Column: A panicky Federal Reserve is driving us into an unnecessary recession

- Share via

Federal Reserve Board Chair Jerome H. Powell snatched the cookie jar out of the stock market’s hands on Dec. 14, when he followed up an announcement of a dovish half-point interest rate increase with a warning that the Fed didn’t think it had wrung enough inflation out of the economy and would keep raising rates “for some time.”

The stock market, which had been riding on a sugar high for a week — with the Dow Jones industrial average gaining nearly 900 points, or nearly 3% — promptly rolled over and played dead.

Since Powell’s statement, the Dow has lost more than 1,400 points, or about 4.1%.

We don’t need a recession; we don’t need sky-high interest rates. We need more workers and investment. This is not an academic debate; our future is on the line.

— Former Fed economist Claudia Sahm

The stock market’s reaction isn’t the only indication that the Federal Reserve is out of step with economic trends — indeed, that it has been trying to muscle inflation to the ground without fully recognizing, or at least acknowledging, that the recent bout of inflation doesn’t resemble past instances in its causes at all.

Nor does the Fed seem ready to acknowledge that the inflation rate has been plummeting for many months.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The number that makes it into news headlines, not least because it has been invariably cited by the Fed when it has announced its regular interest rate hikes, is an annualized rate based on the monthly changes in the trailing 12 months.

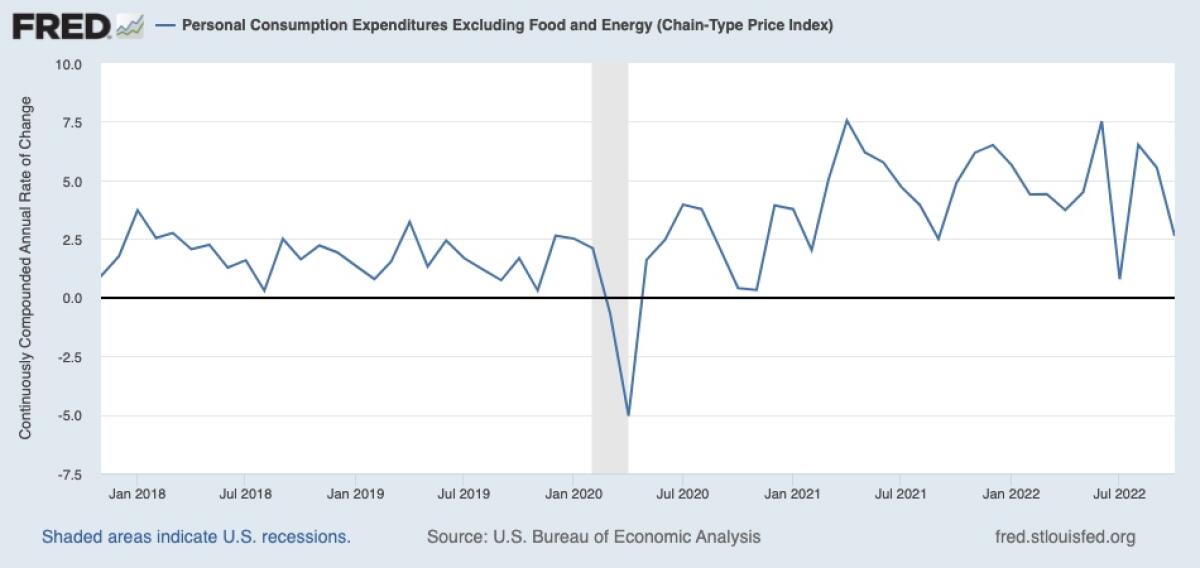

In November, that came to 7.1% for all items, and 6% for “core” inflation, which screens out the especially volatile categories of energy and food.

The 12-month figure, however, fails to track recent trends — in effect, it has been overstating the inflation rate since this summer. From September through November, prices rose by 0.4%, 0.4%, and 0.1% over the previous months, producing an annualized inflation rate of 3.7% over that period. Annualizing November’s monthly increase produces an annualized inflation rate of only 1.2%.

Powell and his Fed colleagues aren’t ready to believe the story told by this trend. In his Dec. 14 statement, Powell accepted that inflation statistics for October and November showed “a welcome reduction in the monthly pace of price increases.” But he added that “it will take substantially more evidence to give confidence that inflation is on a sustained downward path.”

Major inflation indicators are falling, suggesting the Fed may overdo tightening.

This is important because any mismatch between Fed policy and real-life economics imperils the welfare of tens of millions of Americans. As I observed in June, Powell has been a firm believer in an immutable trade-off between inflation and unemployment in which reducing inflation requires raising unemployment and reducing unemployment produces higher inflation.

For the average working American, the implications of this relationship, which is known as the Phillips Curve, are alarming, especially given today’s low unemployment rate (3.7% in November). Obstinate adherence to the Phillips Curve means throwing people out of work.

In effect, it relies on the presumption that the only way to quell inflation is through a major economic contraction, with effects that will be anything but fairly distributed.

“An economic downturn like that is likely to have long-lasting adverse effects, and the most marginalized in society will bear the brunt,” says Nobel laureate Joseph E. Stiglitz of Columbia University and the Roosevelt Institute.

Yet Powell has announced himself to be an unyielding believer in the Phillips Curve.

“We’re never going to say that there are too many people working,” he said on Sept. 21, the day the Fed announced the third of what would be four consecutive three-quarter-point interest rate increases this year. “We have got to get inflation behind us. I wish there were a painless way to do that — there isn’t.”

