Column: Another day, another billionaire whining about a wealth tax

- Share via

Whatever you may think of U.S. economic performance, there can be no doubt that America leads the world in its production of whining billionaires.

The latest to make his appearance — excuse me, reappearance — in the crybaby ranks is former hedge fund manager Leon Cooperman, 78, whose net worth is pegged by Forbes at $2.5 billion.

Cooperman appeared Nov. 11 on Bloomberg television and radio to crab about proposals for a “wealth tax” — he called it “all baloney,” though a viewing of the tape suggests he was about to use another label beginning with “B” and caught himself just in time.

The general populace is not in alignment with the progressives.

— Billionaire Leon Cooperman

He was also solicited to give his view of how to define “wealth.”

Bloomberg anchor Tom Keene opened the conversation by disdaining the notion that $400,000 in annual income is “filthy rich.” He asked Cooperman to join him in bemoaning the travails of a doctor or surgeon collecting $400,000 and “deemed by liberals to be ‘rich.’”

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Let’s leave aside the fact that almost no one, liberal or otherwise, deems the $400,000 threshold to mark the “filthy rich.” It’s just a benchmark cited in President Biden’s tax policy to meet his promise not to increase taxes on the middle class by providing a sizable cushion.

Let’s observe, however, that a $400,000 income places a household among the top 1% of earners in the U.S., which is “rich” by any definition.

Yet to Keene’s question whether he would define $400,000 as “wealthy,” Cooperman replied, “I don’t think so.” He obliged Keene by launching into a digression about how American doctors are “totally screwed by the government,” citing “the controls over their income.”

Cooperman didn’t specify what these “controls” might be, but it’s proper to observe that whatever they are, American doctors on average are the richest in the world.

U.S. physicians earned an average of $313,000 a year in 2019, according to an international survey by Medscape. That was about twice the income of the runners-up, German doctors.

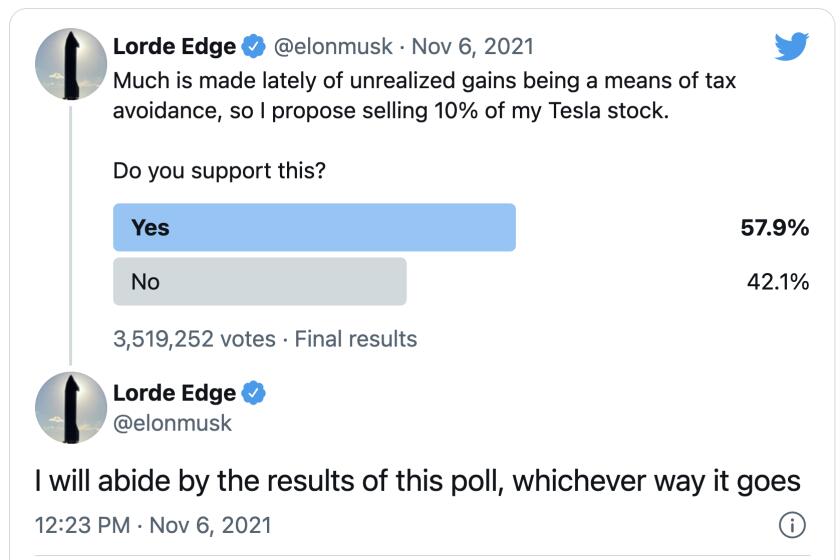

Elon Musk thinks tax policy is a game. He should be made to pay.

The average income of American primary care physicians was about $232,000, about 75% higher than their German colleagues, and specialists earned an average of $326,000, more than twice that of German specialists.

Most of Cooperman’s other remarks require fact-checking, but before we get to that, let’s note that this sort of grousing by American billionaires isn’t all that new. Nor is it limited to Cooperman.

Elon Musk, the Tesla chief executive, reputed richest individual in the world and living proof that wealth on an unimaginable scale can’t buy you maturity, responded to a comment by Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), that “we must demand that the extremely wealthy pay their fair share. Period,” with a tweet of his own: “I keep forgetting that you’re still alive.”

