Column: Billionaire anti-deficit hawks are already attacking Biden’s spending plan. Ignore them

- Share via

I’d say that you could set your watch by how quickly the anti-deficit crowd piled on President Biden’s Build Back Better program after its first component, the infrastructure bill, moved toward passage, but I’m not sure there’s a timepiece on Earth that can measure time spans that small.

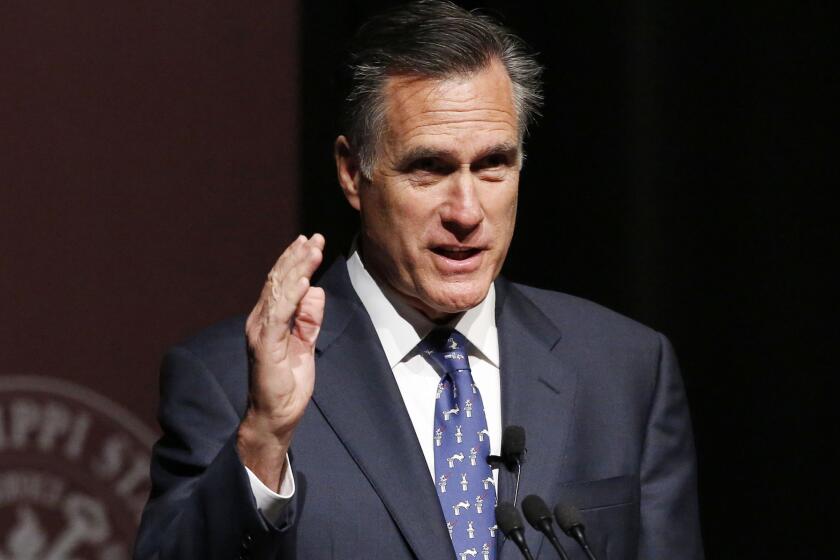

The infrastructure bill was passed by the House and sent to the White House for Biden’s signature on Friday evening. That very morning, even before the vote, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield) sent out a tweet labeling it a “socialist spending scam.”

This was about a bill that would bring California, the state McCarthy ostensibly represents, the largest share of funding in the country for road and bridge upgrades, healthcare enhancements, public transit and much more.

Will our children be impoverished by better access to pre-K schooling? Giving their families help affording child care, or allowing them to attend community college for two years tuition-free?

It would relieve economic pressures on the 13% of McCarthy’s congressional constituents living in poverty and improve services to the 55% of the residents in his district’s Tulare County and 45% in its Kern County who are dependent on Medicaid (known in California as Medi-Cal).

But, sure, it’s a “socialist scam.”

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

McCarthy, like many others in his GOP caucus, are effectively hostages to the deficit hawks who have dominated Washington political discourse at least since the 1990s.

They stand firmly in favor of cutting Social Security and Medicare benefits, arguing that these are luxuries the country can scarcely afford. After the 2008 financial crash, their demand for austerity forced President Obama to settle for a rescue program that was so skimpy it hobbled the economic recovery for the better part of a decade.

You can see them mobilizing for an inflation-based attack on Biden’s plan already, citing the warning by former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers early this year that the pandemic relief bill enacted in March would overheat the economy. Summers himself, however, doesn’t believe the latest inflation figures warrant abandoning the new program — not only are they smaller in total over 10 years, but they‘re paid for through higher taxes and represent “a valuable investment in the country’s future,” he told Andrea Mitchell on Thursday on MSNBC.

The program is “as likely to reduce the price level a few years out as it is to increase the price level,” he said. “If I were in the Congress I would surely vote for this bill in the latest form that we have seen.”