In his Dec. 14 statement, Powell again insisted that employment and wages were still pushing prices too high. “The labor market remains extremely tight,” he said, “with the unemployment rate near a 50-year low, job vacancies still very high, and wage growth elevated.”

Before taking a further look at Federal Reserve policy and its effect on ordinary Americans, let’s examine again what has driven prices higher over the last year.

The traditional inflation narrative is that excessive economic demand is what drives prices higher — people and businesses want to buy more goods and services than the economy can provide, so prices naturally rise. Demand can be pushed up by many factors, including the government printing too much money or keeping interest rates too low.

When that’s the case, then the Fed’s monetary tools — chiefly its ability to push interest rates higher — is the right remedy.

But that’s not what happened in the last year, when inflation was driven largely by “events outside the United States — Putin’s war in Ukraine, China’s lockdown, and post-COVID demand worldwide exceeding worldwide supplies of all sorts of materials and components,” observed former Labor Secretary Robert Reich.

Corporations are raising prices at the fastest rate since 1955, driving inflation higher.

Nothing in the Fed’s toolbox addresses factors such as the constraints on oil and gas production resulting from the Russian invasion of Ukraine or the slowdown in China production due to its stringent lockdowns. Federal Reserve monetary policy can’t do anything to increase the production of food, which would bring down those prices.

Nor does the Fed have any influence on another, little marked driver of inflation: unrestrained corporate profits. In part because they can blame the inflation narrative, corporations have felt that they can raise prices with impunity. “We’re capable of taking whatever pricing we need,” PepsiCo Chief Financial Officer Hugh F. Johnston told investment analysts during a conference call in October.

Most of the main inflation drivers are fading away without any prompting by the Fed. “Disruptions due to COVID [are] easing,” pent-up consumer demand is ebbing, and households have spent down much if not most of the stimulus payments that kept them afloat during the pandemic lockdowns that began in 2020, notes former Fed economist and self-confessed inflation dove Claudia Sahm.

Some Fed observers attribute the central bank’s hard-nosed inflation stance to its embarrassment at having overlooked the onset of inflation in 2021 and its misjudgment in dismissing the price surge late that year as “transitory.”

According to that theory, the bank is determined to preserve its reputation for sound economic management by not allowing short-term indicators to sway it from its mission to maintain price stability.

Taking steps to quell inflation by rolling back employment would cause unnecessary hardship for millions, with little gain to show for it.

That raises a concern that the Fed might err in the other direction — by pushing rates too high for too long, damaging the economy.

It’s worth noting that monetary policy operates with what can be a months-long lag, meaning that the interest rate hikes it already has put in place may be enough, if not too much.

That would warrant a pause in the rate-raising cycle next year. But Powell committed only to moving “to a slower pace” of rate increases, which he said “will allow us to feel our way.”

To some extent, the Federal Reserve may be fighting the proverbial last war in its battle against inflation. Economic observers have increasingly questioned whether its 2% inflation target is outdated — indeed, whether it was ever realistic.

Some economists, such as Olivier Blanchard of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, recommend raising the target to 3% or even higher. That would reflect the reality that over the last 92 years, the U.S. consumer price index has risen by an annual average of about 3.2%. (Acknowledgment to Ben Carlson of the A Wealth of Common Sense blog.)

It may be time to think anew about the role of the Federal Reserve in the making of economic policy. Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers praised the Biden administration in an op-ed Monday for “doing an exemplary job of respecting the Fed’s independence.”

This hands-off approach by the White House wasn’t always the case. As UC Berkeley economist Brad DeLong reports in “Slouching Towards Utopia,” his magisterial book about the last 150 years of economic policymaking, Richard Nixon made sure that his Fed chair, Arthur Burns, was made aware that unemployment needed to be low and falling as the 1972 election drew near.

Are inflation fears unreasonable? It depends on how you’re spending your money.

The Powell Fed is operating as though the political ramifications of its interest rate policies are of no import. But that’s not so, of course. The welfare of households across the economic spectrum is a quintessential political issue.

One wouldn’t want any White House to treat the Fed as an instrument of partisanship, but reminding the Fed that its activities affect not only the bondholding class but “the most marginalized in society,” as Stiglitz says, shouldn’t be entirely out of bounds.

It’s unawareness of those consequences that makes the Fed seem more than dispassionate in making policy, but callous. Bringing down inflation by slowing or even reversing wage gains, not to say throwing people out of work, will spell doom to untold households.

The most that Powell will say is that a recession may or may not be necessary to beat inflation but if it happens no one knows “whether it’s going to be a deep one or not.”

Has any economic policymaker ever been so complacent?

“We don’t need a recession; we don’t need sky-high interest rates,” Sahm wrote in a recent attack on Phillips Curve economics. “We need more workers and investment. This is not an academic debate; our future is on the line.”

Creating a low-inflation, high-employment economy may be beyond the Fed’s capabilities. It requires structural changes that include universal healthcare and paid sick time, so that the labor market isn’t kept tight by too many workers falling ill.

The Biden administration and a Democratic Congress have taken great steps to invest in America’s future, through the Infrastructure Act, Inflation Reduction Act, and the CHIPS and Science Act.

But those largely involve investments in things; what’s been missing is more investment in people, which will yield longer-lasting growth. That task, at the moment, has been left to the Fed, which is moving in the wrong direction.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.