Column: What we’ve learned — and what we still don’t know — after our pandemic year

- Share via

For Musso & Frank Grill, the venerable Hollywood institution, the past year has been one of uncertainty.

The restaurant has been closed since last March 15, when Mayor Eric Garcetti abruptly banned indoor dining or serving of alcohol, effective at midnight that night.

When conditions eased, the restaurant reopened in late June — for four days, until the state banned indoor dining again.

There are things that aren’t going to change....You need to meet people and get to know them. Body language matters.

— JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon, on a return to normality

Musso tried a meals-to-go model for about three weeks, but it didn’t work.

“The return on the to-go model wasn’t worth asking our team to risk themselves,” said John Echeverria, a member of the third generation to run Musso & Frank since it was bought by his wife’s family in 1927. “It wasn’t panning out.”

The family kept its 84 workers on the payroll and covered their health insurance for a time, assisted by $852,000 from the federal Paycheck Protection Program, which provided loans to small businesses that could be forgiven if they spent the money on payroll and crucial expenses such as rent and utilities. (The restaurant qualified.)

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Restaurant customers also contributed to a $100,000 fund to cover employees’ living expenses.

But now the Echeverrias are on tenterhooks about when the state, city and county will greenlight indoor dining again.

Even if the county crosses below the state-mandated threshold of new COVID-19 cases and positive tests, allowing it to permit restaurants to open with reduced capacity, county officials say they may continue to apply more stringent standards.

“I don’t think we’ll return to normality until mid- to late fourth quarter,” meaning sometime in the last two or three months of the year, says Mark Echeverria, John’s son and the restaurant’s on-site manager.

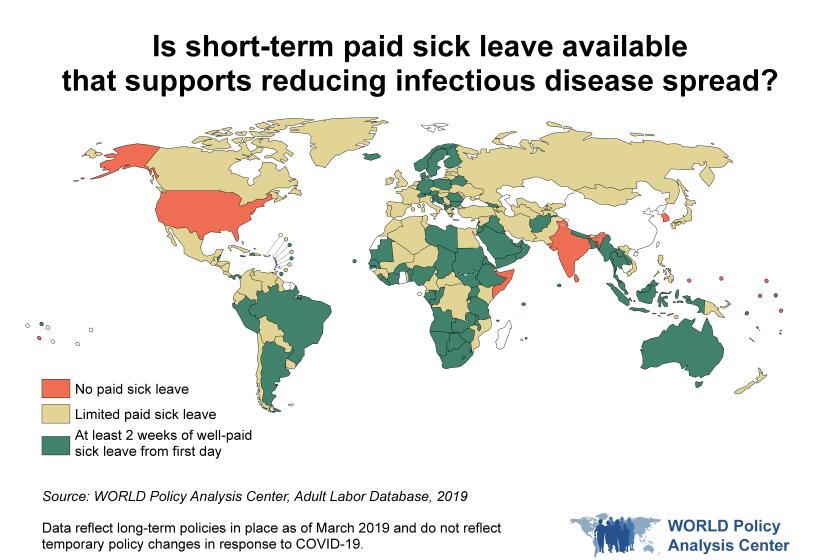

By limiting sick leave and free healthcare, the U.S. system will promote the spread of coronavirus.

Over the last 12 months, economic winners and losers from the crisis would emerge, even if for many Americans the prevailing experience has been one of grief.

Forecasts about the path to normality and its timing are almost entirely conjectural. There seems to be a growing, if vague, sense that predictions that lifestyles and business practices would be changed dramatically and forever were premature, at least.

The reasoning is that the cultures of face-to-face interactions and workplace meetings — developed over decades, even centuries — have shown their value over time and can’t be discarded so easily.

“There are things that aren’t going to change,” Jamie Dimon, chairman and CEO of the giant bank JPMorgan Chase & Co., told me in an interview. “You need to meet people and get to know them. Body language matters.”

A new New Deal would correct America’s 50-year decline and fix the COVID-19 pandemic, too.

With remote contacts “it’s harder to establish new relationships,” he says. “You can do it from a distance, but it’s not the same thing as seeing you dealing with a real problem, or going on a sales call.”

He added, “The failures of virtual world are growing. There’s less innovation, slower speed now in certain decision making, less spontaneous combustion in collaboration.”

