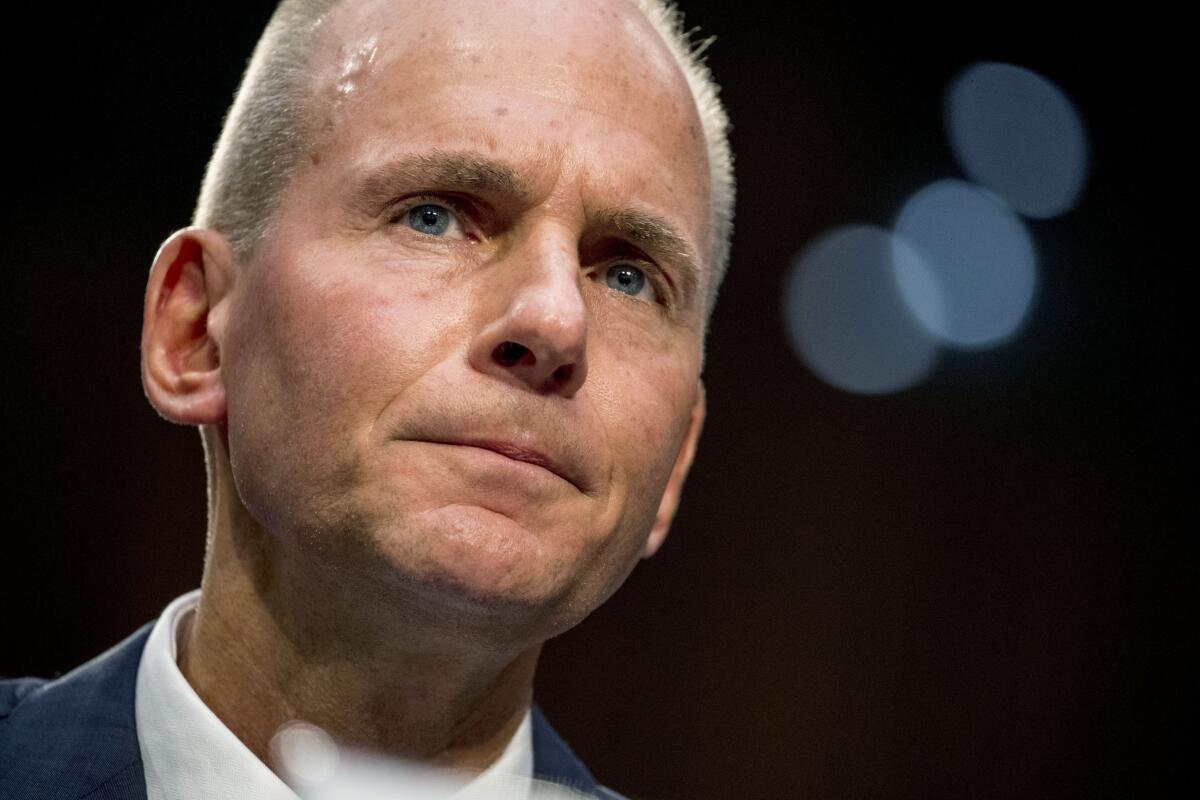

Boeing ousts CEO Dennis Muilenburg as 737 Max crisis drags on

- Share via

Dennis Muilenburg was ousted as chief executive of Boeing Co., a once-unthinkable turning point for a U.S. industrial champion now engulfed in turmoil after two deadly crashes of its top-selling 737 Max jetliner.

David Calhoun, a General Electric Co. veteran who had served as chairman since October, will replace Muilenburg as CEO and president on Jan. 13, Boeing announced Monday. The move followed a rare public rebuke this month by the Federal Aviation Administration. Just last week, Boeing said it would temporarily halt output of the Max, which has been grounded since March.

Boeing’s directors voted unanimously to install Calhoun, 62, as CEO during an emergency session Sunday, said a person close to the board. Chief Financial Officer Greg Smith will serve as interim CEO during the brief transition period, the company said. Director Larry Kellner, who once led Continental Airlines, will replace Calhoun as chairman.

Boeing is trying to regain its footing amid the Max grounding, one of the worst crises of the modern jet era. The plane maker’s reputation and finances have been battered after the Max disasters killed 346 people and prompted the worldwide grounding. Boeing’s design decisions and cozy relationship with the FAA are being scrutinized by Congress, and the Justice Department is conducting a criminal investigation.

“A change in leadership was necessary to restore confidence in the company moving forward as it works to repair relationships with regulators, customers, and all other stakeholders,” Boeing’s board said.

Boeing shares climbed 2.9% on Monday to $337.55.

Calhoun, a senior executive at Blackstone Group Inc., now faces the daunting task of extricating Boeing from one of the bleakest chapters in its 103-year history.

Boeing is turning to a GE veteran to run the company for the third time in less than two decades as it faces scrutiny for its unrelenting focus on shareholder value. The two CEOs who preceded Muilenburg — Jim McNerney and Harry Stonecipher — also rose through the ranks at GE while Jack Welch was chief executive there.

Calhoun had been in the running to lead Boeing almost 15 years ago, when directors instead selected McNerney. Calhoun ran GE’s aircraft engines division from 2000 through 2004 and ascended to the vice chairman role before leaving the company in 2006.

Affable and diplomatic, he’s also very connected. Calhoun serves on the Caterpillar Inc. board with Muilenburg and oversees Blackstone’s private equity portfolio.

