Independent booksellers continued to expand in 2023 even amid slow industry sales

- Share via

NEW YORK — Three years ago, Erin Decker was a middle school librarian in Kissimmee, Fla., increasingly frustrated by the state’s book bans and worried that she couldn’t make a difference remaining in her job.

So, she and fellow librarian Tania Galiñanes thought of a way to fight back.

“We just put our heads together and decided a bookstore would help make sure students could get to books that were being pulled from shelves,” says Decker, whose White Rose Books & More opened last fall in Kissimmee. The store is named for a resistance group in Nazi Germany and features a section — ringed by yellow “caution” tape — dedicated to such banned works as Maia Kobabe’s “Gender Queer,” Jonathan Evison’s “Lawn Boy” and John Green’s “Looking for Alaska.”

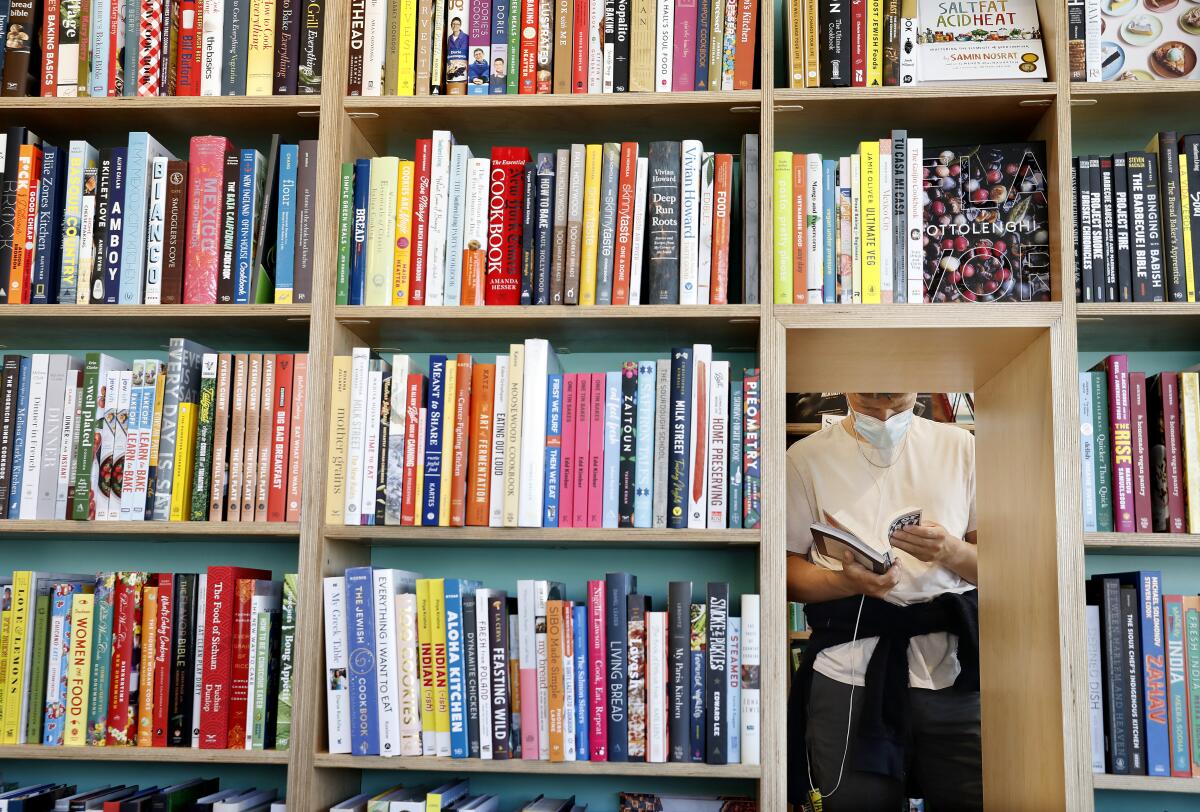

White Rose Books is part of the ever-expanding and diversifying world of independent bookstores. Even as industry sales were slow in 2023, membership in the American Booksellers Assn. continued its years-long revival. It now stands at 2,433, more than 200 over the previous year and nearly double since 2016. About 190 additional stores are in the process of opening over the next two years, according to the ABA.