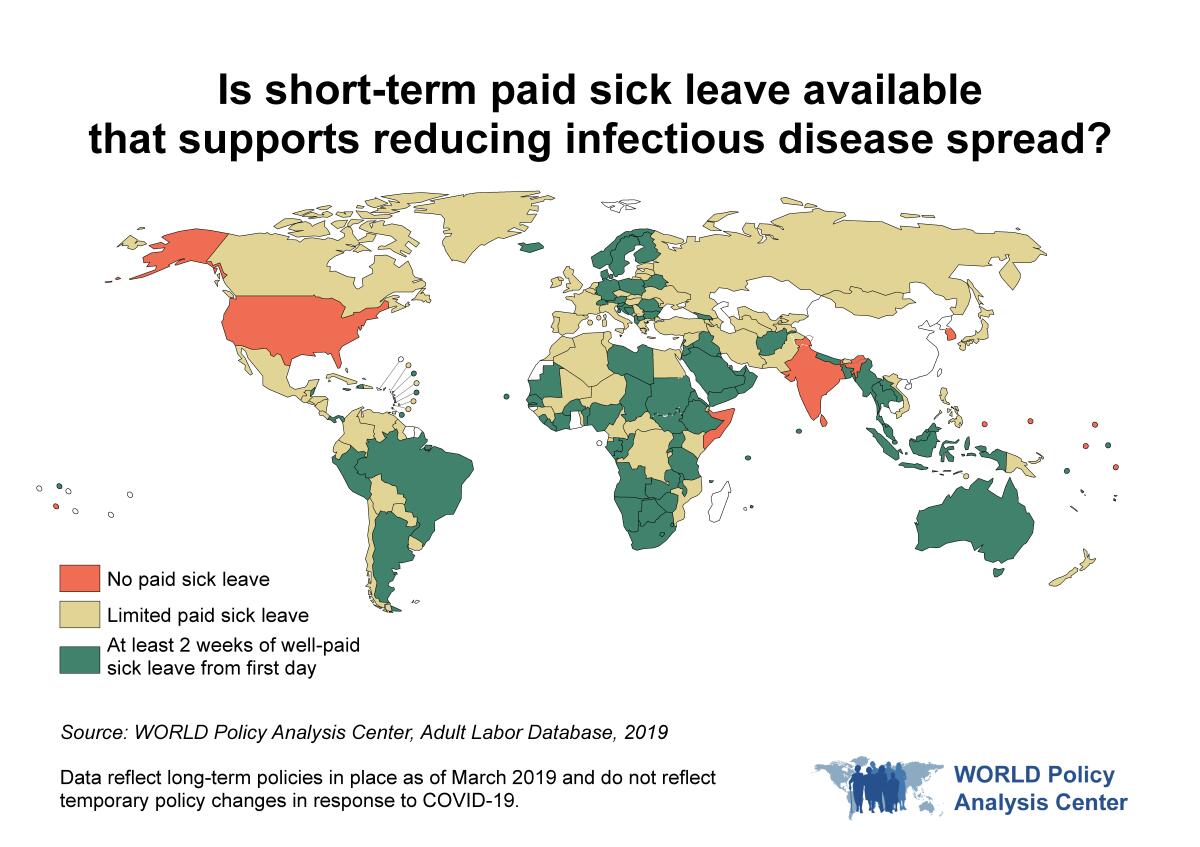

Hand-wringing over the federal deficit helps explain why America’s social programs are so meager compared with those in other developed countries. Until the situation was partially and temporarily rectified by the first pandemic relief bill last year, the U.S. offered no nationally mandated paid sick leave, which placed us right up there with India and Somalia.

Do you know what the reconciliation bill would pay for. Here are key provisions.

