Column: Is Biden the next FDR? That depends on what you think about the New Deal

- Share via

President Biden’s chief of staff, Ron Klain, left nothing to the imagination on Feb. 9 when he tweeted a line from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first inaugural address: “Action, and action now.”

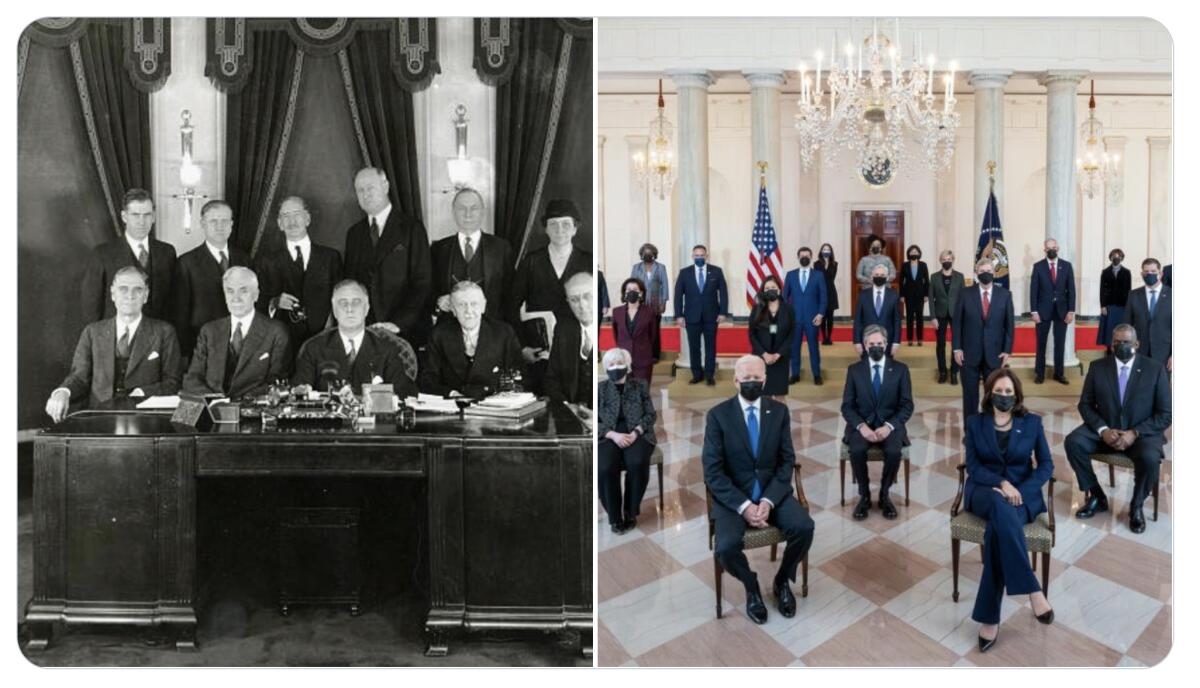

Klain repeated the allusion in another tweet a week later, and even more recently posted side-by-side photos of the Biden and Roosevelt cabinets. All this has positioned the chief of staff as the flag-carrier for an emerging political construct aiming to associate Biden’s policies with the New Deal.

Comparisons between Biden and Roosevelt are proliferating in political commentary.

The country demands bold, persistent experimentation....The millions who are in want will not stand by silently forever while the things to satisfy their needs are within easy reach.

— FDR, 1932

Historian Eric Rauchway delivered perhaps the most positive assessment in a useful interview with Greg Sargent of the Washington Post; historian Michael Lind delivered the weirdest attempt to exploit today’s political landscape to knock down FDR.

As the end of the first hundred days of the Biden administration approaches, analyses weighing his nascent record against the preternaturally active hundred days that opened the Roosevelt era will become even more common.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

There are advantages and dangers in drawing these parallels. Advantages for Biden, because the New Deal remains the repository of cherished Democratic Party values and progressive achievement even today, eight decades after FDR’s inauguration. Dangers, because the New Deal doesn’t entirely resemble the image passed down to us by history.

As I discovered in writing my 2011 book “The New Deal: A Modern History,” there is much about FDR that will surprise you, and not always pleasantly. The legacy of Roosevelt, and the expectations for President Biden, can be built up but also damaged by the comparison.

