Column: Wall Street Journal says the rich are fleeing California, but the flight is a trickle

- Share via

Solicitous as always of the downtrodden and sensitive to their burdens, the Wall Street Journal’s editorial board wrung its hands earlier this week over the impact of California’s income tax system on its residents. The Journal’s focus, naturally, was on those earning more than $5 million a year.

The point of the editorial, which was headlined “California’s Tax-the-Rich Boomerang,” was that the state’s ability to load ever-higher taxes on its wealthiest residents was coming to an end.

The basis of this argument was a recent paper by Joshua Rauh of Stanford’s Hoover Institution and Ryan Shyu finding that emigration of wealthy residents out of the state “spiked” after the implementation of Proposition 30 in 2012, which imposed a higher tax rate on incomes of more than $250,000, topping out at a 3% increase on incomes above $1 million (for married couples).

The liberal forecast in California always calls for higher taxes.

— Wall Street Journal

Including a 1% surcharge imposed on incomes over $1 million starting in 2004, this set the top marginal rate for them at 13.3%.

The Journal’s interpretation of the study was that “the likelihood of a wealthy resident moving out of California increased by about 40% after Prop. 30.”

Well, sorta. We’ll get to what the study actually says in a moment. The Journal went on to suggest that the flight of rich residents out of state means that during the next recession, the burden of California’s high-tax, high-service economy will fall on the middle class.

At least some of the $750 million the Resnicks are giving Caltech for environmental sustainability research derives from their unsustainable business practices.

The editorial also took the opportunity to level a blast at a referendum due to appear on next year’s November ballot aimed at amending Proposition 13 to raise property taxes on commercial property. “The liberal forecast in California always calls for higher taxes,” the Journal groused.

(Its editorial writers may not have noticed that commercial buildings can’t pick up and leave the state to avoid taxes, or that commercial properties have gotten a huge, unwarranted break under Proposition 13.)

The Journal implies that the phenomenon identified by Rauh and Shyu puts the lie to what it says is the liberal claim that raising taxes “has no effect on taxpayer migration and does no harm to state tax revenue.” Let’s start our counter-interpretation there. (I reached out to Rauh to see if the Journal’s interpretation squares with his own but haven’t heard back from him, although Shyu provided me with some useful insights about his and Rauh’s findings.)

To begin with, state revenues have generally been on the upswing since Proposition 30, reaching $143 billion in 2019-20. Much of the increase, according to the state budget, is “due to an improved outlook for personal income tax.”

