Column: Neil Young, Joe Rogan, and the reason why boycotts work

- Share via

Neil Young may have gotten something started.

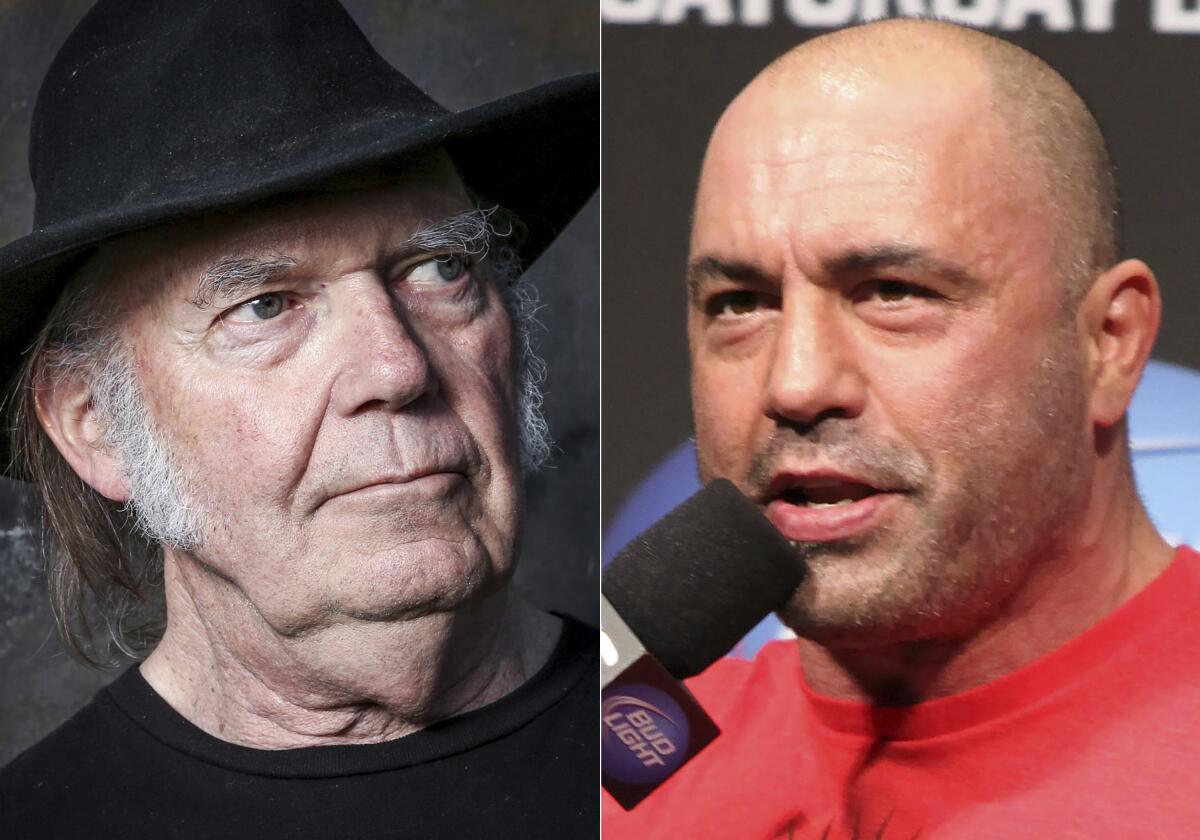

On Jan. 24, the veteran rock star made public his intention to pull his music off the streaming service Spotify to protest its mainlining of COVID-19 misinformation into the brain stems of its subscribers.

Other prominent musicians have followed suit, notably Joni Mitchell and Nils Lofgren. David Crosby, who collaborated with Young in the group Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, expressed support but said that he didn’t have the power to join Young’s boycott because he had sold the rights to his own music catalog.

They can have Rogan or Young. Not both.

— Neil Young, regarding Spotify

Even the Duke and Duchess of Sussex — Harry and Meghan, to you — have been “expressing concerns” to Spotify about COVID-19 misinformation on the platform, with which they have a deal. (The Obamas, who also have a podcast distribution deal with Spotify, have been silent, however.)

Young, 76, specifically targeted his protest at Spotify’s marquee podcaster, Joe Rogan, who has been a prime purveyor of dangerous COVID-19 hooey.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“I am doing this because Spotify is spreading false information about vaccines — potentially causing death to those who believe the disinformation being spread by them,” Young wrote in a letter briefly posted on his website. “They can have Rogan or Young. Not both.” (A slightly different version of his statement is posted there now.)

Spotify made its choice, leaving the Rogan podcasts up and removing Young’s music. The streaming service has asserted that it’s merely a platform for musicians and entertainers to distribute their material, but that doesn’t hold water: Spotify pays Rogan and others to post their content exclusively on their service — in Rogan’s case, $100 million over an undetermined period of time.

That may be why Spotify tried to mollify critics by announcing over the weekend that it would post a “content advisory” on any podcast episode that incorporated a discussion about the pandemic.

The advisory will direct listeners to a repository of “data-driven facts, up-to-date information as shared by scientists, physicians, academics and public health authorities” about COVID-19.

Whether Young’s protest will continue to grow among leading musicians is impossible to say just yet. But he did provide a service to the cause of counteracting COVID misinformation by pointing the finger at one of its leading sources and highlighting how it spreads.

A couple of days ago, the Red Lobster restaurant chain announced that it was bailing out on Tucker Carlson’s Fox News TV show, becoming at least the 20th advertiser to pull the plug.