That’s not to say that as the first hundred days come to a close Biden hasn’t honored what’s seen as the tradition of inclusiveness and community established by FDR.

The Biden and FDR presidencies certainly resemble each other superficially. Both men took office as experienced politicians — Biden after a long Senate career and service as vice president; Roosevelt as governor of New York. Both entered the White House shadowed by doubts about their suitability for the presidency and about their intellectual capabilities.

Biden searches for an antitrust enforcer who could radically transform the U.S.

Biden and FDR both followed presidents who had utterly failed in a crisis, bequeathing the mess to their successors. Both launched their administrations by drawing sharp distinctions with their predecessors’ approach to governing.

Herbert Hoover’s battle against the Great Depression was hampered by his lack of imagination in wielding the political and fiscal tools within his reach. Donald Trump foundered in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic by having no discernible interest in governing at all.

The biggest problem facing those seeking parallels between Biden and Roosevelt is the mythology that has sprung up around the New Deal, which may be the most misunderstood domestic policy period in American history. Let’s examine some of the most common misconceptions.

One is that FDR was blessed with a huge congressional majority that would pass anything he proposed. On the surface, this appears to be indisputable. At Roosevelt’s inauguration on March 4, 1933, Democrats held a 58-36 majority in the Senate, or more than 60%, and 311-117 majority in the House, or more than 70%.

What’s generally overlooked is that the parties then didn’t at all resemble today’s homogenized, polarized partisan blocs. The GOP harbored a large clique of progressives, and the Democratic Party a large cadre of conservative Southerners.

In fact, the strongest opposition to New Deal initiatives tended to come from Southern Democrats, in part because they feared that it would unsettle their home states’ white supremacist politics.

Henry A. Wallace, FDR’s vice president, foresaw the fascism of Trump.

Meanwhile, one of the most loyal members of FDR’s Cabinet, Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, was a Republican progressive (he had led the unsuccessful “dump Hoover” movement at the 1932 GOP convention). Ickes and Labor Secretary Frances Perkins were the only Cabinet members to serve throughout FDR’s entire 12 years in the White House.

Another hive of anti-New Deal activity was the Democratic Party’s Wall Street bloc, which continually slandered FDR’s program as “socialism.”

After Democrats associated with Du Pont and General Motors formed the American Liberty League to uphold the party’s moneyed interests, Roosevelt offered a withering assessment, describing it as “an organization that only advocates two or three out of the Ten Commandments.... [They] say you shall love God and forget your neighbor.”

It’s tempting to think of the New Deal as an unalloyed string of progressive programs. But it’s commonly forgotten that while the first bill passed during the hundred days was the Emergency Banking Act, which saved the banking industry by temporarily granting the president near-dictatorial power over the entire banking sector, the second bill was the highly conservative Economy Act.

That measure, written by FDR’s very conservative budget director, Lewis Douglas, cut the federal budget by 25%, slashed wages of all federal employees by 15% and authorized sharp reductions in veterans’ benefits, including those for disabled vets.

Congress subsequently restored the cutbacks; FDR vetoed the restoration and got overridden by Congress. That’s an illustration of how the New Deal was really a melange of progressive and conservative policies.

The term “socialism” has been enjoying something of a vogue lately, typically used to describe policies that were part of American mainstream politics as recently as the 1980s.

FDR appointed more Black officials to high-ranking federal posts than any had before, and in most New Deal programs there was work and housing for Black Americans. But as I wrote in my book, “Roosevelt was never eager to stir the cauldron of race relations.”

FDR left overt civil rights activism to his wife, Eleanor, which gave him plausible deniability; when Southern politicians came to complain he could blame pro-Black demonstrations on “my Missus.”

It was Eleanor who personally integrated a segregated race-relations conference in Birmingham, Ala., where the racist police commissioner “Bull” Connor had to back down from his pledge to arrest violators of the segregation law, intimidated as he was by the prospect of throwing the president’s wife in jail.

But not even Eleanor could move her husband to support an anti-lynching bill in Congress, despite the rising toll of extrajudicial executions in the South and West — 63 lynchings were reported from 1933 through 1935.

“The Southerners by reason of the seniority rule are chairmen or occupy strategic places on most of the Senate and House committees,” FDR explained to a crestfallen and skeptical NAACP President Walter White at a White House meeting brokered by Eleanor. “If I come out for the anti-lynching bill now, they will block every bill I ask Congress to pass to keep America from collapsing. I just can’t take that risk.” The bill failed.