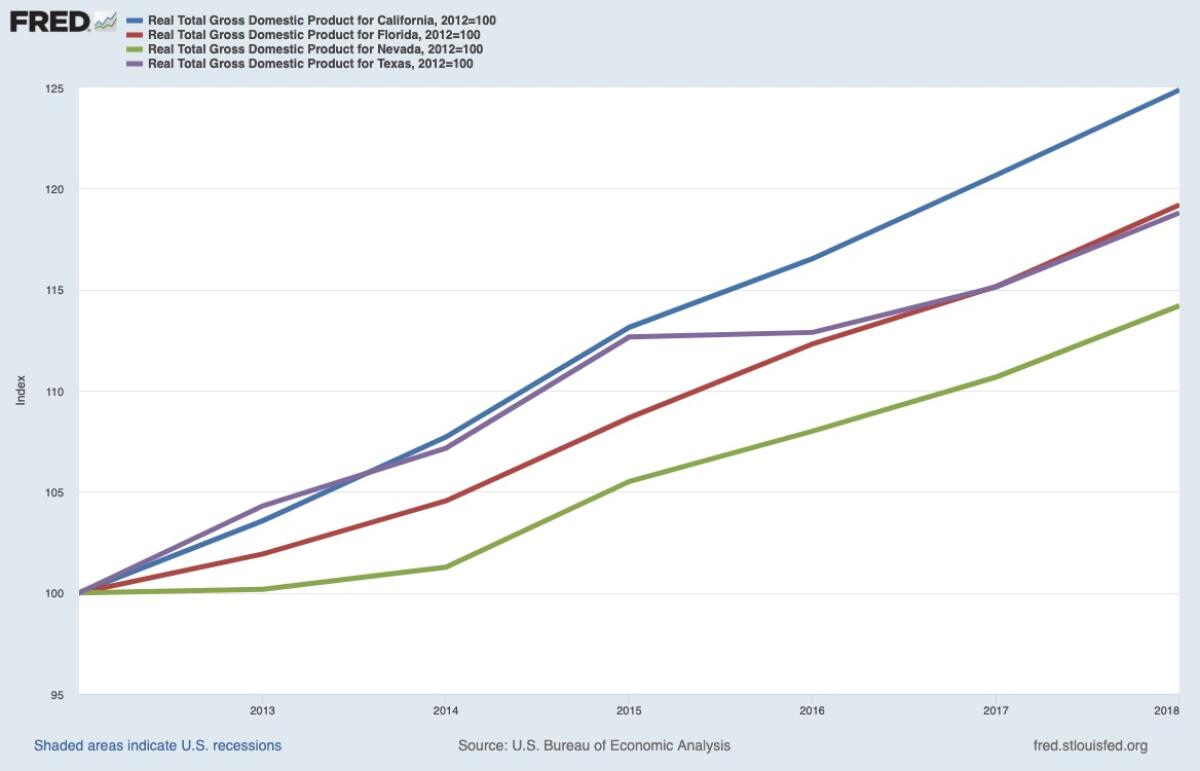

Since conservative voices like the Journal’s editorial page love to contrast California’s profligate spending ways with the records of low-tax states such as Florida, Nevada and Texas, it’s proper to note that California’s economy has grown much faster than theirs since 2012 — in fact, pretty much since the end of the recession in 2009.

What about tax-inspired emigration? Rauh and Shyu mined state tax records to identify the number of top-earning households that converted from California resident tax filers to non-resident filers. Most of the emigration, they said, represented taxpayers moving to states with no income tax, such as Florida.

They found that the rate of departures among households earning $5 million or more (thus subject to the top 13.3% tax rate) rose from 1.5% to 2.125% from 2012 to 2013, with a similar trend occurring among those with $2 million to $5 million in income.

This is the source of the Journal’s assertion that the rate of out-migration increased by about 40%. Yes, 2.125% is about 40% larger than 1.5%, but the Journal’s formulation makes it seem as though the migration turned into a torrent, while the basic figures make clear that the actual numbers are quite small.

A few years ago, the joke going around was that a cocaine habit was God’s way of saying you have too much money.

How many, exactly? Rauh and Shyu are a bit murky on this, but they do say that there were 66,936 tax filers paying the top marginal rate in 2012 — that is, single filers earning more than $500,000 and couples earning more than $1 million. Their calculations imply an “income-weighted increase in departures of 535 top-bracket taxpayers.”

Not all of those refugees ceased paying California income tax. Many still had California-sourced taxable income, for which they filed nonresident tax returns. Still, their state taxable income generally would shrink. Rauh and Shyu calculate that the behavioral response to the tax increase reduced the potential take from the increase by 45.2%.

A couple of points about this. Rauh and Shyu acknowledge that this sort of behavioral response to taxation is “an active topic” of inquiry among economists and, indeed, “an open question.”

As it happens, Charles Varner and Cristobal Young, colleagues of Rauh’s at Stanford, wrote in a recent paper that “it is clear that there is not a pattern of millionaire out-migration in recent years despite the 4-percentage-point increase on income above $1 million since 2004.” (Varner and Young worked with Allen Prohofsky of the state Franchise Tax Board; emphasis is in the original.) “If anything,” they add, “the trend has run counter to the tax-flight expectation.”

