circuits on both the utility and terminal sides to discern the source of the power surges — something he said hadn’t been done yet because the terminal operators had not made a request or given permission to DWP’s power quality-monitoring team.

Jelenić, of the Pacific shipping group, said that until Monday he wasn’t even aware such a monitoring program at the DWP existed.

“Right now we’re deficient in both our near-term and long-term needs,” he said, but added that his group had a very encouraging meeting with DWP officials this week. “They were concerned about issues we’re having, they proposed solutions, and made clear, open lines of communication.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.