(Sean Dong / For The Times)

- Share via

VISTA, Calif. — Officially, there are 18 ways to use Dr. Bronner’s Magic Soaps: The same amber liquid you rub on your body doubles as a toothpaste, a fruit and vegetable rinse, a decongestant, a laundry and dishwashing detergent, a shaving cream substitute, a floor-mopping solution, a shampoo for you or your dog, and a toilet bowl cleaner.

In the company’s earlier days, its eccentric founder crammed even more suggested applications onto the text-heavy, world peace-espousing labels that have become a hallmark of the cult brand. The multitasking soap, Emanuel Bronner promised, could kill fleas and ticks — until the Environmental Protection Agency made him change the language (he amended it to “cleans fleas and ticks”; today’s updated version says “ant spray!”).

There was also Dr. Bronner’s — he wasn’t actually a doctor — assertion that the product, made primarily of water and plant oils, could prevent pregnancy.

“I think my grandfather was going off of, if you change the pH of the environment, a fertilized egg would be unviable — so if you wash with the soap after intercourse, then it would functionally act as birth control,” said Lisa Bronner. “That wasn’t the road that we wanted to go down.” (The family-owned company backed away from the claim after its founder died in 1997.)

Perhaps inspired by that experimental ethos, customers have discovered their own unusual uses in the years since Emanuel started mixing gallons of peppermint castile soap out of his Pershing Square tenement apartment in 1948.

The result was so good that what had begun as a way for the third-generation soap maker to propagate his spiritual message — by printing it onto the labels of the bottles in dense blocks of tiny script — became the top-selling natural soap brand in the country, with deep footholds among hippies, campers, backpackers, vegans, hikers, moms, gardeners and other niche groups.

“It’s the official soap of the American ferret owners association,” grandson Mike Bronner said at a recent natural products trade show in Anaheim, a wall plastered with 10-foot-tall images of candy-colored Dr. Bronner’s bottles looming over him. “I didn’t even know people owned ferrets.”

“Whatever your subculture is,” added older brother David Bronner, “we’re your soap.”

From the company’s booth nearby, cheerful Dr. Bronner’s employees were doling out samples, rainbow bumper stickers and the brand’s newest organic vegan chocolate bar flavor — cool peppermint cream, a nod to its original soap scent. Also up for grabs: copies of Emanuel Bronner’s 70-page screed, titled “The Moral ABC,” and vinyl records of him reciting it.

Like the soap labels, the wrappers on Dr. Bronner’s Magic All-One Chocolate are crowded with exclamation-point-studded passages from “The Moral ABC,” which details in rambling, often incoherent prose Emanuel’s belief that all beings are interconnected and must join together regardless of religious or ethnic divides. “All-one or none!” he liked to shout in what would become the company’s motto. (It does not, as many have assumed, refer to the soap’s reputed all-purpose properties.)

David, Mike and Lisa Bronner grew up in Glendale, not giving much thought to the prospect of one day taking over the family business and generally regarding their grandfather as a bewildering figure.

“My granddad was always talking about uniting ‘Spaceship Earth,’ and it was kind of sailing over our heads,” David said.

“He’d be talking to us as if we were all PhD students in religious studies,” Mike said of visits to Emanuel’s home when the siblings were in elementary school. “He was blind, and every once in a while he would say, ‘Are you there?’ and we’d be like, “All-one, Grandpa!’ And he’d be like, ‘Very good. OK, I want you to recite the peppermint bottle.’”

Today, David and Mike run Dr. Bronner’s as equal partners, carrying on the brotherly love philosophy of their late grandfather while growing the 75-year-old company to $170.3 million in annual revenue last year. Revenue totaled $4 million in 1998, the year their father, Jim Bronner, died; a decade before, he had saved the flailing company from bankruptcy.

Dr. Bronner’s soap, initially rooted in counterculture and relegated to the shelves of health food stores, is now sold at major U.S. retailers and in 40 countries, with a bottle or bar sold every 0.95 of a second. At $16.99 for a one-quart bottle, it’s prized for being intensely fragrant, eco-friendly, biodegradable, fair-trade, gentle on the skin and cost-effective due to its super-concentrated formulation (“Dilute! Dilute! OK!” the labels urge).