Musk has been a stalwart critic of a wealth tax, which I’m sure has nothing to do with the fact that he would pay it, bigtime. Back in October, he responded to a wealth tax proposal by Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), by suggesting that it was merely a stalking horse for a tax increase on the middle class, which is absurd.

“Eventually,” Musk tweeted, “they run out of other people’s money and then they come for you” — transparently an attempt to suggest that Musk and the average working American were in the same boat, tax-wise. Does anyone seriously buy that?

Billionaires’ complaints about their treatment tend to have a feverish quality. Back in 2014, billionaire venture investor Tom Perkins provided an especially crass example of the genre in a letter to the Wall Street Journal.

Perkins wrote: “I would call attention to the parallels of fascist Nazi Germany to its war on its ‘one percent,’ namely its Jews, to the progressive war on the American one percent, namely the ‘rich.’”

Cooperman, to his credit, hasn’t gone that far.

The wealth tax that so concerns Cooperman and Musk has been proposed in several different forms. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), with whom Cooperman waged a somewhat profane war of words in 2019, would have calculated the value of all household assets and levy 2% a year on net worth above $50 million, and a 3% tax on every dollar of net worth above $1 billion.

Wyden’s version would apply to taxpayers with more than $1 billion in assets or more than $100 million in income for three consecutive years.

Tradable assets such as stocks and bonds would be valued every year for the tax, whether they were sold or held; under current law, capital gains are taxed only when they’re sold, and if they’re held until the owner’s death, the embedded tax is extinguished without ever being paid.

Since Cooperman has most recently taken up the cudgel against the concept of taxing billionaire wealth, we should give a bit of his history.

Cooperman, the son of Polish immigrants, came up in the world via his own bootstraps, with an assist from taxpayers who kept his alma mater, Hunter College in New York City, tuition-free while he studied there. Free tuition ended there in 1976. Cooperman says he has pledged to give away all his fortune to charity.

President Biden wants to step up the war on tax cheats, so of course the GOP and banks object.

Cooperman became a partner at Goldman Sachs, then left to start his own hedge fund, Omega Advisors. He was charged by the Securities and Exchange Commission with insider trading in 2016. The charges concerned trades Cooperman had made in a pipeline company on behalf of Omega.

Cooperman chose to fight the charges but ultimately settled with the SEC for $4.95 million in fines and penalties and an agreement to hire an outside compliance expert to oversee Omega’s activities through this year. Cooperman didn’t admit or deny the charges, and asserted on Bloomberg, “I won the case with the SEC.”

It’s unclear whether the agency would agree with him: In its announcement of the settlement in 2017, the SEC said the deal requires “Cooperman and Omega Advisors to pay significant fines for their misconduct.”

Under indulgent questioning by Keene and his co-anchor Lisa Abramowicz last week, Cooperman was given the latitude to utter a raft of misleading and erroneous statements, all unchallenged.

Cooperman’s points, and his historical citations were, to be charitable, selective. He said, with smug satisfaction, that the recent elections showed that “the general populace is not in alignment with the progressives.”

Whatever one makes of the elections, the general populace has expressed in opinion polls strong agreement with numerous positions typically labeled “progressives”: Large majorities favor abortion rights, tighter gun control and stricter anti-pandemic policies.

Nearly two-thirds of respondents in a Reuters poll last year agreed with a wealth tax, endorsing the view that “the very rich should contribute an extra share of their total wealth each year to support public programs.” Nevertheless, Wyden’s wealth tax proposal has been judged DOA in Congress.

That these sentiments aren’t reflected in legislation doesn’t indicate that they’ve fallen out of favor, but rather that legislators aren’t in alignment with the populace.

