High interest rates are hurting people. Here’s why it’s worse for Californians

- Share via

By the numbers, the overall U.S. economy may look good, but down at the street level the view is a lot grimmer and grittier.

The surge in interest rates imposed by the Federal Reserve to slow inflation has closed like an acrid cloud over would-be homeowners, car buyers, growing families, and businesses new and old, large and small. It has meant missing opportunities, settling for less — and waiting and waiting and waiting.

It’s not that the average American is underwater. It’s that many feel that they’re struggling more than they anticipated and feel more constricted. In the American Dream, if you work hard, things are supposed to get better. Fairly or not, that may be a big part of why so many voters have expressed unhappiness with President Biden’s handling of the economy.

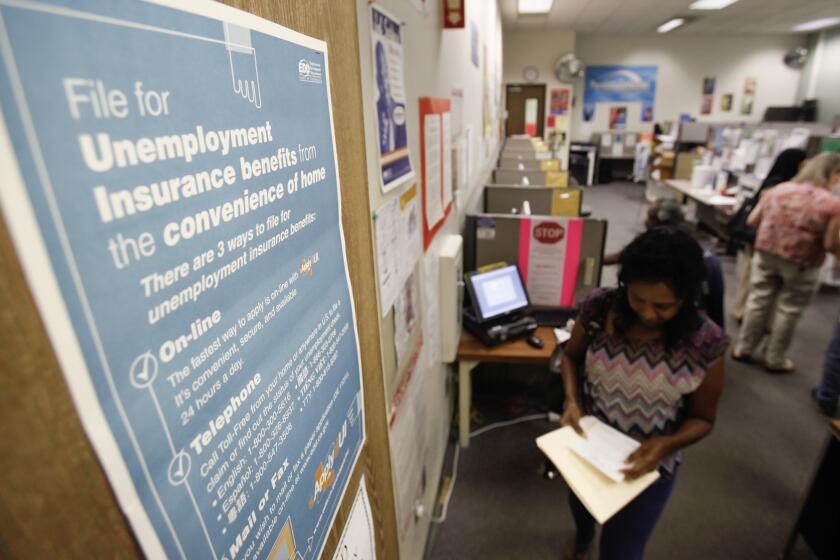

In a surprisingly strong economic report, California employers stepped up hiring in May and the state unemployment rate fell for the first time since 2022.

The cost of borrowing, whether for mortgages, credit cards or car loans, is the highest in more than two decades. And that is weighing especially hard on people in California, where housing, gas and many other things are more expensive than in most other states.

California’s economy also relies more on interest-rate-sensitive sectors such as real estate and high tech, which helps explain why the state has been lagging in job growth and its unemployment rate is the highest in the nation.

Harder to budget

When interest rates rise, savers can earn more on their deposits. But in America’s consumer society, for most people higher rates mean that a lot of things cost a little (or a lot) more. That makes it harder to stretch an individual or family budget. It may mean giving up on the nicer car you had your heart set on, or settling for a smaller house, or a shorter, less glamorous vacation.

And with every uptick in interest rates, which is almost inevitably passed on to customers, some have had to give up on a purchase entirely.

Geovanny Panchame, a creative director at an advertising agency, knows these feelings all too well: He thinks often about what could have been if he and his wife had bought the starter home they were planning for in 2020.

Back then, they had been pre-approved at an interest rate of 3.1% — right around the national average — but were outbid several times. They figured they’d wait a few years to save more money for a nicer place.

Four years later, the couple are still renting an apartment in Culver City — and now they’re expecting their first child.

Pushing to buy a house and get settled before their son is born in December, they recently made an $885,000 offer for a three-bedroom, 1.5-bath home in Inglewood. They plan to put down 10%. At the current average mortgage interest rate of 7%, that would mean a monthly payment of about $5,300 — $1,900 more than if they had an interest rate of 3.1%.

The economy has shown some signs of cooling, though job growth remains strong and average wage gains are running slightly above the rate of inflation.

The source of that increase is the Federal Reserve’s power to set basic interest rates, which determines the interest rates for almost everything else in the economy. The Fed’s benchmark rate went up rapidly, from near zero in early 2022 to a generational high of about 5.5%, where it has been for almost a year. The rate has been higher in the past, but after two decades in which it was mostly at rock bottom, most people had gotten used to both very low inflation and low interest rates.

“Clearly, we look back and we probably should have kept going and hopped into something,” Panchame, 39, said. “I’ve been really sacrificing a lot to get to this point to purchase a home and now I just feel like I got here but I didn’t work quick enough because interest rates have gotten the better of me.”

Add property taxes and home insurance, and it’s even more painful for home buyers because those costs have also risen sharply since the COVID-19 pandemic, along with housing prices themselves.

A typical buyer of a mid-tier home in California, priced at about $785,000 in the spring, was looking at a total housing payment of about $5,900 a month. That’s up from $3,250 in March of 2020 and almost $4,600 in March of 2022, when the Fed began raising interest rates, according to the California Legislative Analyst’s Office.

It wasn’t supposed to work like that: Lifting interest rates as fast and as high as the Fed did, in its effort to curb inflation, should have led to falling home prices.

But that didn’t happen, mainly because relatively few homes came on the market. Most existing homeowners had locked in lower mortgage rates before the surge; selling those houses once interest rates took off would have meant paying higher prices and interest rates on other homes, or bloated rents for apartments.

