Column: Is Elon Musk a genius or an idiot?

- Share via

At the heart of Elon Musk’s public persona is his image as an engineering and managerial genius.

How else could he build Tesla into the world’s leading electric vehicle company, creating a profitable market for an entirely new technology? Or strip down the costs of space flight to turn SpaceX into the low-cost bid-winner for government rocket launching?

Musk’s image has won him a legion of adoring fans, many of whom see him as a savior of a globally warming Earth or, alternatively, the savior of humanity through his plan to transport civilization to an unpolluted Mars.

You become a hero to fringe people, and then they embrace you.... It must be very seductive.

— John P. Moore, Cornell medical school

That image has taken a hit in recent months, thanks to Musk’s misadventure with Twitter.

The doubts originated with his whimsical offer last April to buy the social media platform for $44 billion, his transparent wriggling to get out of the vastly overpriced deal, and his ultimate capitulation in the face of the near-certain prospect that a Delaware court would order him to complete the transaction at the original agreed price.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Musk’s actions since taking over Twitter on Oct. 27 have been so destructive to the platform’s functioning and reputation that the question is raised of whether, rather than being a genius, Musk is in fact an idiot.

Perhaps that’s extreme. But it’s proper to examine how and why someone so unquestionably successful in his business career thus far has gone off the rails now.

The doubts about whether Musk knows what he’s doing have intensified in the 11 days since he assumed ownership of Twitter.

On his first day in charge, he fired the company’s top executives. Since then, he has taken a series of steps that have unnerved the platform’s community of more than 200 million users and prompted its most important advertisers to suspend their Twitter ad campaigns.

With whims of iron, Zuckerberg and Musk are bringing their companies to the edge of the grave, and shareholders and users have no say in the outcome.

Among other things, Musk fired Twitter’s top management and a large cadre of the staff assigned to screening tweets for hateful and bigoted content and blocking offenders.

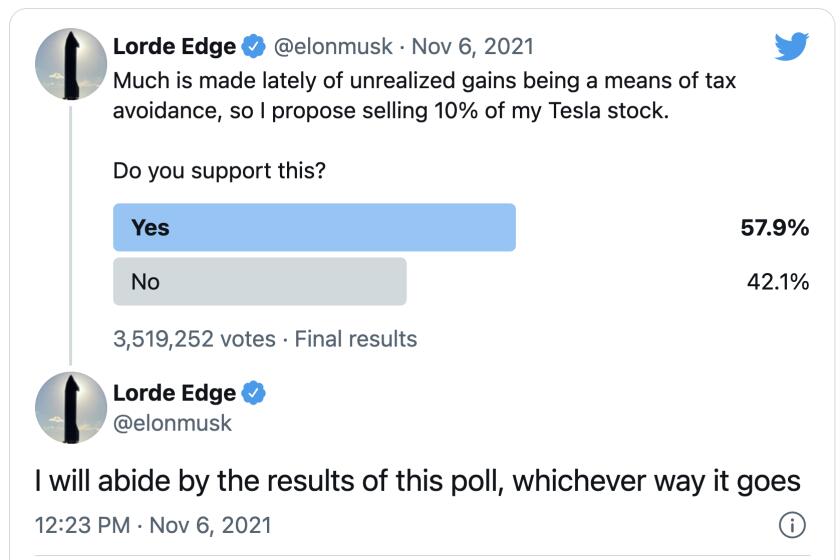

He has replaced Twitter’s identity verification policy, which ensured that prominent account holders were who they said they were and endowed their profiles with a blue checkmark, with a system awarding the blue check to anyone willing to pay $7.99 a month for it.

Musk has also issued confusing and contradictory tweets about his approach to content moderation in the guise of upholding “free speech.” That has left users wondering whether Twitter is about to become a haven for hatemongers, racists and antisemites.

In the first day after Musk took over, tweets using the “n-word” increased by 1,300%, according to the data analysis firm Dataminr, quoted by Bloomberg.

Uncertainty about the tone of content on Twitter has prompted at least temporary ad suspensions by General Motors, Audi, General Mills, Mondelez (the maker of Oreos), Pfizer and numerous other companies, according to their statements and other reports.

Musk has responded to the suspensions truculently. In a Nov. 4 tweet he blamed the suspensions on “activist groups pressuring advertisers.” He added, “They’re trying to destroy free speech in America.” (It’s unclear whether he was referring to the advertisers or the purported “activist groups.”)

In a subsequent tweet, he threatened to subject fleeing advertisers to “a thermonuclear name & shame.”