Perkins and Ickes, who had been president of the Chicago NAACP chapter, continually ran up against racist management of New Deal programs that were left to local officials to administer, typically in accordance with the racist habits of their communities.

It’s an article of faith that FDR forged the coalition of urban and minority voters and laborers that has long served as the Democratic Party core, but for Black voters it was a halting journey away from the party of Lincoln.

As late as the eve of the 1936 election, the influential Baltimore Afro-American newspaper concluded that of the four major candidates, Black voters would fare best under Earl Browder, the Communist Party standard-bearer, followed by Norman Thomas, the Socialist. FDR ranked third and Republican Alf Landon last.

But as only the last two had any chance of victory, the journal counseled voters to pull the lever for Roosevelt as an expression of “political opportunism.”

Although New Deal relief programs are often portrayed as the first Keynesian deficit-funded anti-poverty programs in American history, that’s not how Roosevelt saw them. (He met the economist John Maynard Keynes just once, when Perkins arranged an encounter. Neither participant came away impressed by the other.)

Keynesian theory was little known in the U.S. at the time and certainly wasn’t in the forefront of New Dealers’ thoughts. Roosevelt viewed programs such as the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress Administration more as devices to keep unemployed Americans fed, clothed and sheltered while the economic cycle worked itself out and recovery took hold.

FDR’s relief chief, Harry Hopkins, was brusquely unapologetic when the press and congressional conservatives attacked the WPA for the apparent triviality of some projects. “God damn it!” he exploded. “Here are a lot of people broke and we are putting them to work.”

Wall Street Democrats’ fear of Elizabeth Warren reminds us that they opposed the New Deal too.

His approach differed from that of Ickes, who as head of the Public Works Administration demanded that its projects pass rigorous scrutiny for financial efficiency and lasting public value.

The approaches worked symbiotically: Hopkins provided sustenance for more than 20 million Americans, and Ickes bequeathed the country airports, bridges, school buildings and other edifices that still do service today.

The most important difficulty in comparing Biden and Roosevelt may be the latter’s character, which was so pragmatic and protean that even his closest aides sometimes had trouble getting a handle on it.

As much as Social Security can be seen as the cornerstone New Deal program, it must be remembered that FDR almost killed it in its crib. To Roosevelt, the most important element of the Social Security Act was its reform of unemployment insurance. On Nov. 14, 1934 — just weeks before the act was to be presented to Congress — he told a conference of social insurance experts that he doubted “whether this is the time for any federal legislation on old-age security.”

Perkins, who had nursed the act into its final form, had to scramble to undo the damage, and soon brought Roosevelt around again. But despite Roosevelt’s return to his old commitment to universal pension coverage, there were still gaps. Notably, domestic and farmworkers, sectors that were disproportionately Black, were left out.

Lind asserts that this was done at the behest of Southern Democrats. In fact, it was the handiwork of the penny-pinching Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, a patrician neighbor of Roosevelt’s in upstate New York. Morgenthau, who was looking for ways to cut the costs of Social Security, argued that “transient and casual” laborers would be too difficult for the Treasury to reach to collect Social Security contributions.

It would be 15 years before Congress began adding those excluded workers to the system, under Presidents Truman and Eisenhower.

Though a granular examination of the New Deal shows its cracks and flaws, it’s important to understand that its overarching principles were inclusion, community and — as Klain notes — action. Roosevelt himself embraced those principles even if he sometimes neglected them in practice.

During his first presidential campaign, he asserted that “the country demands bold, persistent experimentation.... The millions who are in want will not stand by silently forever while the things to satisfy their needs are within easy reach.”

Furious about attacks on Social Security by his GOP opponent Alf Landon in the 1936 election and Landon’s big-business backers, Roosevelt thundered: “Only desperate men with their backs to the wall would descend so far below the level of decent citizenship as to foster the current pay-envelope campaign against America’s working people.”

FDR was building a new coalition and a new progressive tradition from scratch. Biden isn’t wrong to associate himself with the New Deal in its broad strokes, just as Lyndon Johnson exploited the same legacy to pass the Great Society programs Medicare and Medicaid.

Biden brings to the White House a predilection for action, ambition and a bow to the idea that American government works best when it works for all. The New Deal is in many ways an unfinished project, and Biden appears determined to build further upon its foundations.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.