Column: American unions have finally remembered how to win

- Share via

More than 30 years ago, Chicago labor lawyer Thomas Geoghegan penned what he thought was an obituary for organized labor.

His classic 1991 book was titled “Which Side Are You On?: Trying to Be For Labor When It’s Flat on its Back.”

The book’s first words were these: “Dumb, stupid organized labor: this is my cause. But too old, too arthritic, to be a cause. ... Labor gives off now an almost animal sense of weakness.”

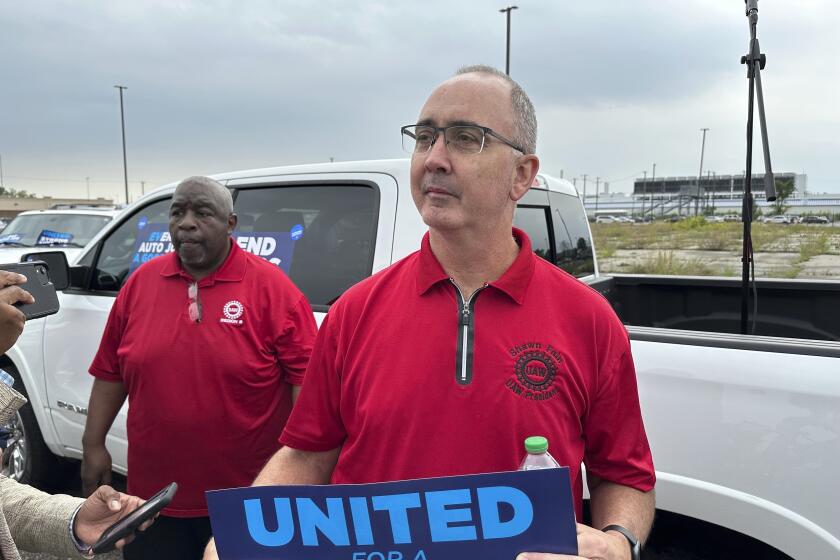

One of our biggest goals is to organize like we’ve never organized before. When we return to the bargaining table in 2028, it won’t just be with the Big Three. It will be the Big Five or Big Six.

— UAW President Shawn Fain

When Geoghegan wrote that, only 16% of the workforce was unionized. “Once it drops to 10, it might as well keep dropping to zero,” he wrote.

At the end of 2022, the overall rate was 10.1% — and kept that high only because of the 33% membership rate of public-sector workers. In the private sector, the rate is 6%.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Yet in recent months, the U.S. labor movement has shown an amazing surge of strength, demonstrated by the truly impressive contracts the United Auto Workers reached over the last week with the Big Three automakers; the contract with General Motors announced Monday follows deals with Stellantis (the owner of Chrysler) and Ford.

The contracts are tentative, pending ratification by the members, and the Stellantis and GM contracts haven’t been fully disclosed. But it’s presumed that they follow the Ford deal, which has been published.

The Ford provisions include raises totaling at least 25% and potentially as high as 33% over the four-year life of the contract; the end of the detested two-tier wage rates that shortchanged new employees and eroded union solidarity; the restoration of annual cost-of-living increases, which the union gave up in 2009 to help the companies through the recession; and a guarantee of job security as the company transitions to electric vehicle manufacture.

Ford also committed to $8.1 billion in plant investments over the next four years, including at least $430 million at EV plants.

The auto contracts follow some other notable victories this year. Hollywood writers ratified a new contract with studios Oct. 9 after a nearly five-month strike, securing improved pay and staffing on TV series, better residual payments for streaming, and protections against the use of artificial intelligence. Negotiations between the studios and the Screen Actors Guild are continuing.

As usual, the media and politicians are blaming the possibility of an auto strike on the auto workers union, but company managements are the guilty parties.

UPS reached a contract agreement with 330,000 Teamster-represented drivers and other package handlers in July, staving off a strike that could have crippled its business and reverberated across the U.S. economy.

Political commentators are likely to paint the end of the UAW strike as a relief for President Biden, on the grounds that unresolved labor unrest would be a drag on his reelection prospect. But the contract gains warrant a more positive spin.

They might not have been possible, argues Robert Kuttner at the American Prospect, had not the federal government responded to a history of corruption at the top of the union by reaching a consent decree last year that required the direct election of top officers by the membership. “It was this victory for union democracy that allowed the rank-and-file reform caucus called United All Workers to elect a slate of officers led by the militant Fain,” Kuttner wrote. Shawn Fain was elected president of UAW in March.