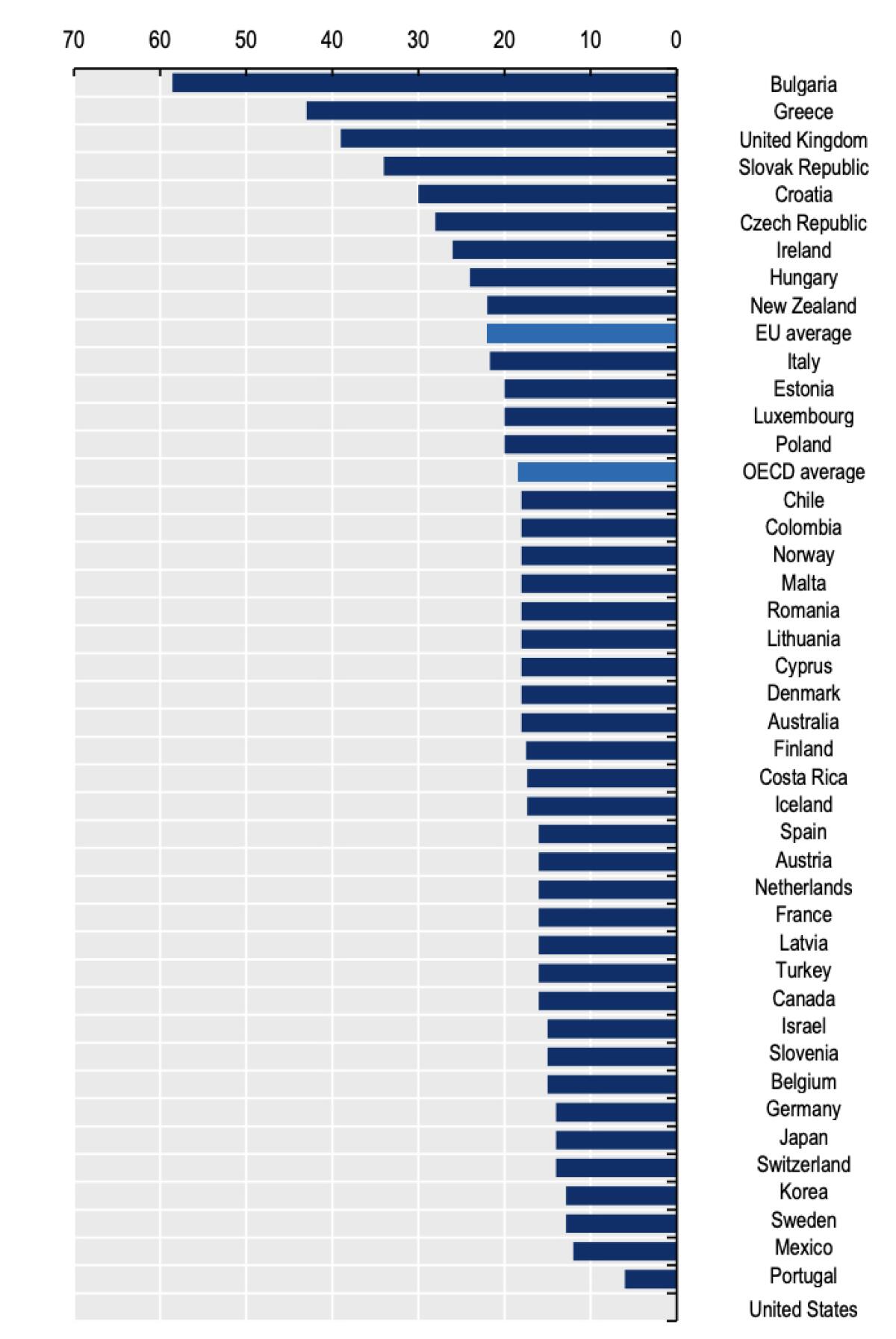

Uniquely among member states of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the U.S. mandates zero weeks of paid parental and home-care leave for new mothers; the OECD average is 51.5 weeks.

The leading hive of deficit hawks in Washington is the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, which jumped out ahead of the pack with a news release on Sept. 27 demanding that no vote on Biden’s Build Back Better Act take place until it receives a full score — that is, a multiyear accounting of the measure’s fiscal effect — from the Congressional Budget Office.

The CRFB’s headline, “No Score, No Vote,” promptly became a mantra for opponents of the Biden plan, appearing as a hashtag on tweets by congressional Republicans.

In light of the bipartisan CBO’s reputation for probity and integrity, this might be taken as a testament to the GOP’s fiscal conscientiousness were it not, shall we say, so situational. The CBO’s judgments were roundly disdained by Republicans during the Trump years, when the office threatened to maim GOP hobby horses such as tax cuts by issuing pessimistic projections about their effect on the federal deficit.

The day of “relying on some nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office ... has probably come and gone,” Mick Mulvaney, then Trump’s budget director, said in 2017. Now that Democrats are in the White House and hold House and Senate majorities, apparently that day is back.

Given the CRFB’s prominence in the anti-deficit discussion, it’s proper to examine its history.

Although Washington pundits take the committee’s self-description as an “independent source of objective policy analysis,” it’s neither neutral nor especially objective. The general thrust of its commentary and recommendations tends to protect the interests of investors, particularly bondholders, who oppose deficit spending out of fears it will trigger inflation, which saps the value of their assets.

Yet as investment manager and financial sage Barry Ritholtz observed a few months ago, “I have heard the same things over my entire adult life from people who are opposed to government deficits: they repeat the same arguments again and again, warning us — despite none of the dire things they are warning us about ever come true.”

The CRFB bears the imprint of its major patron, the late hedge fund billionaire Pete Peterson. From 2012 through mid-2020, the Peter G. Peterson Foundation contributed at least $12 million to the organization, according to foundation tax returns. Peterson sat on the CRFB board from 2012 until his death in March 2018.

Peterson was a persistent advocate of cutting Social Security benefits, a campaign that the CRFB generally adopted. Among its objections to Trump’s 2017 budget proposal was that it failed to “focus on controlling the rising costs of Social Security and Medicare.”

Deficit hawks are trying to undermine federal spending, and they’re still wrong.

The committee’s Social Security manifesto called for raising the retirement age, slowing the growth of benefits for “higher earners” (not specified) and increasing payroll tax revenue chiefly by imposing the tax on previously exempt wage contributions to some healthcare plans and other benefits — but not on unearned income such as dividends and capital gains, which are mostly collected by the rich.

In the 1990s, the committee was apparently willing to lend its reputation for fiscal conservatism to the tobacco industry, with which it partnered to create the Cost Containment Coalition, which lobbied against an excise tax on tobacco being considered by the Clinton administration by arguing that healthcare reform should be paid for by eliminating inefficiencies in healthcare rather than through new taxes.