(Dimon did make clear that however policies evolve at JPMorgan Chase, the bank would remain in compliance with accepted health and safety protocols.)

I don’t intend to belabor here the adjustments in our personal and communal lives forced upon us by the pandemic. Every society has its rituals for the common occasions of marriage, birth and death.

In the words of Robert J. Collins (author of the best book ever on life as an expatriate businessman), “People seem to need it, and society is thereby strengthened.” In the last year, all have been grievously disrupted.

But we can draw some lessons from the experience about how the world works.

One lesson is that the wealthy are seldom disadvantaged even by cataclysmic events — or at least not as vulnerable as the rest of us.

As an analysis of Forbes data on billionaires’ net worth by Americans for Tax Fairness and the Institute for Policy Studies underscores, America’s wealthiest families have weathered the economic disruptions of the pandemic year quite well.

The net worth of Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon.com, soared by more than 59% to an estimated $113 billion, the study shows — mostly on the strength of a run-up of about 85% in Amazon shares.

Amazon is one of many companies that were well-positioned to profit from emergency restrictions, thanks to its dominance of e-commerce at a time when millions of Americans had little choice but to transfer much of their purchasing online.

All in all, the total net worth of America’s 657 billionaires rose by $1.3 trillion, or 44%, over the last year, the analysis calculated. That gain alone would be enough to cover almost two-thirds of the $1.9-trillion pandemic relief package President Biden signed on Thursday.

Assumptions about which businesses profited from the pandemic — and more to the point, which ones can turn the crisis to long-term advantage — need to be assessed carefully.

Third-party food and grocery delivery services such as DoorDash, GrubHub and UberEats notched record revenues during 2020, as shoppers and restaurant-goers stayed home and made their purchases remotely.

Gross bookings at UberEats, the ride-hailing firm’s delivery arm, easily outstripped those of the company’s traditional passenger services during 2020, $10 billion to $6.8 billion, the company reported.

But Uber still recorded a loss of nearly $6.8 billion for the year. Neither of the other companies has been able to turn a surge in pandemic revenues into profits, either.

The reason may be that the profit margins still remain with merchandise, not delivery.

“We’ve never made a dollar delivering a pizza,” Domino’s Chief Financial Officer Stuart Levy told Restaurant Business last month. “We make money on the product, but we don’t make money on the delivery. So we’re just not sure how others do it.”

Companies whose stock prices rose because of their ability to exploit the pandemic market have seen investors cool off as the end of the crisis looms on the horizon.

They include Zoom Video, a teleconferencing platform so popular that its name has become generic for remote meetings. Though shares are up more than $200 in the last year, they are down more than 37% from the peak they reached in mid-October, which suggests that while remote meetings will continue, there’s doubt that Zoom will continue to dominate white-collar work and social interactions as it has in the last year.

A century ago, Sinclair Lewis predicted how America would botch the coronavirus crisis.

America’s rank-and-file stood to be losers from the pandemic. To the extent many have been able to keep food on the table and a roof over their heads, that’s been the product of record-breaking stimulus programs enacted by Congress.