None of this, obviously, is likely to make Twitter look like a more alluring destination to advertisers. Whether they ultimately return, one would think that any brand managers at consumer companies who advise their bosses that now is the time to double down with their spending on Twitter will be placing their careers in jeopardy. No company led by even marginally intelligent executives wants to risk its reputation by associating with tweets celebrating racism, antisemitism or hatefulness in general.

Twitter can be a funnel of valuable information, or a pipeline for a Niagara of verbal sewage. An absolutist approach to free speech means, well, more sewage.

What Musk doesn’t appear to recognize is that his own behavior is driving away users and advertisers. Since his takeover, he retweeted a crude, crass and fabricated conspiracy theory about the violent assault on Paul Pelosi, the husband of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco).

He also retweeted, approvingly, a quote ostensibly defending free speech and commonly but erroneously attributed to Voltaire; it’s more reliably attributed to an American neo-Nazi named Kevin Strom.

How could someone so reputedly smart do such stupid things? To begin with, it’s not unusual for someone with a distinguished and accomplished career record to veer into crackpotism. Among the best known examples in science and engineering are Nobel laureates William Shockley and James D. Watson.

Shockley received his Nobel in 1956 as a member of the team that invented the transistor at Bell Laboratories. His management skills were so atrocious that he single-handedly destroyed his own company, Shockley Semiconductor.

He subsequently became known for advocating the overtly racist theory that welfare and relief programs prevented natural selection from killing off “the bottom of the population,” giving “inferior strains” such as (in his view) Black people, “increased chances for survival and reproduction.”

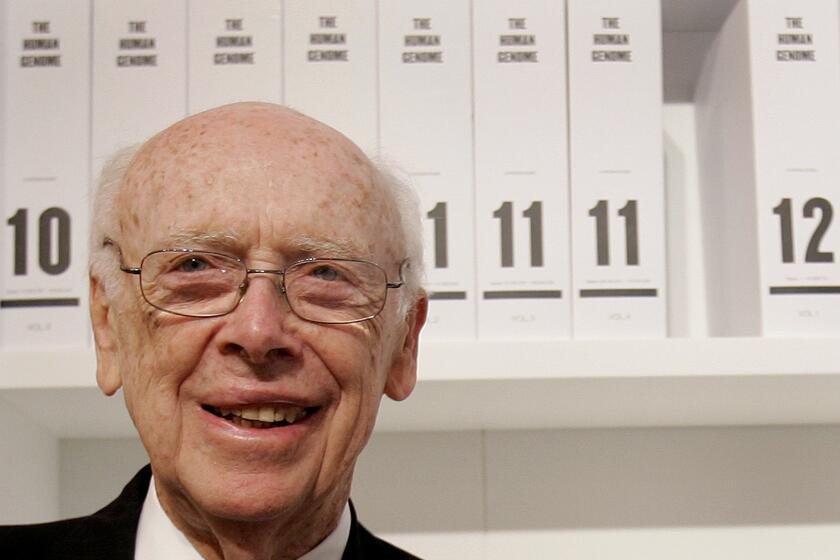

Word emerged over the weekend that James D.

Watson, who won his Nobel with Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins for their discovery of the double-helix structure of DNA and later headed the Human Genome Project for the National Institutes of Health, veered into asserting that Black people are intellectually inferior to whites and attributing the difference to genetic factors.

The claims turned him into a scientific “unperson,” in his words, and lost him sinecures at business and scientific institutions.

Both men’s arguments are contradicted by science.

The phenomenon “extends way beyond science—it’s a human condition,” says John P. Moore, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Cornell’s medical school who has written about the career of Peter Duesberg.

A distinguished UC Berkeley molecular biologist who claimed that HIV was not the cause of AIDS and described the disease as “a fabricated epidemic,” Duesberg was consequently “dismissed by his peers and ridiculed by his colleagues,” as Richard Horton, editor of the British medical journal the Lancet, observed in 1996.

Moore attributes some of these renegade behaviors to midlife crises suffered by smart individuals whose careers or professional recognition hasn’t lived up to their expectations. Racked by professional jealousy, they seek validation from other communities.

“You become a hero to fringe people, and then they embrace you,” Moore told me. “If you have that psychological need for some kind of affirmation from people you’re interacting with, it must be very seductive.”

David Gorski, a veteran debunker of pseudoscience, identifies “hubris, arrogance, and ego gratification” as traits of trained physicians who turn into quacks and anti-vaxxers.

Elon Musk thinks tax policy is a game. He should be made to pay.

