Getting rowdy in Palm Springs? The party police are coming for you

- Share via

PALM SPRINGS — Mitch Nabhan had been patrolling the streets of Palm Springs for six hours when the call came in about a house on Calle De Maria.

A native of the desert town, he didn’t need to look up the address. Nabhan turned the wheel on his city-issued Chevy Volt and sped off, hoping to keep his response time under his goal of 25 minutes.

“I know practically where all of these addresses are,” he said, zipping past low-slung Midcentury Modern homes, adorned with ocotillo, agave and palo verde trees.

As Nabhan drove, a co-worker back at the police station, adjacent to Palm Springs International Airport, looked up the address and confirmed the three-bedroom property was a short-term rental. That meant the tenants had to abide by some of the nation’s toughest rental compliance rules. Nabhan, a 6-foot-2-inch former high school football player, was the long arm of the law, prepared to enforce the rules with a dog-eared citation book. The first violation: a whopping $500.

“I have a sense of responsibility, a sense of duty,” he said. “The rules are very clear.”

Palm Springs is a year-round tourist draw thanks to its art scene, progressive sensibilities and poolside vibes. Big annual events, such as the Coachella Valley Music and Art Festival and the Stagecoach country music festival, both in nearby Indio, as well as several tennis and golf championships, bring in thousands of additional visitors.

Short-term rentals have been operating in Palm Springs since the 1990s, but the city formally adopted regulations in 2017 to allow but regulate them — sparking years of legal disputes between residents who say rentals ruin the city’s character and property owners and merchants who profit from the tourism spending.

Nabhan arrived at the house within seven minutes of the call to the city’s short-term rental hotline. The line is monitored 24 hours a day, with a team of six compliance officers ready to respond. The caller complained about loud music at the home. Short-term rentals are prohibited from generating music or loud noise that can be heard beyond the property line.

By the time Nabhan stepped out of his car at Calle De Maria, two other compliance officers had arrived at the scene, ready to act as backup if things got out of hand. Each code enforcement officer had completed the same arrest and firearms training as peace officers, although they are armed only with radios and citation books.

The house in question was quiet. Nabhan turned on his decibel meter and pointed the microphone toward the home. The verdict: nothing, just the hum of nearby street traffic.

Not ready to give up, Nabhan and the other compliance officers waited five minutes. Still nothing to warrant a citation.

The surging popularity of short-term rentals, booked through sites such as Airbnb, Homeaway and Vrbo, has forced cities across the country to respond. New York, Santa Monica and other cities have sought to limit the ability of property owners to rent, arguing that the rentals only worsen an already bad housing shortage. Other cities, such as Portland and San Francisco, allow the rentals but impose strict rules to keep the properties from ruining the quiet residential feel of the neighborhoods.

Palm Springs falls into the latter category. The city has approved more than 2,300 short-term rental permits. During popular tourist events nearly every one is booked. Taxes from the rentals generated $15.4 million for the city last year. The fees charged to property owners cover the cost of the compliance officer program, which also frees up police from spending hours dealing with noise complaints.

Though the desert city allows property owners to offer short-term rentals, its enforcement mechanism is more ambitious than in many municipalities. That includes a 24-hour hotline and a full-time staff of short-term rental regulators, whose salary begins at $26.82 an hour.

“At the beginning, we had one call after another,” said Patrick Clifford, one of the first compliance officers. He now oversees the team. “Then the numbers went down when [property owners] found out it was serious and we weren’t giving warnings.”

