Column: California’s pot tax came in way below projections — and not for the reason you think

- Share via

As if to reinforce the idea that money is the most potent drug known to humankind, legislators in California and 10 other states have legalized marijuana, often with visions of a tax windfall dancing in their heads.

The fiscal gain may not have been the only rationale for legalization and in some cases not even the prime motivation, but it was never far beneath the surface. In California, proponents of legalization, who won their battle with the passage of Proposition 64 in 2016, predicted a tax windfall of $1 billion a year.

The actual figure for the fiscal year ended in June: $288 million. The forecast for the current fiscal year is $359 million. When, or whether, the tax will reach $1 billion is anyone’s guess.

When you drill down, the only hard fact is they seize a lot of plants.

— Jon Gettman, marijuana legalization promoter, in 2009

California isn’t the only state where expectations for turning marijuana into a cash cow have disappointed promoters. In Massachusetts, still the only eastern state with legalization on the books, the state Cannabis Control Commission projected a take of $63 million. The final tally for the last fiscal year was only about $30 million. The goal for the current year is $132 million, which would mean a quadrupling of income.

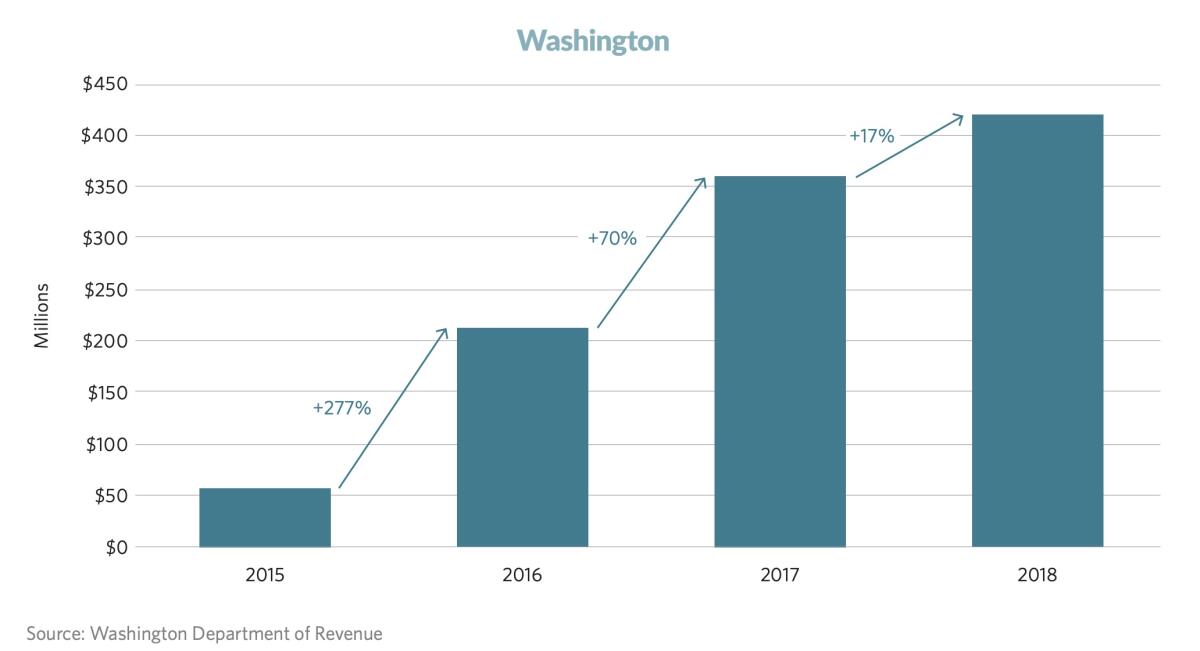

Even in states that met or exceeded their expectations, such as Colorado and Nevada, the rate of growth has been slowing. According to a recent survey by the Pew Charitable Trusts, marijuana tax collections in Colorado soared by 53% from 2015 to 2016, but only 18% from 2017 to 2018. Washington and Oregon also have seen a slackening in growth.