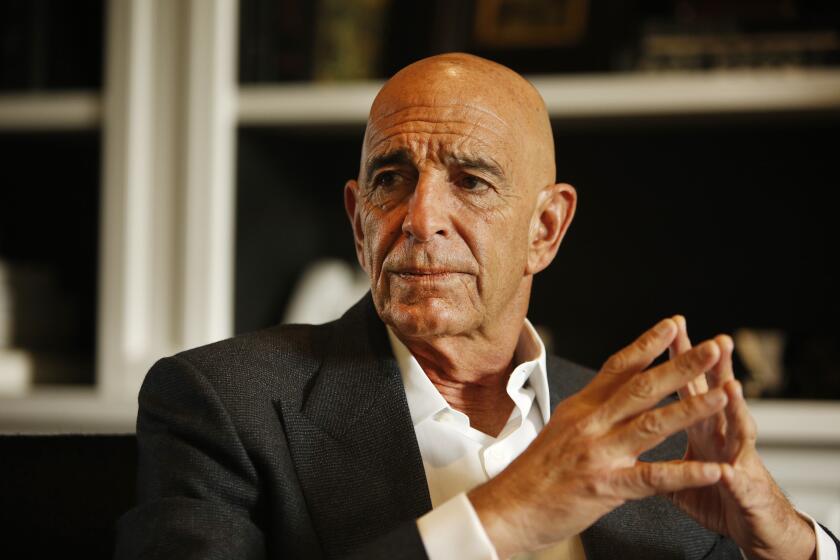

In giving Tom Barrack a platform to allegedly promote his United Arab Emirates clients, Bloomberg and Charlie Rose demonstrated the industry’s faults.

Asked by his Bloomberg interlocutors about the “vilification of the rich,” one of his recurrent themes, Cooperman said, “I respect Obama as an individual, but he started this whole thing.”

Well, not hardly. Cooperman overlooks a line of historic rhetoric: Theodore Roosevelt, for example, blasted a broadside at “malefactors of great wealth,” by which he meant E.H. Harriman of the Union Pacific Railroad and J. P. Morgan, among others, in 1907.

Cooperman said the country ought to “coalesce around the question of what should the maximum tax rate be on wealthy people.” He didn’t explain how to do that, but there’s been plenty of evidence of a public consensus over time.

The top rate was in the 80%-to-91% range until 1961, when it was applied to income over $400,000 (or $3.7 million in today’s dollars), then 70% until 1981, when it applied to income over $215,400 (about $685,000 today). It’s now 27% on income over $523,600, not counting a net investment surcharge of 3.8% on the wealthy for some investment income.

Cooperman asserted that if the federal government wishes to raise more money, “we don’t need new forms of taxation,” we should “deal with the loopholes” in the tax code.

Cooperman mentioned a rule that favors real estate investors and the carried interest loophole that delivers a tax break to hedge fund operators. (Cooperman’s Omega hedge fund appears now to be mostly his own money, so he’s probably not gaining much if anything from the carried interest rule.)

But Cooperman didn’t mention the biggest tax loophole of all: the preferential tax rate on capital gains. That tax tops out at 20%, compared with the tax on wages and other ordinary income, which tops out at 37%. President Biden has proposed raising both top rates to 39.6%, plus the 3.8% net investment surcharge.

But as I’ve reported, the wealthy would certainly go to the mat to protect their capital gains preference, since they get a disproportionate share of their income from capital assets.

An effort to be the first billionaire in space is the biggest vanity project in history.

According to the latest Internal Revenue Service statistics, covering the 2019 tax year, taxpayers with $10 million or more in income reported an average of $15 million in income from capital gains. Middle-class taxpayers with incomes of $100,000 to $200,000 reported average capital gains of $10,750.

None of the conversation between Cooperman and his Bloomberg interlocutors was especially surprising. A line from Upton Sinclair applies to the Bloomberg folks: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

As for Cooperman, his views are a good illustration of my favorite insight from an economist, which I’ve quoted many times. It comes from Herbert Stein, who was Richard Nixon’s chief economist.

In a 1996 op-ed for the Wall Street Journal devoted to a debate over how progressive the U.S. tax code should be — that is, how much more of their income the rich should pay than the middle or working class — Stein offered “one law derived from 60 years of observation...: Whatever is the existing degree of progression, people who pay the top rate will think it is too much.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.