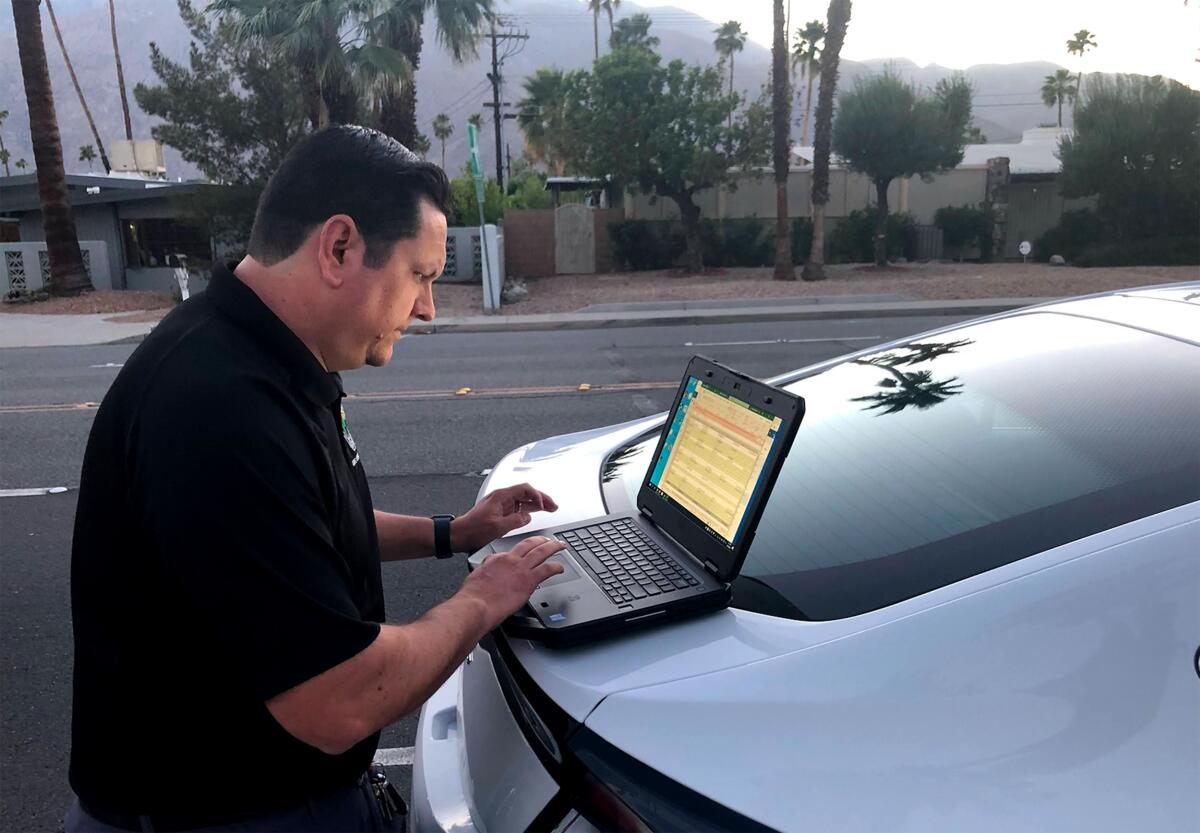

Nabhan started work on a recent Friday around 10:30 a.m., checking up on the city’s 28 storefront cannabis dispensaries, ensuring that customers aren’t partaking of the product outside the dispensaries, among other possible violations. By the afternoon, he was focused almost exclusively on short-term rentals.

After the Calle De Maria call, he called the property manager for the house. A contact number for the owner or a property manager for every short-term rental must be on file with the city. The list was on his digital tablet.

It was not a call the property manager was happy to get. “Oh, oh,” the property manager said after Nabhan identified himself. “As soon as you said ‘code compliance,’ I was like, ‘Oh, damn.’” Nabhan didn’t catch the renters in the act of being loud so the call was just a warning.

There was good reason for the dread in his voice. Renters who violate the rules pay the citations — starting at $500 for the first violation, $1,000 for the second and $1,500 for the third. But if three citations are recorded at a property within a 12-month period, the city suspends that landlord’s rental permit for two years.

The stakes are high. The properties, mostly single-family homes, generate an average of about $700 per night, according to the finance website Money.co.uk. During the Coachella music festival, the nightly rate jumps to an average of $1,700. If the city revokes a permit for two years, a property owner could lose out on tens of thousands of dollars in rental revenue.