For most homeowners sitting on the low rates of the past, their financial well-being was further supported by low unemployment and incomes that generally remained on par with inflation or grew a little faster. And many had cushions of savings built up in early phases of the pandemic, thanks partly to government support.

Stubbornly high inflation and interest rates are taking an increasing toll in California. New data show that millennials are feeling the pinch hardest of all.

All of which has kept the U.S. economy as a whole humming along, blunting the full effects of higher interest rates.

“Consumers are doing their job,” said Claire Li, senior analyst at Moody’s Investors Service, though she added that there are now signs of slower spending, evidenced by consumers cutting back on credit card purchases.

Unlike most home loans, credit card interest rates aren’t fixed. And today the average rate has bounced up to almost 22% from 14.6% in 2021, according to Fed data. That’s starting to squeeze more borrowers, adding to their unease.

Rising credit card debt

In California, the 30-day delinquency rate on credit cards is nearing 5% — something not seen since late 2009 around the end of the Great Recession, according to the California Policy Lab at UC Berkeley.

Lower-income and younger borrowers are more prone to falling behind on credit card, auto and other consumer loan payments than those with higher incomes. And it’s these groups that are feeling the effects of higher interest rates the most.

Christian Shorter, a self-employed tech serviceman who lives in Chino, just bought a used Volkswagen Jetta for $21,000. He put down $3,500 and financed the rest over 69 months at an annual interest rate of 24%. His monthly payment is more than $480, and by the end of the loan he will have paid about $15,000 in interest.

Shorter, 45, said he doesn’t have good credit. He plans to take out a personal loan when interest rates drop and pay off the car debt. “Definitely, definitely, they should lower interest rates,” he said of the Fed.

Between the jump in interest rates and prices of new vehicles, some auto buyers have downgraded to cheaper models. The biggest shift, though, especially in California, has been a move by more buyers to turn to electric vehicles to save on fuel costs, says Joseph Yoon, a consumer analyst at Edmunds, the car research and information firm in Santa Monica.

In May, he said, buyers on average financed about $41,000 on a new vehicle purchase at an interest rate of 7.3% (compared with 4.1% in December 2021). Over 69 months, that translates to a monthly payment of $745.

“For a big part of the population, they’re looking at this car market and saying, ‘I got to wait for something to break,’ like interest rates or dealer incentives,” Yoon said.

For a lot of small-business owners, who drive much of the economy in Los Angeles, they don’t have the luxury of waiting it out. They need funds to survive, or to expand when things are going well.

But many can’t qualify with traditional commercial lenders, and when they can they’re typically looking at interest rates of 9%; that’s more than double what they were before the Fed’s rate hikes, according to surveys by the National Federation of Independent Business.

One result: More and more people in Southern California are looking for help from lenders such as Los Angeles-based Lendistry, one of the nation’s largest minority-led community development financial institutions.

From January to May, applications were up 21% and the dollar volume of loans rose 33% compared with a year earlier, said Everett Sands, Lendistry’s chief executive. Interest rates on his loans range from 7.5% to 14.5%.

“Business owners, they’re resilient, entrepreneurial, scrappy — they’ll figure out a way,” he said, adding that he sees many doing side jobs like driving for Uber or making Instacart deliveries at night.

Even so, Sands said, the higher borrowing costs inevitably mean less money spent on things like investing in new technology and software and bringing on additional staff, as well as delays in owners growing their businesses.

“Some of them lose out in progressing forward.”

‘When you put everything on the line, you get desperate.’

— Jurni Rayne, Gritz N Wafflez

Jurni Rayne, 42, started her brunch business, Gritz N Wafflez, as a ghost kitchen in February 2022, preparing food orders for delivery services. She financed that by maxing out her credit cards and getting a merchant cash advance, which is like a payday loan with super high interest rates. Her debts reached $70,000.

“When you put everything on the line, you get desperate,” said Rayne, a Dallas native who moved to Los Angeles a decade ago and has worked as a manager at California Pizza Kitchen and the Cheesecake Factory. “You don’t care about the interest rate, because it’s something like between passion and insanity.”

She has since paid off all the merchant loans. And her business has seen such strong growth that last year Rayne got out of the ghost kitchen and into a small spot in Pico-Union, starting with just three tables. She now has 17 tables and a staff of 14.

This fall she’ll be moving to a bigger location in Koreatown and has her sights on a second restaurant in South Los Angeles. But she frets that she could have expanded sooner if interest rates had been lower and she’d had more access to financing.

Economists call that an opportunity cost. For Rayne, it’s personal.

“Absolutely, lower interest rates would have helped me,” she said.

For many others, the wait for lower rates continues without the balm of intermediate success.

Lynn Miller, 60, began looking to buy a home in Orange County about a year ago, hoping to upgrade from her current 1,600-square-foot apartment.

“It’s not bad, it’s just not mine — the dishwasher is crappy, the washing machine is old,” she said of her rental in Corona del Mar. “I’m obviously not going to invest in these appliances. It’s just different not owning your own home.”

It’s been a discouraging process, she said, especially when she inputs her numbers into the mortgage calculators on Zillow and Realtor.com, which churn out estimates based on current interest rates.

“If you look at those monthly payment numbers, it’s shocking,” Miller, a marketing consultant, said. “It’ll get better, but it’s just not better right now.”

She’s continuing her house search — she’d love to buy a single-family, three-bedroom home with a backyard for a dog — but is holding off for now.

“I’m still waiting because I do think that interest rates are going to go down,” Miller said, although she knows it’s a guessing game. “I could end up waiting a long time.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.