Sandra Bullock once shared her window-washing method using Dr. Bronner’s almond-scented soap. Kristen Bell said the tingly peppermint “is nice for a foot soak at the end of the day.” Drew Barrymore called it “the miracle natural product,” and Lady Gaga was photographed in a bathtub with a green bottle of Dr. Bronner’s visible on the ledge. (None is a paid spokesperson.)

Elite grocery chain Erewhon is embarking on an aggressive expansion in Southern California. Started as a humble bulk grains outlet, its cult success is rewriting the rules of the supermarket business.

“More and more mainstream folks are grooving on us,” said David, 50, a Harvard graduate with a degree in biology and a penchant for saying, “Right on.”

Although Dr. Bronner’s has gained widespread popularity, the company — legally registered as All-One God Faith Inc. — is no conventional corporate giant. One of its core “cosmic principles,” it says, is to “fund and fight for what’s right!”

Dr. Bronner’s progressive ideals are largely driven by tie-dye- and black-fedora-wearing David, who is CEO, but not chief executive. The three letters instead stand for “cosmic engagement officer.” Mike is president, and the tonal difference in their titles loosely reflects the contrast in their personalities. Lisa, the youngest, is consumer educator and blogger; their mother, Trudy Bronner, is chief financial officer; and Lisa’s husband, Michael Milam, is chief operating officer.

We take stands that aren’t popular with everybody. People say, ‘Why don’t you just make soap?’

— David Bronner, Dr. Bronner’s CEO

When we meet at the natural products expo, David — fresh off a vision quest in Mexico in which he’d had no food or water for four days — shared that an LSD- and ecstasy-fueled trip at a gay trance club in his 20s helped him finally understand his grandfather. It was an awakening of “divine love and light” that continues to shape how he leads Dr. Bronner’s.

“He definitely fell short in some ways,” David said a few weeks later during a tour of the company’s headquarters and soap factory in Vista. “But in other ways, was this mystically tapped-in genius that was doing the best he could to help the world.”

Born in 1908 to a family of Jewish German soap makers, Emanuel Heilbronner — he dropped the “Heil” after the rise of Hitler — immigrated to the U.S. when he was 21. His parents stayed in Germany and were killed in Nazi concentration camps during the Holocaust.

Emanuel, then living in Chicago, made it his personal mission to heal the fractured world, and began delivering fiery public lectures to anyone who would listen. According to family lore, his sister had him committed to a mental health facility in Elgin, Ill., where he received electric shock treatments that he believed permanently damaged his eyesight. He escaped in 1946 and made his way west to Las Vegas; a lucky spin of the roulette wheel won him enough money to get to Los Angeles.

There, Emanuel took up his soapbox once more, before the runaway success of his soap overshadowed his proselytizing. But spreading his ideology remained an all-consuming obsession, making him by all accounts a neglectful father who ultimately placed his three children in foster care.

“My father kind of thought of ‘The Moral ABC’ that was on the label as ... what took his dad away from being a dad,” Mike said.

A 2007 Los Angeles Times story described Emanuel as “a bizarre character of epic proportions.” In an article two decades earlier, the paper noted that “the elder Bronner spends much of his time chanting, speaking and ranting infinite variations of the Moral ABC into a dozen or more tape recorders placed strategically around the house. A human audience — whether it’s his son, a secretary or a reporter — is little more than another tape recorder.”

Over time, the family has come to terms with its tumultuous history, embracing the inspirational aspects of its complicated patriarch while learning to make peace with the rest.

