The six days that broke Wall Street’s longest-ever bull market

- Share via

Investors had long grown used to records in the great stock bull market that ended last week. Longest. Calmest. Highest. It was almost inevitable that the finish would be dramatic.

The saying on Wall Street is shares take an escalator up and an elevator down, but the elevator went in both directions last week. By Friday’s close, stocks in the U.S. notched the biggest one-day rally and rout since the financial crisis. In the end, more than $2 trillion got wiped from American stocks, and global equities saw $6.3 trillion get zapped.

It wasn’t just stocks. Treasuries were up one day, down the next as liquidity worries brewed. Currency volatility — a beast that’s been dormant for years — awakened. Gold’s haven status crumbled.

This is the story of a Wall Street week for the history books.

Sunday: Oil Shock

It’s not even dark in New York when the trading week begins in earnest in New Zealand, 9,000 miles and 17 hours away. It will be a long day.

Over the weekend, Saudi Arabia has effectively declared an oil-price war after the cartel it dominates, OPEC+, failed to reach agreement with Russia. Already in the Middle East, where most exchanges operate on a Sunday-to-Thursday basis, equities have tumbled.

Currencies of energy exporters are the next to react. If the price of their key export collapses it puts immediate pressure on their economies and government finances. The Norwegian krone falls to its lowest since at least 1985 versus the dollar. The Mexican peso drops to a more than three-year low.

Seconds into trading, oil prices have already cratered. Brent crude opens 20% lower and extends losses to as much as 31%, the biggest drop since the first Gulf War in 1991.

The declines won’t stop there. Oil shocks ripple through markets because the commodity has a key role in the global economy. For the countries and companies that produce, it’s a generator of wealth. Oil’s an expensive industry, so small firms in the business tend to have high debts. And it’s an input into many costs in the economy.

What makes this oil shock worse is the timing: Thanks to the coronavirus, global markets are already on edge.

The yield on 10-year U.S. Treasuries, effectively the global benchmark, drops through 0.5% for the first time as investors clamor for safe assets. Futures on the S&P 500 join the sell-off sweeping Asian equities, and before long hit the trading curbs designed to limit the most dramatic moves while cash markets are closed.

All this has occurred before midnight in New York.

Monday: Circuit Breaker

The die is cast before most traders on Wall Street have started out for work, never mind reached their desks. Selling is sweeping Asian stocks, Treasury yields — already at a record low — are extending declines and European equities are down the most since 2016.

With U.S. futures pinned at their lower limit, investors have no way to tell exactly how bad losses will be when the cash market for stocks opens in New York. They get a clue when pre-market trading begins. The exchange-traded funds that track the main American benchmarks aren’t subject to the same limits as futures, and they point to even steeper losses.

When the bell does sound on Wall Street, the rout begins. Losses reach 7% four minutes in, triggering NYSE circuit breakers that halt trading for 15 minutes.

Meanwhile, the oil crash ripples through related products, roiling highly levered exchange-traded notes that play the price of crude.

With the S&P 500 destined for a 7.6% drop and crude set to close down around 25%, investors rush to the safest assets. The dash into Treasuries is so ferocious that the entire U.S. yield curve drops below 1% for the first time in history.

In the swaps market, inflation bets collapse. Policy makers were already struggling to spur price growth; the market believes an oil collapse and deadly epidemic will make it impossible.

The level of doubt is so high they’ll accept less than 1% to lend to the U.S. for 30 years. The decline in the yield of long-dated Treasuries is the biggest on record.

Anxiety is mounting across the markets, exacerbating strains that were already showing up in credit as investors worried about companies’ ability to service debts during the virus outbreak. The cost to protect against default on North American corporate debt surges the most since Lehman Brothers collapsed. An index of leveraged loans drops the most since 2008.

The oil crash throws a spotlight in particular on those companies in the industry with heavy debt loads, many of which fall into the riskier high-yield category.

Sensing the rising risk of a credit crunch — in which investors are no longer willing to lend to the companies and institutions that need it — the Federal Reserve lifts the amount of temporary cash it’s willing to provide markets.

