Column: Last year CEOs pledged to serve stakeholders, not shareholders. You were right not to buy it

- Share via

Exactly one year ago, corporate America issued a statement that appeared to mark a sea change in industry’s perception of its social responsibilities.

The Aug, 19, 2019, “statement on the purpose of a corporation” by the Business Roundtable, a leading corporate lobbying group, declared that its members shared “a fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders,” not just shareholders. (Emphasis in the original.)

The statement’s signatories — 187 CEOs of major public companies with a combined $13 trillion in market capitalization — promised to “deliver value” not merely to shareholders, but to customers, employees, suppliers and communities.

The CEOs who signed this statement know that accountability to everyone is accountability to no one.

— Shareholder rights activist Nell Minow

The Business Roundtable depicted the statement as a milestone for corporate social responsibility and a significant departure from its previous declaration of corporate purpose in 1997, when it said the paramount duty of management and of boards of directors was to shareholders.

Many observers in business, academia and the media took the corporations at their word. Wrote the veteran corporate lawyer Martin Lipton, “2019 may come to be viewed as a watershed year in the evolution of corporate governance.”

Fortune declared that the statement tossed the old standard of corporate behavior “into the dustbin.”

We remarked that the statement, in “a shocking reversal,” put “the shareholder value myth in the grave.” But we also advised viewing the commitment cautiously and wondered whether the CEOs would “do more than talk.”

So now it’s been a year. Have the CEOs done more than talk? The answer is no. If anything, the CEOs have done less than talk.

In the year since the Roundtable statement, there have been few signs that major corporations have taken real steps to serve nonshareholders that they wouldn’t have taken without outside pressure, whether from public opinion or government regulation.

The Business Roundtable suddenly declares that not only shareholders count.

Several companies have raised their minimum wages, but typically either in compliance with or anticipation of government mandates to do. Some consumer companies offered front-line workers “hero” bonuses for their work during the pandemic, but withdrew them even before the pandemic ebbed.

And business groups, including the Roundtable, have continued to lobby to roll back environmental laws and make it harder for ordinary people to have a voice in corporate decision-making.

The Roundtable statement produced plenty of skepticism among corporate critics from the outset. Scanning the list of signatories, investment manager Barry Ritholtz observed that it was “a Who’s Who of corporate behavior that has burdened and disadvantaged the very stakeholders they will now champion.”

Amazon and Apple, Ritholtz observed, had been experts at exploiting international tax loopholes to avoid billions in U.S. taxes, and Walmart and McDonald’s had fought increases in the minimum wage for years.

Shareholder activist Nell Minow observed that previous “stakeholder” initiatives tended to cloak efforts to entrench management by making them less beholden to shareholders, as happened when CEOs sought shelter from the hostile takeover craze of the 1980s.

“The CEOs who signed this statement know that accountability to everyone is accountability to no one,” Minow noted.

Chevron’s directive from shareholders: Report how you’re lobbying against the environment.

Had the companies that signed the Roundtable statement actually remade their management policies to raise the interests of customers, workers, and others above those of shareholders, argue Lucian Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita of Harvard Law School in a forthcoming paper, “the impact on society would be considerable.”

Instead, they conclude, the statement “should be viewed largely as a PR move rather than as the harbinger of a major change.”

Let’s briefly revisit the shareholder versus stakeholder debate. As I’ve reported before, the idea that a corporation exists solely to “maximize shareholder wealth” largely dates back to a 1970 essay by the conservative economist Milton Friedman, who declared that business leaders who spoke up for the social responsibility of their corporations were “preaching pure and unadulterated socialism.”

Friedman derided business leaders who talked about serving such social ends as “providing employment, eliminating discrimination, avoiding pollution and whatever else may be the catchwords of the contemporary crop of reformers.”

Those CEOs were merely “unwitting puppets of the intellectual forces that have been undermining the basis of a free society these past decades.”

Over the ensuing decades, the shareholder value ideology was evoked to justify cutting worker wages and benefits in favor of higher dividends, fighting unions, skimping on research and development and flouting environmental and labor regulations. Those efforts funneled more money to shareholders, which was the point after all.