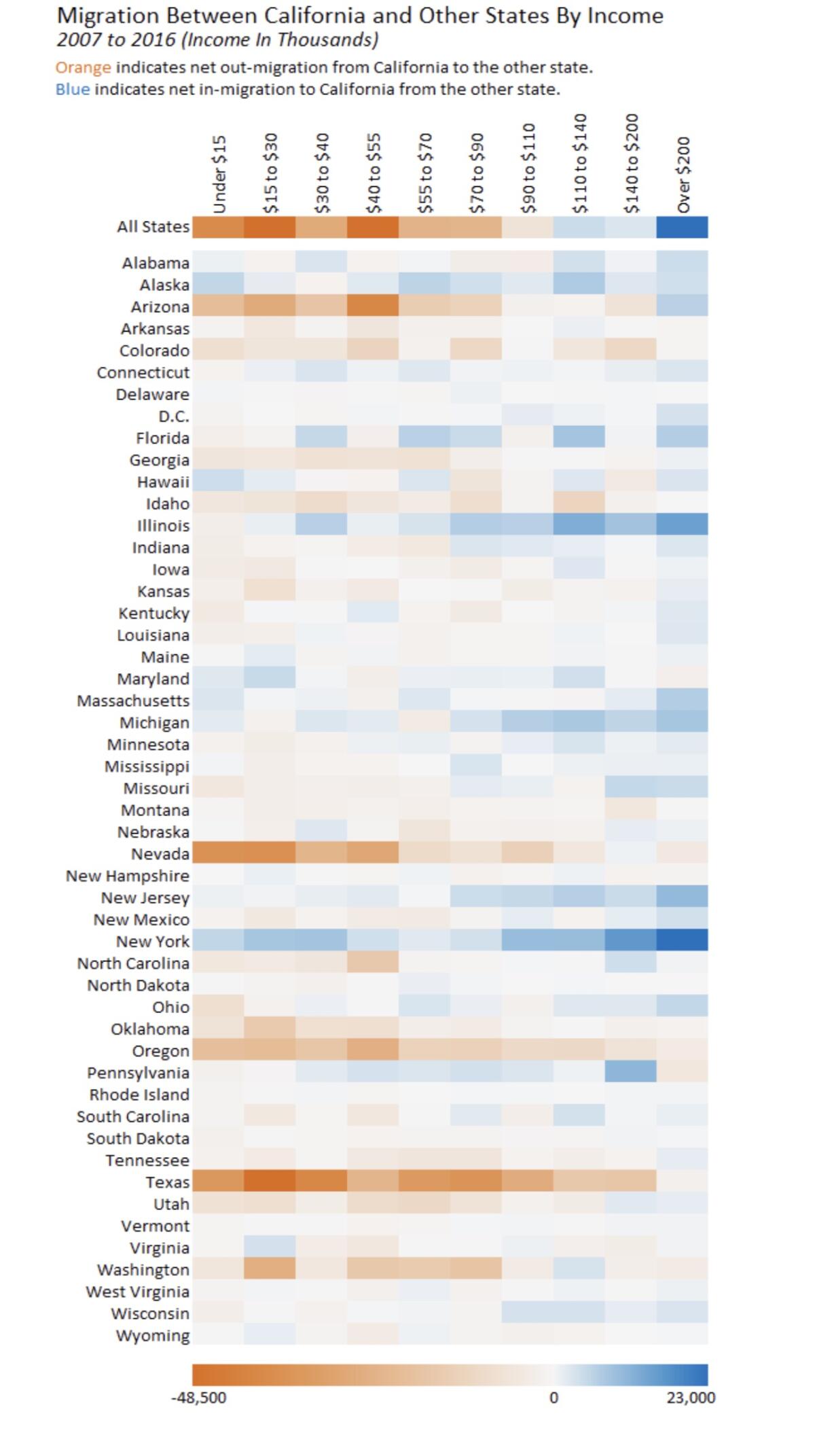

One difference between the two papers is that Varner and Young studied net migration, not simply outflow. As is well documented, California has been and remains a magnet for the young, the better-educated, and the affluent — all characteristics pointing to continued gains in income over time. As the Legislative Analysts Office has reported, the strongest net in-migration to California from other states occurs among those earning more than $200,000.

Varner and Young observe, moreover, that the population of millionaires is always extremely volatile. People become millionaires at a high rate, and millionaires become sub-millionaires at about the same rate. Most of the fluctuation, they say, is driven by “something other than migration,” such as business changes or divorces.

In any event, California probably is never going to be a tax haven for the rich. “Compared to states like Nevada, Texas or Florida,” they write, “California has had high taxes on the rich for some eight decades.” Nor is the current top marginal rate of 13.3% its highest ever — the top rate in California was 15% from 1935 to 1942, the era in which the great California boom began.

No one would claim that California’s economic growth will continue at its current rate forever. Yet something keeps drawing millionaires hither. Is it the weather, the style, or — for all that conservatives try to tag California as business-unfriendly — the opportunity to make millions?

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.