That’s been a prime function of boycotts through the ages. Even if they don’t prompt consumers, advertisers or others to abandon the boycott target in the short term, they often work to focus public attention on the target’s behavior in the long term.

The grape workers strike and grape boycott of 1965, for example, lasted five years before it resulted in a union contract for farmworkers. The United Farm Workers lettuce strike and boycott began in 1970 and resulted in a California labor law reform in 1975.

We’ve written about the principle of boycotting before, most recently in relation to advertisers fleeing Tucker Carlson’s Fox News show, an anti-NRA campaign in 2018, and the thunderous silence by major corporations about Texas’ appalling antiabortion law. It’s one of the few ways that ordinary consumers have to make their views known by exercising their options to buy or not to buy.

Critics of boycotting are almost always those whose oxen are being gored, so of course they’re against the practice.

Boycotts are not illegal, except in narrow circumstances such as secondary boycotts, in which a union tries to persuade a neutral employer to pressure an employer with which the union has a dispute. (This prohibition comes from the anti-union Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, which should be repealed.)

So it’s proper to look more closely at Young’s actions — and at Rogan’s method of spreading deception while pretending to be merely its innocent conduit.

Let’s start with Young’s protest. Critics have denigrated this as an attempt at censorship, an example of “cancel culture,” or an attack on Rogan’s right of free speech.

It’s nothing of the kind. Young isn’t a government agent; he has no power to censor or silence anyone. He does have the right to express his own views and to manage his properties as he sees fit.

Young offered Spotify a choice, knowing full well that he might incur the consequences himself — Spotify had represented 60% of the streaming of his music, he said on his website, with almost every record of his available on its platform. (His music is available on other streaming platforms, to which he directed his fans.) This was free enterprise in action.

The call by David Hogg, a survivor of the Parkland, Fla., school shooting, for a consumer boycott of Laura Ingraham’s advertisers has turned the spotlight again on the perennial questions about boycotts — Do they work?

As for “canceling” Rogan, as at least one right-wing commentator has asserted, that’s nonsense. Rogan is said to be the most popular podcaster in the world. Even if that service dumped him, the chance he would be silenced is nil.

Focusing attention on what Rogan has been saying, however: That’s priceless.

In his comments about Rogan, Young referred to an open letter to Spotify that has been posted by more than 200 medical and scientific professionals. The letter objected to Rogan’s repeated spreading of “misleading and false claims on his podcast, provoking distrust in science and medicine,” and specifically to a Dec. 31 episode featuring Robert Malone, a prominent COVID conspiracy theorist.

During the podcast, Malone made unsupported assertions questioning the safety and efficacy of COVID vaccines, accused the Biden administration of censoring adverse information about COVID treatments, and promoted the drugs hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin as COVID treatments — claims that have been debunked by medical science.

Malone stated on the podcast that “a third of the population” has been “hypnotized and totally wrapped up in whatever Tony Fauci and the mainstream media feeds them.”

The reference was to Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, a top scientific advisor to presidential administrations dating back at least as far as Bill Clinton, and a target of irrational right-wing animus.

Rogan, apparently feeling at least some heat, has posted a response to the criticism on Instagram. There he tried to counter what he called a “distorted perception of what I do ... based on sound bites or based on headlines of articles that are disparaging.”

Rogan played the “just asking questions” card, describing himself as “not a doctor, not a scientist,” but “just a person who sits down and talks to people and has conversations with them.” He said he’s merely interested in talking to people who have “differing opinions.” He acknowledged that “some of my ideas are not that prepared or fleshed out.”

Could boycotts help restore some civil discourse on political issues?

Sorry, but that won’t do. Rogan’s self-defense was an example of gaslighting in its most undiluted form.

He’s not a neutral conduit of “differing opinions,” but a vector of known duplicity and mendacity.

Rogan wishes to portray himself as an agent in the search for truth, arguing on Instagram that some things that were denigrated as “misinformation” in the past are now accepted as truth. He mentioned claims that were treated in the past as misinformation but now are ostensibly accepted, that the vaccines would not protect you from contracting COVID, that cloth masks were ineffective, and that the virus might have escaped from a laboratory.

In fact, the first two of these assertions were never part of mainstream scientific thought — experts never claim that a vaccine works as a 100% safeguard against infection, and cloth masks are considered effective to some degree against the spread of COVID, just not as effective as N95 masks. There is no evidence whatsoever that the virus escaped from a laboratory, and the assertion is accepted today largely by conspiracy mongers.

More to the point, Rogan has often presented COVID misinformation not merely as part of the battle among “differing opinions” but as fact.

He endorsed a ludicrous claim by the far-right mouthpiece Alex Jones that the vaccines involve “actual microchips being injected into your arm.” He called the vaccines “technically a gene therapy,” which is absolutely untrue. And he has promoted hydroxychloroquine and invermectin as treatments for COVID, for which there is no evidence.

In a rational world there would be no excuse for this. In this world, and with his multimillion-viewer audience, Rogan’s assertions pose a danger to public health and to the health of listeners who accept the statements they hear on his podcast as guidelines. He likes to say he’s just an entertainer, but far too many of his followers treat him as more than entertainment.

That means he has a responsibility not to fill their heads with dangerous lies. Spotify, as his platform, has the same responsibility. Rogan and Spotify have not faced up to their duty to their audience. Neil Young, Joni Mitchell and the others who have voiced their objections have taken it on themselves to point the way.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.