Paying workers more, observing environmental stewardship, even making charitable donations were all well and good, according to the Friedman doctrine, only to the extent they made the company more valuable and its shareholders richer.

Employers’ gratitude for their ‘hero’ workers didn’t last long

In recent years, the tide has begun to turn. In part the change has been driven by major institutional investors such as BlackRock, whose CEO, Larry Fink — a signer of the Roundtable statement — has called on companies “to wade into sensitive social and political issues,” in part because governments have withdrawn from addressing them.

As Fink wrote last year in his annual letter to CEOs of companies in which BlackRock has large investments, “companies must demonstrate their commitment to the countries, regions, and communities where they operate, particularly on issues central to the world’s future prosperity.”

Even small investors have shown more interest in mutual funds focused on “ESG” — “environmental, social, and governance” principles. ESG issues dominate the list of shareholder proposals for annual meetings at some major corporations.

This year, a shareholder proposal demanding that Chevron issue an annual report disclosing its lobbying expenditures on climate change and explaining how they align with the goals of the 2015 Paris climate agreement garnered 53% of the votes, the first time any such proposal has won a majority at a major company.

(The proposal, which was opposed by management, is nonbinding. Management hasn’t said how or if it will comply.)

Curbing the power of big corporations became a plank in the platforms of contenders for the Democratic nomination for President such as Sens. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren and grist for Congressional committee members from both parties.

That all suggests that the Business Roundtable statement may have been a marketing-driven attempt to jump in front of a parade rather than a genuine rethinking of the “purpose of a corporation.”

Bebchuk and Tallarita question whether the CEOs ever regarded the Roundtable statement as a serious road map to change. Their evidence includes a poll they conducted of 173 signatory companies to determine whether the signing was approved by their board of directors or merely the CEO.

If the former, that would signify the intention of a major policy change, since those can only be made by a board.

They say that of the 48 companies that responded, the decision to sign was made by the CEO alone in 47. That suggests that most companies didn’t expect the statement to change how they do business

SEC rule changes would stifle shareholder voices but gratify entrenched managements.

One might conjecture that those companies willing to associate themselves with the “stakeholder capitalism” of the statement were predisposed to conduct themselves responsibly.

That doesn’t appear to be so. According to a survey by Aneesh Raghunandan of the London School of Economics and Shiva Rajgopal of Columbia, the signatories of the statement tend to have higher rates of environmental and labor law violations and pay higher penalties than their nonsigning peers. They also spend more on lobbying.

Concrete steps toward elevating stakeholders above shareholders — or even on the same plane — have been hard to identify. But not the opposite.