That might explain why the volume of complaints to the city’s hotline has dropped from 991 in 2020 to 571 last year even as tourism rebounded during the second year of the pandemic, according to the city.

Some Palm Springs property owners are extra cautious: They have installed noise monitoring devices in their rental homes, which alerts them if a high decibel reading is detected.

Murray Cox, founder of InsideAirbnb.com, a group that has been monitoring the growing popularity of short-term rentals since 2015, said Palm Springs’ efforts are designed to allow rental properties to exist without having neighbors suffer too many consequences.

“What they are doing seems not so much restrictive but it’s more about managing the quality of life,” he said.

A call came in to the hotline about 5:30 p.m., complaining that a short-term rental property had four or five cars parked in the driveway and at the curb. A Palm Springs ordinance limits one car for every bedroom in the property. That means only three cars can be parked in front of a three-bedroom house, even if additional guests stop by for a visit.

Nabhan called the property owner, a woman named Brenda. She explained over the phone that the renters had only three cars and were not violating the rules. Although she was not currently in the house, she left her car in the driveway. A fifth car at the curb did not belong to the renters, she said.

That’s still a violation, Nabhan told her. To avoid a citation on her record, Brenda promised to move her car immediately. “I try to screen my guests well,” she said, adding that she had installed sound monitors in her house. “I don’t think they are going to be a problem.”

