Bay Area group raising $1 billion for small businesses hurt by virus, theft, curfews

- Share via

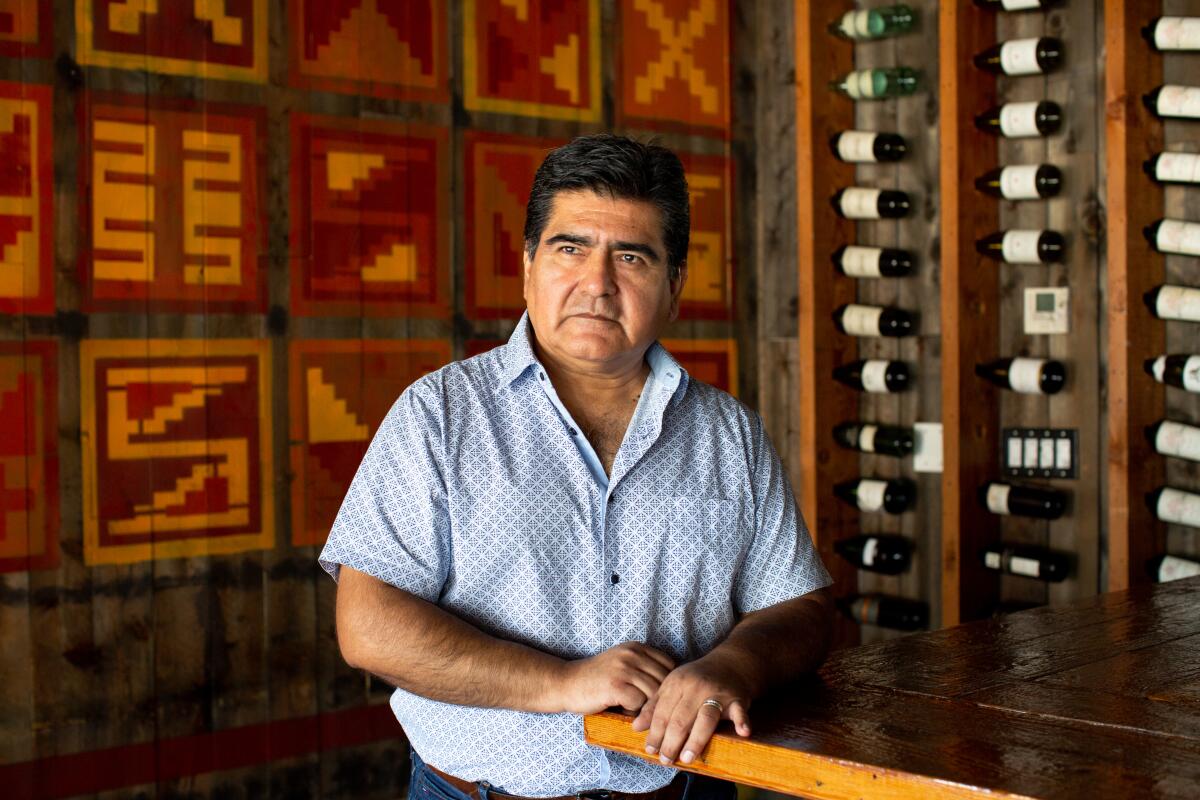

After a thief hit the Hollywood restaurant Los Balcones del Peru during a wave of protests against police brutality on Saturday night, owner Jorge Rodriguez counted himself lucky enough to laugh about it.

“He grabbed the most expensive wines we had and took off,” Rodriguez said, adding that the man left the restaurant otherwise untouched. “It looks like he had a taste for red wines. He didn’t touch the whites.”

Rodriguez maintains a grim sense of humor even as he struggles to keep his business on life support.

The restaurant sits on Vine Street, a short walk from the ArcLight Cinemas. Like other businesses that serve tourists, Los Balcones took an early hit from COVID-19, the illness caused by the novel coronavirus. “January is when we start getting all the travelers from Asia and Europe,” Rodriguez said. “We never got that traffic.”

Takeout customers trickle in and out, but his employee count is down from 43 workers to seven. He can’t open for limited seating until early July. The restaurant received Paycheck Protection Program money from the federal government, but that will soon be gone, with the resumption of normal business a distant prospect.