Biden offered foursquare support for the union, taking the unprecedented step for a sitting president of walking the picket line with them at a GM factory in Michigan in September. “You guys, the UAW — you saved the automobile industry back in 2008 and before. You made a lot of sacrifices. You gave up a lot. And the companies were in trouble. But now they’re doing incredibly well. And guess what? You should be doing incredibly well too. It’s a simple proposition. Folks, stick with it.”

Biden’s effort may tell workers where their political interests lie. “The labor movement will be back when workers realize — from the UAW deals, most lately — that their future is with a left led by people like Shawn Fain,” Geoghegan told me by email. “Maybe it will show them how stupid it is to keep voting for Trump.”

The UAW’s deals with the automakers offer a few lessons about labor negotiations. One is that you should always be wary of taking as gospel management’s claims about the devastating effect on their survival of paying workers more.

Column: It’s a happy Labor Day indeed after NLRB cracks down on employer sabotage of union elections

After nearly 30 years, the National Labor Relations Board restores a policy that truly punishes employers for unfair labor practices.

The automakers painted the UAW’s contract offers as almost existential threats. This was manifestly an exaggeration at best. No one expected the UAW to get everything it sought — it started at 46% raises over four years and settled for 33%, which is very good; GM and Ford started at 9% and Stellantis at 14.5%.

But as labor historian Eric Loomis observed after the Ford win, “Any argument that the other companies can’t afford it is hard to take seriously when Ford cut the deal.”

In fact, GM and Stellantis notched combined profits of $25.7 billion last year (Ford booked a nearly $2-billion loss, largely from writing down its investments in EV and autonomous vehicle companies). The Big Three reported combined profits of about $20 billion in the first half of this year, which ended June 30.

The three have been generous in passing profits on to shareholders through stock buybacks. GM has repurchased more than $3 billion in shares since mid-2022 and issued dividends to shareholders of $397 million last year. Just seven days ago the company declared a quarterly dividend of 9 cents a share, at an estimated cost of $123.5 million.

Ford made buybacks of nearly $500 million and paid dividends of about $2 billion last year, and Stellantis paid out about $4.36 billion to shareholders last year and has announced a $1.6-billion buyback program for this year.

Another is that labor negotiations, when they’re conducted in good faith, should be seen as a potential win-win. Better pay for workers cuts down on absenteeism and turnover, which is a phenomenon that the original Henry Ford, by no means an outright friend of labor, perceived in 1914.

It’s possible that his successors were planning to invest $8.1 billion in their manufacturing plants anyway, but writing it into the contract gives the union a win and ensures that the workers will be on hand to run the machines that money will buy.

The counter-examples are Starbucks and Amazon, which treat union organizers and members as disease-carrying threats. Has that quashed organizing efforts at those companies? To ask the question is to answer it.

Then there’s the question of strategy. Fain scrapped the union’s traditional approach of selecting one of the Big Three to negotiate with, then using that contract as a template for the others.

Republicans are bowing to industry lobbyist in loosening state child labor laws. The inevitable result will be a rise in child deaths in the workplace.

Instead, he conducted contract talks with all three simultaneously and dialed up the heat over time by striking selected plants, starting with minor manufacturing facilities and moving up to crucial plants as talks dragged on. Before Stellantis and Ford settled, 45,000 autoworkers had walked out.

At GM, 18,000 workers were off the job; the latest plant to be shut down, over this weekend, was its Spring Hill, Tenn., factory, its largest plant in North America, where 3,900 workers make Cadillacs and GMC SUVs.

Fain’s goal was to inflict incrementally greater pain, until the cost of shuttered factories exceeded that of a contract. Ford had said that it incurred $1.3 billion in costs from its walkouts. GM had estimated its costs at $800 million, with the prospect of $200 million a week in further losses until the strike settled.

One lesson that union leaders seem to have absorbed in recent years is that contract gains are the key to organizing more facilities and recruiting new members. After the Teamsters emerged victorious from a two-week strike at UPS in 1997, AFL-CIO President John Sweeney delivered that message to his members.

“You could make a million house calls, run a thousand television commercials, stage a hundred strawberry rallies, and still not come close to doing what the UPS strike did for organizing,” he told the union’s national convention after the strike ended.

Indeed, Fain told members during a talk streamed over Facebook on Sunday that he intends to place the UAW’s latest victories at the center of a new organizing drive focused on nonunion manufacturing plants owned by overseas carmakers such as Toyota and BMW. “One of our biggest goals,” he said, “is to organize like we’ve never organized before. When we return to the bargaining table in 2028, it won’t just be with the Big Three. It will be the Big Five or Big Six.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.