Experts have come up with numerous explanations for these disappointing results. They say the tax structures are overly complicated, the marijuana black market is still thriving, licensing of legal dispensaries is too slow.

Marijuana valuations in California are hallucinations

But there’s another explanation they’re avoiding. It’s one I highlighted back in 2009, when the legalization drive in California was gaining steam: From the start, projections of the size and value of the marijuana market itself, and therefore of the potential tax take, were based on fantasy.

As I wrote at the time, valuations of illicit activity, whether it’s drug sales, street crime or porn distribution, are notoriously squishy. Yet hard figures are accepted by the media as gospel, even though their sources are typically law enforcement agencies claiming to have achieved record-breaking drug busts or experts trying to pump up the importance of their chosen field of study.

In California, the inflation took the form of a dubious assertion that marijuana was the state’s most valuable cash crop. The assertion was duly reported in newspapers across the country, including this one, and was cited on CNN and NBC. The ostensibly hard valuation of the state’s marijuana crop was $14 billion, part of a nationwide marijuana trade worth more than $100 billion a year (including imports).

Yet this statistic was manifestly the product of a galaxy of magic asterisks. Its principal source was a 2006 study by Jon Gettman, a former president and national director of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, or NORML. I’ve reached out to Gettman via Shenandoah University of Virginia, where he’s on the criminal justice faculty, but haven’t heard back.

Gettman started with an estimate that U.S. domestic marijuana cultivation was 22 million pounds a year, although that figure, which came in 2003 from the George W. Bush White House, itself seemed to involve a dramatic and sudden increase from the government’s previous estimate of 7.7 million pounds.

The Justice Department again revised the estimate in 2007 to a range of 12.3 million to 20.7 million pounds, a uselessly wide range. The department evidently had added up the total amount of marijuana reported seized by law enforcement agencies and guessed that the cops had found only 30% to 50% of the total, but didn’t say how they reached that conclusion.

When we first examined the potential flashpoints between the incoming Trump administration and California, marijuana ranked fairly low on the list, below climate policy, immigration and Obamacare.

Gettman acknowledged that concrete information was exceedingly scarce — “When you drill down, the only hard fact is they seize a lot of plants,” he said.

Yet one wouldn’t have known how soft the “hard” facts really were from the debates that went on in statehouses across the country, where the taxable value of the marijuana trade was taken as read.

It’s true that there are sound policy reasons to legalize marijuana. Prohibition places a burden on all levels of government, including tens of billions of dollars a year squandered on arresting, trying and jailing sellers and users. Marijuana laws were unevenly enforced against blacks, youths and low-income defendants — the chances that a rich, white college student caught dealing to his dorm-mates would spend a night in jail, much less end up with a felony or misdemeanor count on his record, were effectively nil compared with the experience of a street-corner seller.

There are also sound arguments against legalization. These include the toll of drug abuse (not to say the abuse of alcohol and tobacco is not a significant social and medical problem). Legalization could put more money in the pockets of alcohol and tobacco companies, assuming they move into the cannabis market, for lobbying and political activity.

Yet by focusing on the potential tax gains from legalization, voters and legislators didn’t have to spend as much time weighing those difficult issues.

In California, where the $1 billion in annual revenue became a principal talking point for the Yes on 64 campaign, voters were inundated with promises of new funding for “afterschool programs that help kids stay in school; for job placement, job training, and mental health treatment; for drug prevention education for teens; to treat alcohol and drug addiction; and to fund training and research for law enforcement to crack down on impaired driving.” (Those promises came from the official voter guide for the 2016 election.)

Over 10 years, they were told, these programs would receive billions in revenues.

At the moment, these promises look like chimeras. But no one conversant with the history of ballot proposition campaigns or the uncertainties of government fiscal projections has a right to be surprised. Throw in the uncertainties of estimating the value of illicit or irregular activities, and the red flags should have been flying.

It’s possible, of course, that cannabis taxes will eventually fulfill the expectations set by their promoters, especially if some of those other obstacles, such as burdensome licensing of pot shops and the persistence of the black market, can be addressed.

But a billion dollars a year? Don’t start spending the money yet.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.