Tuesday: Limits

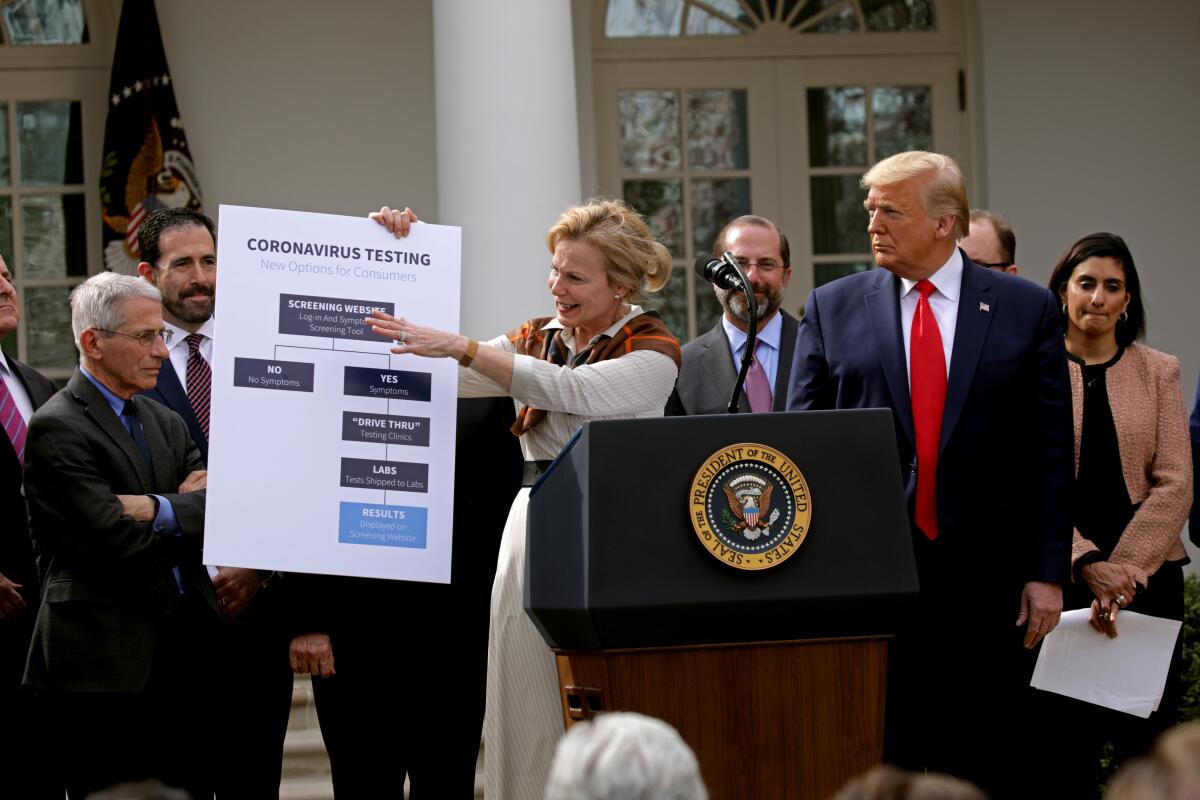

There is optimism in the air. U.S. stocks just suffered the biggest rout since the crisis, a gift for any investor looking to buy the dip. President Donald Trump has pledged “major” economic announcements later in the day. Despite a brief dalliance in bear market territory overnight, S&P 500 futures are rising. Fast.

Remarkably, a day after the contracts hit their lower trading limit, they hit the upper bound. European shares join the rebound, and while none of the moves come close to erasing the Monday rout, the mood is upbeat on hopes Trump will deliver significant measures to fight both the coronavirus and its economic impact. Even oil bounces back.

All these moves are stirring another asset class, however. Volatility has been climbing in every corner. The Bank of America Merrill Lynch GFSI Market Risk indicator, a measure of expectations for turbulence in stocks, rates, currencies and commodities worldwide, hasn’t risen this fast since the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

Developed-market shares are now more volatile than their peers in emerging nations, which are usually seen as less stable and higher risk. Bets for more oil price swings are the highest on record. But most notably, currency volatility has returned.

Foreign-exchange moves are a huge factor in international capital markets and economies, because they influence the terms of trade between nations, companies and investors everywhere. For years, implied currency volatility has been in retreat amid globalization and coordinated central bank activity, not to mention an era of perpetually low rates and quantitative easing.

Now it’s surging as policy makers rush to tackle the coronavirus impact in different ways, and as investors move their money round the world amid the market turmoil.

The dollar jumps by the most since 2016, a move some attribute to the anticipated American stimulus measures that may give a jolt to the economy. But are there other forces at work? Across global markets the cost of converting other currencies to dollars in the market for so-called cross-currency basis swaps has been creeping up.

In other words, there has been a small but steady increase in the cost of dollar funding — putting participants on high alert for stress in the system, because the greenback is the ultimate global funding currency.

Perhaps these sorts of wrinkles would have gone away if not for events today. Trump doesn’t appear at a White House briefing on the outbreak, and as the day wears on it becomes clear the promised major announcement is not coming. As Wednesday trading begins in Asia — evening in New York — futures for the S&P 500 decline again.