One might point to Joseph Ladapo, a graduate of Harvard Medical School and former faculty member at UCLA Medical School, who has spearheaded Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’ campaign against the COVID vaccines and presumably receives validation from the approval of DeSantis, who appointed him.

Those circumstances may not fully fit Musk, though his emergence as a champion of anti-liberal conspiracy theories certainly has made him a darling of the far right. More relevant may be the observations of Oxford psychologist Kevin Dutton in his 2012 book “The Wisdom of Psychopaths.”

Dutton defines psychopaths as not necessarily violent or criminal but as those who are “fearless, confident, charismatic, ruthless, and focused” — qualities that can be beneficial for, say, surgeons or pro athletes, and would seem to suit Musk perfectly.

They need to be kept under control. “If you push all of them to max,” Dutton argues, the product will be “no use to anyone.” But if they’re wielded by degree, “you may well have a surgeon who’s a cut above the rest.”

Musk seems to have turned up his qualities of fearlessness, confidence and ruthlessness to the max. One consequence appears to be his resistance to learning anything from business history — or, indeed, from his own business career.

Musk has fallen into the trap of hubris by misreading the success of Tesla and SpaceX as testaments to his personal wisdom. Both companies, however, have relied on unusual, if not unique, advantages.

Tesla has collected enormous government subsidies — $3.6 billion in federal and state grants, rebates and tax abatements dating to 2006, according to the subsidy tracker at the nonprofit Good Jobs First. That figure doesn’t include a $465-million loan issued by the Department of Energy in 2010 to help fund Tesla’s electric vehicle technology development, which has been repaid.

Florida’s new surgeon general, Joseph Ladapo, has questioned the safety of COVID vaccines, despite overwhelming evidence that they are safe and effective.

Nor does it include the federal rebate of up to $7,500 that Tesla buyers received through the end of 2019, a total of more than $1.5 billion spent to make Teslas more affordable. The credit expired after Tesla sold its 200,000th vehicle. It will resume next year, albeit applicable only to the company’s least expensive sedan, the Model 3.

Tesla buyers have also received a total of $436 million in California state rebates; at least 18 other states have had some sort of incentive program in place.

Those subsidies saw Tesla through periods in which its financial weaknesses might otherwise have led to the company’s extinction.

Tesla also has benefited from being the only game in town for much of its existence, as the company hasn’t faced serious competition in the mass market for electric vehicles until very recently and rivals are still in the process of tooling up.

Musk must realize that Tesla is facing lots of headwinds just now. The company’s stock has fallen by 50% since it peaked almost exactly one year ago.

As for SpaceX, it owes much of its success to its president and chief operating officer, Gwynne Shotwell, who runs the day-to-day activities at the firm. Musk deserves credit for hiring Shotwell away from Microcosm, an El Segundo rocket company, and staying out of her way while taking credit for the company’s achievements as a government contractor.

Twitter is different from both those companies. Twitter isn’t in line for government handouts and even for its most devoted users it isn’t close to the only social media platform and nowhere near the largest. For advertisers, Twitter is a marketing option, and even before Musk’s takeover, not the most inviting one in the social media space.

Musk also hasn’t internalized the lesson taught by such marketing fiascos as the introduction of new Coke in 1985, which the Coca-Cola Co. itself labels “one of the most memorable marketing blunders ever.” Its lesson was that you shouldn’t make abrupt changes to your product that alienate your old customers before you’ve attracted new ones.

Another lesson is not to make changes in a company until you understand it. Musk bulldozed Twitter with undiscerning changes in its management, policies and personnel, sowing chaos in ways he plainly didn’t anticipate. After firing half its staff, he discovered that he eviscerated some departments Twitter needs to function; the company has started to invite some fired workers back to work.

The problem may be that Musk saw Twitter through the lens of his own experience as a user. He had among the largest user bases on the platform, and one that both followed him slavishly and also attracted a surfeit of fake accounts and bots. Some of his friends and followers were getting suspended or banned from Twitter for abusive tweets, which affronted his personal definition of “free speech.”

He thought everyone felt the way he did, because he made no effort to determine how Twitter looked to the average user and its advertisers.

It’s possible that Musk’s take-no-prisoners approach will make Twitter stronger in time. At the moment, however, its very future is in doubt, hobbled by an estimated $1-billion annual interest bill from Musk’s takeover debt while it hemorrhages users and advertisers.

That’s all on him. He may have looked like a business genius before now, but at the moment the only thing he has accomplished with Twitter is to make himself look stupid.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.