Millions of small businesses in California and around the country are in a similar predicament. Their livelihoods already were threatened by the COVID-19 lockdowns and the dearth of business traffic. Then, for many, came revenue losses from curfews and property damage or inventory loss due to break-ins and vandalism. Loans are hard to come by and dauntingly expensive.

Seeking to provide a lifeline, a Bay Area group created in March is launching an ambitious California-wide program to raise $1 billion in capital to help otherwise healthy small-scale establishments survive the next several months.

Community lenders, law firms, universities, philanthropies, small-business trade groups and individual volunteers have joined forces as the California Small Enterprise Task Force to drum up funding to provide cash to sustain working capital and other essential expenses until — everyone hopes — a better economy boosts customer spending next year.

“We’re trying to prevent or lessen the number of people in bread lines,” Susan Mac Cormac said. A corporate lawyer and partner at the international law firm Morrison & Foerster, Mac Cormac helped come up with the task force plan, which she sees as vital to preventing a wave of poverty. “We can’t address the economic issues of COVID-19 and the George Floyd murder without being able to provide jobs in these [low-income] communities,” she said. “And the only people that hire people in these communities are microbusinesses.”

In a March survey by the Small Business Majority advocacy and education group, 44% of small-business owners said they would have to shut down for good without immediate financial help. Many did receive forgivable loans under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act passed by Congress. But big wads of emergency federal loan money went to fast-food chains, hotels and other companies with big bank relationships and the wherewithal to hire high-priced lawyers, accountants and lobbyists.

“Federal and state funding is not reaching the companies that need it most,” Mac Cormac said. “But the need is huge.”

The expected high default rate for small-business recovery loans is translating into interest rates “way above normal times,” said Adair Morse, a finance professor at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. For the hardest-hit areas, she estimates rates “in the order of 25% to 30%, if not a lot more.” So loan programs “must at least be partially subsidized by government or philanthropy backstops,” she said.

The California task force started out mainly to offer advice to small businesses. Another early catalyst was Adam Werbach, a Bay Area environmentalist and entrepreneur. “Everyone felt devastated with the pandemic, so we drew together resources and skills to meet the need.” Students at UC Berkeley’s law school set up a hotline. The task force created a well-organized, comprehensive resource guide and posted it online.

After the flaws in federal aid programs became clear, Mac Cormac and her fellow volunteers decided advice wasn’t enough. More access to low-interest loans was needed. A lot more.

The federal Paycheck Protection Program defined a company with up to 500 employees as “small.” The California program is for businesses with no more than 75 employees. The vast majority of recipients will have far fewer than that, organizers said. The $1-billion program, called the Small Business Rebuilding Fund, is primarily a loan program, not a grant program.

Morse of Berkeley’s Haas School is helping structure the program. The main aim is to lower interest rates for small-business owners to a realistic level while “de-risking” the investments for those fronting the money.

That requires government loan guarantees and lenders with skin in the game. Businesses that apply will have to show they’ll be “viable” after the gap period. “Using limited taxpayer money, we need to do so in a way that maximizes spillovers back to the economy, so that the debt the government incurs today supports economic growth,” Morse said.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom has set aside $50 million to seed such programs, with another $50 million in his budget for legislative approval. The loan program would help small businesses access those funds. The group is lobbying Congress to add money to small-business loan programs the fund could tap. The California group is also raising money from philanthropic organizations.

Kiva, a San Francisco-based crowdfunded distributor of loans to “unbanked” small businesses worldwide, will administer the program. The loans will be pooled, Wall Street-style, with the pools, rather than individual loans, assessed for risk. Commercial lenders will be paid off first, philanthropies last. Some grants will be made to businesses that can demonstrate a strong business plan. Law firms including Morrison & Foerster and Silicon Valley powerhouse Cooley offer pro bono advice.

Mac Cormac said people from seven other states so far have approached the California group to learn about the program and possibly create their own.

It’ll take effort and cooperation, said Mark Herbert, the California representative for Small Business Majority. If small businesses can’t get access to capital, and soon, “the ripple effect and economic devastation that follows will be incalculable,” he said. “But I’m an optimistic person. I’m hopeful that policymakers and other leaders will do everything in their power to make sure we have tools to prevent that from happening.”

A billion dollars is a lot of money, said restaurant owner Rodriguez. “But it’s a lot cheaper than letting all these businesses go under.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.