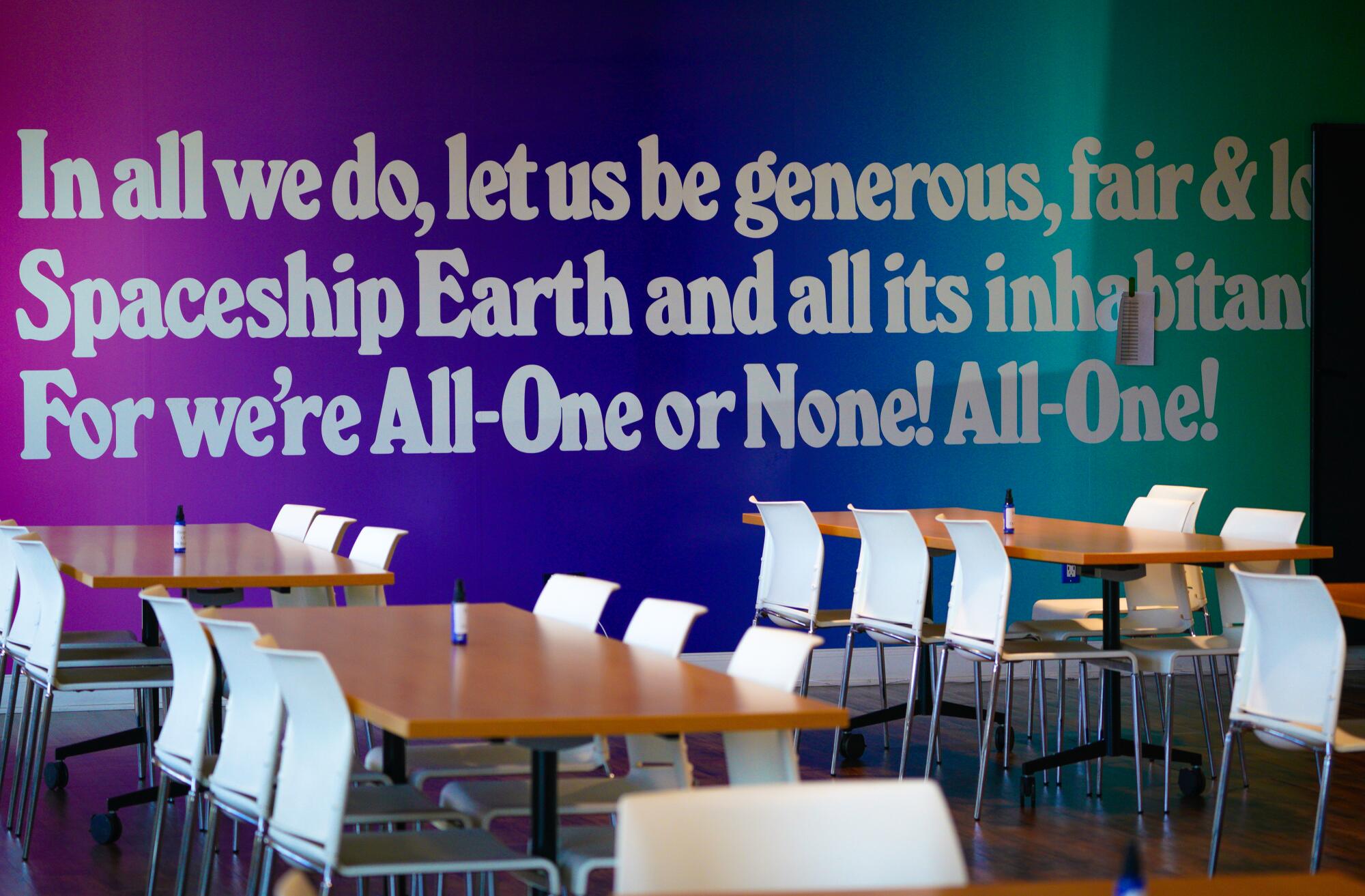

Emanuel’s lasting influence can be found throughout the company’s headquarters in Vista, where Dr. Bronner’s relocated in 2015 after outgrowing its home in nearby Escondido: in an enormous black-and-white photograph of him in the lobby; on corporate pickup trucks custom-wrapped with “All-One!”; in a swirly electric-blue portrait of him in his ubiquitous thick sunglasses with a bottle of peppermint soap that hangs in David’s office; in a giant quote about Spaceship Earth painted on a jewel-toned wall of the All-One! Cafe.

“We feel like we’re custodians of this amazing legacy,” said Mike, 48, “and we want to make sure that we don’t just rest on the shoulders of our grandfather.”

In practice, that has meant pushing for a lot more than just “The Moral ABC.”