During Obama’s term, the CRFB was a big supporter of the Simpson-Bowles fiscal commission, which also advocated cutting benefits. Erskine Bowles, a former Clinton chief of staff who was the nominally Democratic half of the eponymous commission leadership, currently sits on the CRFB board.

To be fair, the CRFB is at least consistent in its judgments. The committee was highly critical of the Republican tax cuts of 2017, based on its assessment of their potential to pump up the deficit. In strictly mathematical terms, its analyses can be useful and dependable; I’ve cited them myself on occasion.

Still, the central flaw in the argument of deficit hawks such as the CRFB is that they approach budget policy chiefly as a mathematical exercise, without paying much attention to the effect of policymaking to people on the ground.

To the hawks, federal spending is nothing but dollars going into an incinerator, impoverishing our children and our children’s children. They ignore or at least minimize the truth: that most of this spending is about investing in the future.

President Trump’s budget landed with a thud this week on Capitol Hill, where even conservative Republicans pronounced it “dead on arrival” and quailed at its proposed sharp cuts to social welfare programs such as food stamps, Meals on Wheels and Medicaid.

Will our children be impoverished by better access to pre-kindergarten schooling? Giving their families help affording child care, or allowing them to attend community college for two years tuition-free? Providing support for their mothers and fathers to stay home with them in the first months of infancy, or when they’re sick?

Will they be impoverished by the roads paved, bridges repaired, airports upgraded, high-speed rail links built? Cleaner air today and an opportunity to stave off global warming?

Yet thanks partially to pressure from deficit hawks, free community college has been cut from Build Back Better, as has been all but a one-year extension of the child tax credit (Biden wanted to make it permanent) and paid family and medical leave.

The CRFB is still discontented with the bill currently on the table, grousing in a news release this week that despite revenue offsets, “the result is a roughly $200 billion deficit increase over 10 years.”

The arithmetic works out to an increased deficit of $20 billion a year. To put that in perspective, it would represent a 2.03% increase in the 2019 deficit of $983 billion, and a 1.09% increase in the projected 2022 post-pandemic deficit of $1.84 trillion.

As a percentage of 2022 projected U.S. gross domestic product of $23.5 trillion, the increase would come to less than one-10th of 1%.

Yes, we’re talking about real money, but for that modest increase in money that the government is already spending to combat a historic public health and economic emergency, the nation would receive a major improvement in its social safety net and in future opportunities for economic growth from more access to healthcare and education. It doesn’t seem like the right place to draw the line.

Social Security advocates are universally opposed to the measure, which they see as an expression of longtime conservative hostility to the program.

The CRFB isn’t entirely blind to the benefits of many programs embedded in the Build Back Better plan. But the organization advocates subjecting those of which it approves to means-testing — or as the CRFB puts it, “scaled back and better targeted.”

Means-testing, as I’ve reported, is a time-tested way of placing government programs under a permanent political cloud. It stigmatizes those programs’ beneficiaries and often subjects them to such intrusive inquiries about their income and assets that many eligible families don’t even apply.

In any event, “targeting” often isn’t necessary. Consider free community college, which was dropped from Build Back Better as part of the effort to cut the program’s cost. The CRFB acknowledges that the chances that wealthy families would exploit free community college for their scions is “relatively low.” (I’d say “really low.”)

Changing the Affordable Care Act premium subsidies from the current system that cuts them out abruptly the moment a family’s income exceeds 400% of the federal poverty limit ($106,000 for a family of four) to one in which no family needs to spend more than 8.5% of its income for a health plan, may look like a handout to the rich, but it’s self-limiting.

The average premium of a family health plan, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, is $21,342 a year. That means that subsidies to keep the premium at 8.5% or below would automatically phase out for households with about $250,000 income. That may involve some diversion of national resources to households many of us might consider rich, but it’s not a major drain because most of those families are probably already subsidized through employer-sponsored plans.

The deficit concerns expressed by Republican opponents of Build Back Better (and Democrats such as Sen. Joe Manchin III of West Virginia) are hogwash. They didn’t keep the GOP from enacting a budget-busting tax cut in 2017 that did nothing for the average American but was a gift for the wealthy.

Federal spending, as Ritholtz observed, hasn’t driven up interest rates in the bond market, crowded out private capital, choked off the formation of new businesses or crashed the dollar. It has, however, kept American household budgets afloat during the pandemic, paid for decades of public infrastructure construction, gotten us through the Great Depression and World War II.

Looking ahead, it will build more, remake the American economy to be more broadly beneficial for more people and set the stage for decades of powerful growth. What’s not to like?

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.