Wednesday: A Bull Dies

Another day, another volte face in major assets. With no stimulus details in sight in the world’s biggest economy, headlines about the virus roll in thick and fast. Italy will close all stores aside from grocery shops and pharmacies. A top U.S. infectious-disease specialist tells lawmakers the pathogen is 10 times more deadly than the seasonal flu.

The bad news culminates when the World Health Organization calls the virus spread a pandemic. In a sense, the designation was a formality in a world where governments were already taking extreme measures to fight its spread. But it crystallizes the crisis for investors; stocks are plunging around the world, oil falling again and the stress in U.S. credit markets worsening.

Gloom descends all across markets. This will be the day the Dow Jones industrial average sinks into a bear market, ending the longest bull run in the history of American equities.

In a bitter twist, for once bonds offer no protection: Investors want to ditch assets that are easy to sell, and despite mounting liquidity worries Treasuries remain among the most tradable.

Away from the virus headlines and price action, a trend is beginning. There are signs that companies in the industries hit hardest by the coronavirus are drawing down credit lines. Shares of Boeing Co. plunge 18% after it says it plans to draw down all of a $13.8 billion loan. Hilton Worldwide Holdings Inc. loses 10% when it announces it will draw some of its credit line. Private equity titan Blackstone Group Inc. asks companies it controls to tap bank facilities to help prevent any liquidity shortfalls.

By the end of the day, policy makers announce plans to ramp up cash injections in the coming weeks to as much as $505 billion in a bid to keep short-term financing markets functioning smoothly through quarter-end.

Details of U.S. fiscal action to cushion the economy from the impact of the pandemic remain sorely lacking, and all hopes are pinned on an address from the president scheduled for that evening.

The bull market in the Dow Jones index has already ended; Trump’s speech winds up sealing the fate of both the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq.

Thursday: Liquidity

Fatalities in Italy rise by a third, France closes all schools, the EU warns the outbreak could overwhelm the bloc’s health-care system and New York City declares a state of emergency.

But it’s largely background noise at this point; the selling has become self-reinforcing after an error-laden speech from Trump containing only small-bore measures to fight the virus. When the European Central Bank decides to keep rates on hold, it seems to confirm to investors that officials aren’t doing enough.

Fears for the economic outlook batter commodities anew. Oil resumes its decline and palladium tumbles more than 20%.

More dislocations appear between major assets, as gold falls along with everything else. Gold usually gains in risk-off episodes because investors consider it a safe haven, but once again it looks like traders may be selling whatever is easy to sell. Bitcoin plunges too as cryptocurrencies implode.

In the U.S., shares are routed. For the second time in a week, the S&P 500’s drop triggers a 15-minute trading halt shortly after the open. The benchmark will close down 9.5% in the biggest one-day decline since Black Monday in 1987.

The potential fiscal hit of the coronavirus suddenly shatters the appeal of the municipal bond market as a refuge, and it experiences the worst day on record.

As sentiment sours, investors and analysts start to contemplate what a sudden surge in demand will do to Treasury bills. The Libor-OIS spread, a measure of how the market is viewing credit conditions, expands to the widest level since 2009. The dollar jumps to the strongest since 2017.

With funding stresses still on display, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York injects almost $200 billion into the system and dramatically increases the amount it’s prepared to inject over the next month, promising a cumulative total above $5 trillion.

U.S. stocks initially pare losses after the surprise announcement, but the seriousness of the situation hits home. Investors now face a growing likelihood that the coronavirus will plunge the global economy into recession.

Friday: Action

The bleakest day in most markets for more than three decades seems to have awakened both policy and law makers.

The Bank of Japan follows the Fed’s liquidity move. Germany pledges to spend whatever’s necessary to protect its economy and the European Commission says it’s ready to green-light widespread fiscal stimulus for euro nations. The ECB signals it’s ready to buy more debt and regulators announce a temporary ban on short-selling stocks.

All told, it helps to distract from yet more bad virus headlines, like the European economy forecast to shrink by 1%, or Spain declaring a state of emergency.

The news of a potential fiscal response in Europe hammers the region’s bonds, but S&P 500 futures once again hit their upper limit. The Stoxx Europe 600 Index surges. Treasuries are down and oil gains, though the moves are small with investors awaiting more comments from Trump.

And then the coda: The S&P 500 powers higher by 9.3% for its biggest rally since October 2008, Treasuries plunge and oil surges after Trump declares a national emergency, signaling a stepped-up response to the crisis.

Almost 6 percentage points of the stock rally come in the final 30 minutes of trading, cutting the weekly rout that at one point reached 16.5% to less than 9%. The 10-year yield almost hits 1%. Oil, boosted by Trump’s pledge to top off the strategic supply, jumps 4.1%.

Outrageous moves to finish an outrageous week, and a fitting end to the longest ever bull market.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.