Dr. Bronner’s in its modern era has evolved into a vehicle for outright activism. It pledges that “all profits not needed for business [are] dedicated to progressive causes and charities.” Last year that amounted to $8.7 million given away, more than a third of its bottom line.

The company donates to more than 300 nonprofits, a vast lineup that includes organizations devoted to environmental conservation, drug policy reform, income equality, animal welfare, Black Lives Matter and LGBTQ+ rights. Last year, Dr. Bronner’s released a midterm voter guide with a list of 17 state and local ballot initiatives the company felt strongly about, such as decriminalizing psychedelics and increasing taxes on the rich.

We feel like we’re custodians of this amazing legacy, and we want to make sure that we don’t just rest on the shoulders of our grandfather.

— Mike Bronner, Dr. Bronner’s president

“We’re not pushing any agenda,” Trudy Bronner said at the Anaheim expo, where she was handing out candy canes affixed with $100 bills to employees she hadn’t seen over the holidays. “There is no agenda.”

I told her I was surprised by that, pointing out that the company clearly harbors strong opinions on many social and environmental issues.

“Well, my son does.”

She doesn’t have to specify which son. Over the years, David has gotten himself in trouble with the law on multiple occasions for his protest antics.

A longtime advocate of hemp, David was once arrested while planting hemp seeds outside the Drug Enforcement Administration in 2009. He was arrested again three years later after he locked himself in a cage near the White House with a dozen industrial hemp plants; firefighters had to cut through the steel bars to get to him. (In 2018, Dr. Bronner’s celebrated the federal legalization of hemp farming in the U.S. after nearly two decades of campaigning for it; organic hemp seed oil is an ingredient in its soaps.)

“We take stands that aren’t popular with everybody,” David said. “People say, ‘Why don’t you just make soap?’ But then our other customers are like, ‘Do you have any idea who these people are? This is what they do.’”

Dr. Bronner’s has also been vocal about fair wages. The company is the largest it’s ever been, with more than 300 employees. Full-time permanent employees are paid at least $25.93 an hour, and the salaries of top executives are capped at five times that of its lowest-paid fully vested worker, meaning David and Mike make roughly $300,000 a year.

Employees receive annual bonuses of up to 10% of their salary, $7,500 a year for child-care costs, and free vegan lunches every day. The company offers zero-deductible healthcare and, in 2022, added ketamine-assisted therapy to its mental health benefits.

Some of its stances, particularly those concerning gun control and immigration rights, have angered consumers. But as far as the brothers can tell, sales haven’t taken a hit — something that other famously outspoken companies, including outdoor clothing retailer Patagonia, have discovered as well.

Dr. Bronner’s recorded an all-time high of $190 million in annual revenue in 2020, when people were panic-buying household products early in the COVID-19 pandemic. The company is on track to exceed that figure this year, with first-quarter revenue up 19.8% over the same period in 2022, David said.

Dr. Bronner’s continues to add new personal care products, and plans to expand its fledgling food division (besides the chocolate bars, which were launched in 2021, it also sells organic coconut oil). Despite the company’s list of 18-in-1 uses for its soaps, it now makes dedicated toothpaste, shaving soap, hair rinse and biodegradable household cleaner.

On Monday, in response to customer requests for an eco-friendly option to reuse the iconic plastic bottles, Dr. Bronner’s began selling 32-ounce refill cartons of its liquid soaps.

Like many consumer brands, Dr. Bronner’s promotes its products on its social media accounts, which feature the usual giveaways and customer testimonials. The accounts have also become bold extensions of the company’s activism.

From climate change to voting rights, Patagonia has been willing to risk backlash by taking positions on contentious social issues. It’s a risk that has paid off.

A recent post on the company’s Instagram grid featured the words, “END THE RACIST WAR ON DRUGS,” with a tiny image of a soap bottle in the bottom right corner. Another said: “SAFER GUN LAWS = FEWER DEATHS.”

“It doesn’t matter how spicy the issues we support are,” Mike said. “Nothing will compete with my grandfather putting Jesus, Buddha, Muhammad, Abraham, Hillel on his signature soap and being like, ‘This is why I’m making it,’ even though his son was saying, ‘Just call it Mint Glow.’”

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.