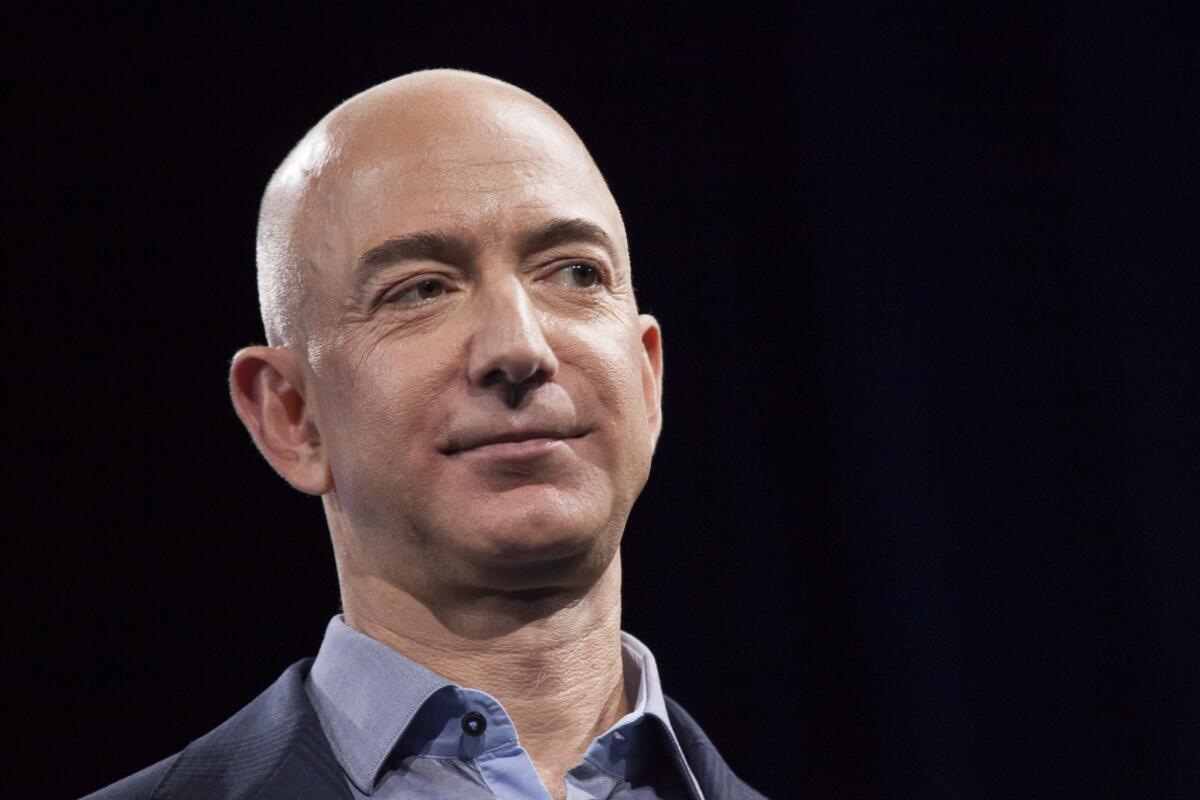

Less than a month after the Roundtable statement, Amazon, whose CEO Jeff Bezos was a signer, became the first company to renege on its principles when its Whole Foods subsidiary announced that employees working between 20 and 30 hours per week would lose access to the company health plan.

The American Petroleum Institute, which lists signatories Chevron, ExxonMobil, Marathon Oil, Noble Energy and Phillips 66 among its members, has lobbied in favor of weakening the Clean Air Act, a Trump deregulatory initiative opposed by environmentalists.

The Business Roundtable itself has lobbied in favor of a proposal before the Securities and Exchange Commission that would raise obstacles to placing shareholder proposals on annual meeting agendas — especially when they concern ESG issues.

The truth is that shareholder primacy is baked deeply into American corporate governance. CEOs and other top executives are compensated largely in accordance with their success at keeping share prices strong.

“Shareholder democracy” long has been derided as an oxymoron, like “military intelligence” or “jumbo shrimp.”

Bebchuk and Tallarita observed that among the 20 CEOs on the Business Roundtable board, an average of 91% of annual compensation was linked to performance, almost exclusively financial performance and therefore to shareholder value.

In only three of those 20 companies was a CEO’s bonus linked to a stakeholder metric, and then only modestly.

At Eastman Chemical, the performance goals included employee safety, but since no weighting was assigned to that metric, the board had wide latitude in judging it. At Marriott, the satisfaction of workers and guests was included in the performance matrix, but only weighted at 1% and 2% respectively.

At Duke Energy, employee safety was assigned a weight of up to 19% in setting the bonus for CEO Lynn J. Good, but that may have been related to the requirement that Duke report safety events to regulators, so a falloff in safety could have dire consequences for the bottom line.

The truth is that expecting corporations to remake themselves from the inside is a mug’s game. The only real option for realigning businesses to serve social interests is to mandate it from the outside, via regulations.

Warren has proposed obligating big companies to give workers significant representation on their boards, limiting executives’ ability to profit from their shareholdings while they are employed, and barring companies from political expenditures without the approval of 75% of shareholders.

The details of Warren’s proposal aren’t as important as the theme — American businesses won’t be weaned from favoring shareholders above all other until they’re forced to. As the last year has shown, they’ll talk about changing, but talk is cheap.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.