“Our numbers are really strong, and we have a solid, diverse pipeline of new stores to come,” says the book association’s chief executive, Allison Hill. She cites a variety of reasons for people opening stores, from opposing bans to championing diversity to pursuing new careers after the pandemic.

“Some are opening to give back to their community. And some still just love books,” she says.

Recent members include the romance-oriented That’s What She Read in Mount Ayr, Iowa; Seven Stories in Shawnee, Kan., managed by 15-year-old Halley Vincent; and more than 20 Black-owned shops.

In Pasadena, Octavia’s Bookshelf is named for the late Black science fiction author Octavia Butler and bills itself as “a space to find community, enjoy a cup of coffee, read, relax, find unique and specially curated products from artisans from around the world and in our neighborhood.”

Leah Johnson, author of the prize-winning young adult novel “You Should See Me in a Crown,” was troubled by the surge in book bans and by what she saw as a shortage of outlets for diverse voices. Last year, she founded Loudmouth Books, one of several independent sellers to open in Indianapolis.

“I’m not a person who dreamed of opening a bookstore. I didn’t want to be anybody’s boss,” Johnson says. “But I saw a need and I had to fill it.”

Most of the new businesses are traditional “brick and mortar” retailers. But a “bookstore” can also mean a “pop-up” business like Loc’d & Lit, which has a mission to bring “the joy of reading to the Bronx,” the New York City borough that had been viewed by the industry as a “desert” for its scarcity of bookstores. Other new stores are online only, among them the Be More Literature Children’s Bookshop and the used books seller Liberation Is Lit.

Nick Pavlidis, a publisher, ghost writer and trainer of ghost writers, launched the online Beantown Books in 2023 and has since opened a small physical store in suburban Boston.

“My goal is to move into a larger space and create a friendly place for authors to host events,” he says, adding that he’d like to eventually own several stores.

Independent bookselling has never been dependably profitable, and Hill notes various concerns — rising costs, dwindling aid from the pandemic and the ongoing force of Amazon.com, which remains the industry’s dominant retailer even after the e-book market stalled a decade ago. Last month, the booksellers association filed a motion with the Federal Trade Commission, seeking to join the antitrust suit against Amazon that the FTC announced in 2023. The motion states in part that Amazon is able to offer prices “that ABA members cannot match except by forgoing a sustainable margin, or incurring a loss.”

Just opening a store requires initiative and a willingness to take risks. Decker says that she and Galiñanes had to use retirement money because lenders wouldn’t provide credit until they were actually in business. The owner of Octavia’s Bookshelf, Nikki High, is a former communications director for Trader Joe’s who relied on crowdfunding and her own savings to get her store started.

“Even with tons of planning, and asking questions and running numbers, it’s been very difficult,” High says. “I don’t know that I could have prepared myself for what a shrewd businessperson you have to be to make a living out of this.”

High cites a variety of challenges and adjustments — convincing customers they don’t have to order items from Amazon.com, supplementing sales by offering tote bags and journals and other nonbook items. Knowing which books to stock has also proved an education.

“I would read a book and think it’s the best thing ever and order a bunch of copies, and everybody else is like, ‘No, I don’t want that book,’” she explains. “And when we started, I wanted to be everything for everybody. We had a ton of different categories. But I found out that short stories and poetry almost never sell for us. People want general fiction, bestsellers, children’s books. Classics sell very well, books by James Baldwin and Toni Morrison and bell hooks and June Jordan.”

“It’s incredibly important to listen to your customers.”

Italie writes for the Associated Press.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.