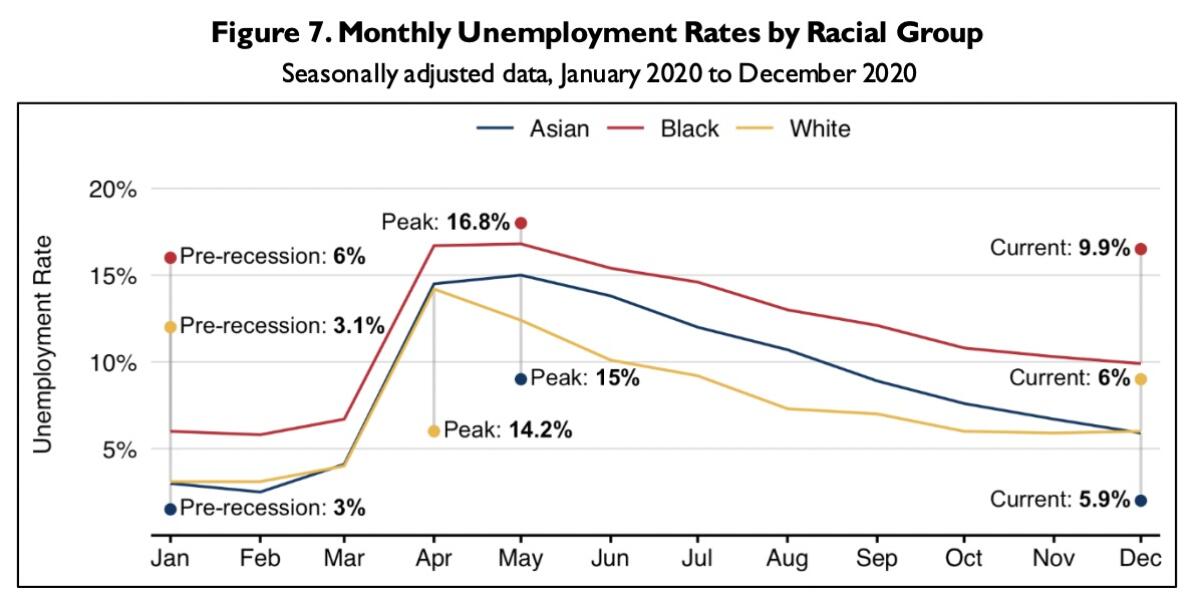

The ranks of the unemployed have shrunk since peaking at 23.1 million in April, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, but they still number nearly 10 million.

The pandemic exposed the fault lines in our workforce demographics. Unemployment rates were highest for Black workers, for whom the unemployment rate peaked at 16.8% in May, compared with a peak of 14.2% for white workers. As of February, the rate for Black workers was still 9.9%, compared with 5.6% for whites.

That’s not much of a surprise: In January 2020, before the pandemic shut down the U.S. economy, the unemployment rate was 6% for Black workers and 3% for whites.

Another divide has been between those who can work from home and those — deemed “essential workers” — who must report to a workplace.

Working from home has been a privilege of the professional and managerial class.

Among managers and professionals responding to a February survey from the BLS, about 40% had worked from home at some point in the previous four weeks; the highest percentages were in computer-related occupations (64.3%) and the law (58.2%).

That’s an exotic world for workers in the service sector such as food preparation and serving (1.9% reported working from home); personal care — think hair, nails and so on (5.9%); healthcare support (4.9%); and building maintenance and cleaning (2.6%).

America lags the world in paid sick leave, hobbling our fight against COVID-19.

It was evident from the outset that America’s unforgiving workplace and healthcare cultures would place the burden of the pandemic on ordinary workers’ shoulders.

As I observed a year ago, a huge proportion of American workers simply don’t have the economic power to stay home, whether to care for family members or even to give themselves a chance to recover from a viral infection in solitude, or the legal right to take off from work without losing their jobs or pay.

Millions of Americans, moreover, don’t have access to healthcare without shouldering significant bills. About a quarter of all American workers have no right to sick leave, according to the BLS. In service industries — where employees must report to their places of employment to work and are most likely to come in contact with the public — more than half have no sick leave.

Some employers tried to fill the gaps as the emergency unfolded. Felix Chevrolet, a downtown Los Angeles institution, offered workers two weeks of sick pay and agreed to cover employees’ share of health plan premiums until the dealership could fully open its service and sales facilities in July, its owner, Daryl Holter, told me. (Felix also received a payroll protection grant.)

But even after reopening, the dealership has had to make do with a smaller staff, going from about 105 employees to 80.

Holter says many employers will learn from the pandemic year how to conduct business differently.

That’s true of Chevalier’s Books on Larchmont, which Holter also owns.

“The bookstore survived by doing online sales,” he says. “For a period of time, that became the only way you could sell.”

That was a novel experience for a staff accustomed to face-to-face interactions with customers coming in the front door, but a learning experience. It held them in good stead when even Amazon’s vaunted efficiency broke down, leading to delays.

At first, Holter recalls, the city insisted that the store close entirely. Chevalier’s and other merchants were able to convince the city that they needed to have some employees on the premises. “I said the front door is closed but the employees are coming in the back to do online sales, check the inventory, with masks on. We were able to get that agreement.”

It’s evident that some things will change in the way we live and work.

The only thing everyone thinks they can be sure of is that at some point in the future, the COVID pandemic will become not something we confront from morning till night, but a historical memory, the way the wartime blitz is something that Londoners who lived through it tell their disbelieving great-grandchildren about.

But when? We’ll know it when we see it.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.