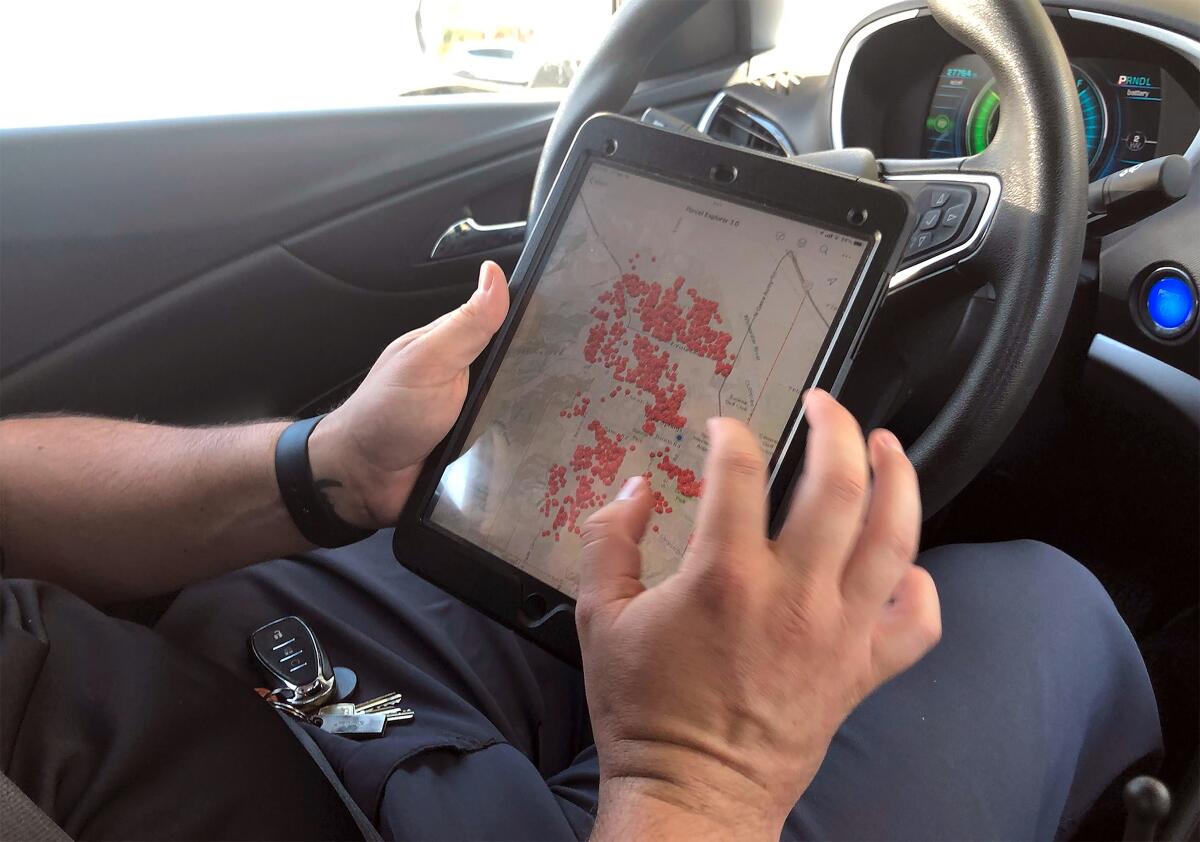

Later that night, Nabhan executed what he calls “proactive patrol.” That means he rolls down his windows and cruises slowly through neighborhoods replete with short-term rentals, listening for violators. “That house is a rental. That house is a rental,” he said, while cruising along Navajo Drive.

He pulled up a map of the city. Red dots represent homes that have a permit for short-term rentals. Nearly 7% of the city’s homes are represented by red dots, including the home where Nabhan grew up, near the high school where he played football, tennis and water polo.

A call came in to the hotline at 7:05 p.m. Loud music at a house on Jill Circle. Nabhan arrived within 10 minutes and noticed six cars crammed into the tight driveway. He took photos with his phone. Thumping music blared from the home, rattling the windows.

Nabhan opened an app on his phone, dubbed Shazam, that can identify a song within seconds. If there is a dispute later over the noise, he can include in his report the name of the song he heard. But the song was a club mix so the app failed to identify it.

The city’s records showed the house was not supposed to be rented that weekend.

After he banged on the door several times, two young men, each holding plastic cups, appeared at the door. They seemed confused by Nabhan’s questions. One young man in a tank top repeatedly asked for Nabhan’s name. A young woman in a cut-off shirt stepped through the door. She was annoyed that the music had been turned down. “But it’s my birthday,” she complained.

An older man with a beard came to the door, ushered the others into the house, and explained to Nabhan that the house was not being rented. The party was thrown by the property owner, who was on his way home. Nabhan confirmed the story with a phone call to the owner. The city’s noise ordinance is more lax for property owners. So too are limits on cars for property owners. Nabhan put away his citation book and warned the partiers to lower the music.

The next morning, Nabhan was back in his Chevy Volt, expecting to hand out several citations. After all, Coachella festival fans were probably drinking and partying in rental homes — pregaming — before the next night of music.

A call came in at 11:40 a.m., complaining about too many cars at a three-bedroom home on West Stevens Road. Nabhan arrived but heard no music. From his phone, he pulled up a satellite photo of the house. The pool was on the southwest corner of the property, but even from the property line closest to the pool he heard nothing to warrant a citation. The renter, a young shirtless man who identified himself as Jose, came to the door and said only three of the cars on the street were owned by guests in the house. “We are trying to work with you,” the young man said.

Shortly after 1 p.m., Nabhan picked up a call that a property owner of a rental on Park Drive was “proactively” evicting a group of renters who were making too much noise. The flat beige house was hidden behind a wall of hedges. The renters, several young men and women, wearing scowls on their faces, were tossing luggage into two cars parked on the street. Two Palm Springs police officers, arms folded, stood by their patrol truck in the street, making sure the eviction went smoothly.

The property manager, Josh Atchley, watched the scene unfold from the curb. A noise monitoring device in the home alerted Atchley to music by the pool, playing beyond 50 decibels. The renters booked the five-bedroom house for four nights but Atchley said he decided to evict them three days early to avoid a citation from Nabhan — and a strike against the property.

“That strike is a big deal,” Atchley said.

Nabhan slid back into his car. There was no need to take out his citation book, again. As a tool, it has become more of a deterrent than anything else.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.