He will serve as a “stabilizer” as Boeing works itself out of the Max crisis, said Richard Aboulafia, an aerospace analyst with Teal Group.

“There’s no doubt with Congress and regulators this is a lot better, and in the short run that matters a lot,” Aboulafia said.

But in the longer term, Boeing faces daunting product-development decisions — starting with whether or when to replace the 737 Max — that will be difficult for a company outsider with no engineering background, Aboulafia said.

A knock on Muilenburg, an aerospace engineer who spent his entire career at Boeing, was his lack of experience running commercial aircraft programs. The former Boeing CEO ascended through the defense division.

If his departure is classified as a retirement, Muilenburg’s exit package would be worth about $37 million at today’s share price and assuming target performance is achieved for outstanding awards, according to a Bloomberg estimate. That doesn’t include his defined benefit plan, which was valued at $13.2 million according to the company’s latest proxy filing. Muilenburg owns about $48 million of Boeing shares outright.

One of Calhoun’s first moves Monday was to reach out to FAA Administrator Steve Dickson to discuss the leadership transition at Boeing, said a person familiar with the call who wasn’t authorized to speak about it.

In an email, the agency said it expects Boeing to focus “on the quality and timeliness of data submittals for FAA review, as well as being transparent in its relationship with the FAA as safety regulator.”

Muilenburg’s departure caps an extraordinary fall from grace for an Iowa farmer’s son who had dreamed of turning Boeing into a globally admired corporate paragon, much as Welch did for GE. For two years as CEO, Muilenburg seemed to have the Midas touch. Then a brand-new Lion Air 737 Max plunged into the Java Sea on Oct. 29, 2018.

Although the plane’s design was largely set before Muilenburg became CEO, he bore responsibility for the company’s initial muted response — and the media firestorm that ensued when a second Max crashed in Ethiopia less than five months later. He would later describe the Max tragedies as the most difficult moments of a career spanning more than three decades, all at Boeing.

Muilenburg, 55, joined Boeing from Iowa State University as an intern in 1985. Over the next three decades, the aerospace engineer rose to increasingly prominent positions at the Chicago company’s defense business. As head of the division, he drove deep cuts to maintain profits when Pentagon spending was stagnant.

He succeeded McNerney as CEO in mid-2015 during the biggest sales boom in aviation history, fueled by low interest rates, readily available financing and the rapid expansion of low-cost airlines, particularly in Asia. Boeing’s 787 Dreamliner started generating cash months after Muilenburg took office, after a decade of losses. The plane, along with the highly profitable 737, funded the increasingly generous returns the company lavished on investors.

An avid cyclist fueled by diet Mountain Dew, the whip-thin Muilenburg brought an unapologetic, hard-charging edge to Boeing. “Compete to win” became a company mantra. He demanded deeper discounts from suppliers while creating new businesses that poached sales from its partners in everything from cockpit electronics to the mini jet engines housed in an aircraft’s tail.

The efforts helped turn Boeing into the most valuable U.S. industrial company, surpassing GE’s dimming star, as the plane maker’s market capitalization surged past $200 billion. Under Muilenburg, Boeing’s shares more than tripled through early 2019, far outpacing the broader market.

But the hard-nosed approach came back to haunt Boeing and its CEO. Responding to a preliminary accident report about the Lion Air crash, the company infuriated the carrier, one of its largest Max customers, by highlighting maintenance miscues on the doomed aircraft.

Boeing shocked pilots around the world when it revealed that an obscure flight-control subsystem known as the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, or MCAS, played a role in the accident.

Although the company had described MCAS to Max operators, it had removed references from flight-crew manuals. The Lion Air pilots had no knowledge of the system, which was tripped by an erroneous sensor reading and then shoved the plane’s nose down more than 20 times until they lost control.

Regulators worldwide began grounding the Max hours after the March crash of an Ethiopian Airlines jet, even as Boeing’s leaders and the FAA stood by the plane and recommended more investigation before taking action. In the aftermath, Muilenburg sent a message to employees saying he was “confident in the safety of the 737 Max.”

His tone changed over the following weeks and months. “We’ve learned from both of these accidents,” Muilenburg said in an interview in September. “We’re humbled, and learning, but we’re also confident. We know we have a great company with great people.”

It wasn’t enough.

Boeing’s problems snowballed as additional issues arose and regulators expanded their review of the Max beyond MCAS. There was the revelation that a cockpit light that might have alerted the crews to the sensor malfunction was inoperable in most Max jets because of a coding error. Although Boeing had known of the issue for more than a year, it didn’t alert the FAA or airlines until after the Lion Air crash.

As the grounding dragged on, Boeing faced the logistical challenge of storing hundreds of factory-fresh planes while keeping cash-strapped suppliers afloat. Fairly or not, the company’s laser focus on cash and costs reinforced a narrative that it had been lax on safety.

The leadership change was lauded by Michael Stumo, the father of Samya Stumo, who died in the crash of the Ethiopian Airlines jet March 10. She was the grandniece of consumer activist Ralph Nader.

Michael Stumo called the crash “preventable” and said Boeing now needs to clean house on its board.

“Mr. Muilenburg’s resignation is a good first step toward restoring Boeing to a company that focuses on safety and innovation,” Stumo said in a statement. “Now that it’s known what he and top Boeing officials knew, yet ignored, prior to the crashes, it has become clear how the company eroded in quality over the years.”

Johnsson and Clough write for Bloomberg.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.