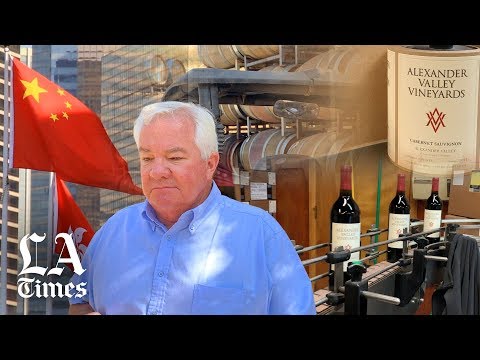

The latest casualty of Trump’s trade war with China? California wine

- Share via

HEALDSBURG, Calif. — Hank Wetzel’s vineyards stretch to the horizon, a swath of green straddling Sonoma County’s Russian River, farmed by generations of Wetzels for half a century.

It is a long way from Shanghai.

Nonetheless, seated outside his tasting room on a recent morning, the 68-year-old patriarch of Alexander Valley Vineyards was scrolling through photos from China on his tablet: A shot of his booth at a giant Shanghai trade show, thronged with customers. Another of Chinese restaurateurs sampling wines at a $1,000 dinner he hosted. And several of the pandas at Shanghai’s zoo.

When he began exporting to China two years ago, Wetzel had high hopes of penetrating its fast-growing imported wine market. But today, as President Trump’s trade war shows no sign of waning, “the economics of selling there are horrendous,” he said. “Our importer is keen on our wines, but every $15 bottle I sell her now ends up costing her $30. We could soon be out of business there.”

Since April 2018, in response to U.S. tariffs, China has slapped retaliatory taxes on $110 billion in U.S. imports — products as varied as electronics and soybeans. For wine, taxes and tariffs now amount to a 93% surcharge on every U.S. bottle. That’s double the amount on French wine, long favored by well-to-do Chinese. At the same time, wines from Australia and Chile, which recently signed free trade agreements with the Asian giant, are flooding into China, taxed at just 26%.

Global exporters view China as a barely tapped opportunity, given its exploding middle class and growing appetite for the quality and prestige of imported wine. The U.S. exported $1.46 billion in wine last year, 95% of it from California. China was the fifth-largest destination after the European Union, Canada, Hong Kong and Japan.

“China was our fastest-growing export market,” said Honore Comfort, vice president for international marketing at the Wine Institute, a San Francisco trade group. “We were heavily ramping up our activities there, adding restaurant promotions and cultivating relationships with key retailers.”

But U.S. wine exports to China were down by 33% in the first half of this year compared with the same period in 2017. As the trade conflict drags on, “Chinese importers will buy from a different country,” she predicted. “We’ve worked on building those relationships for two decades. Now all of that time is basically a loss.”

In an underground cave at Alexander Valley Vineyards, the air was cool and moist. Seven thousand oak barrels were stacked three high under the vaulted ceiling. Aging inside: a dozen varieties from Chardonnay to Zinfandel.

Outside the cave, a worker moved quickly across rows of barrels, siphoning wine through a glass tube from each of them, tasting for defects and spitting out each sample. Nearby, in a small warehouse, bottles moved along a conveyor belt as one machine after another filled them with Cabernet Sauvignon, corked them, sealed them with foil and slapped on labels before two women, working briskly, packed the finished product into cases.

Wetzel’s was among the first wineries established in Sonoma County and played a key role in establishing the Alexander Valley appellation. His wines, from Cyrus, a $65 Cabernet blend aged for 24 months, to Gewürz, a $15 wine made with organic grapes, have won national and international awards.

Over decades, Wetzel cultivated markets across California, in Texas and in other U.S. states to the point of shipping 175,000 cases last year. But he had never sought business abroad until he visited China two years ago. With his sons taking over day-to-day operations and sales, Wetzel and his wife, Linda, who oversees the winery’s bookkeeping, were looking for a new adventure.

“Twenty years from now, China could be the largest wine market in the world,” Wetzel said. “We want to be ready.”

At Shanghai’s trade show, they met Rose and Jack Sun, a young couple who operate Shindy Wine. “It was the kind of small operation I was looking for,” Wetzel recalled. “They had one Australian wine, one Chilean and one producer in France. I get more attention as their only U.S. wine.”

At the show, he was struck by the level of sophistication as hundreds of Chinese stopped by his booth. Although the vast majority of wine consumed in China is low-end domestic product, high-quality imports are gaining social cachet through social media and a savvy new breed of trained sommeliers.

Last fall, Wetzel hosted the Suns in Sonoma County. “We ate meals and drank wine for three days,” he said. “We showed them our harvest so they could go back to China and tell our story. We became friends.”

Alexander Valley Vineyards shipped just 750 cases to China last year — certainly no competition to large wineries such as Gallo and Mondavi, which have marketed there for decades. “The wine business moves slowly, like a turtle,” Wetzel said. “It takes a long time to build relationships.”

Preserving those connections takes continuous effort.

This week, he will embark on his third trip to Shanghai, for the opening of China’s first Costco, which has bought 250 cases of his wine. In June, while it was in transit, China imposed its latest tariff of 15%. Costco agreed to absorb half the increase, with the Suns taking the other half.

“There’s a dinner with Costco’s buyer,” Wetzel said. “I’m interested to see how they present the goods with these hefty prices.”

Wetzel also plans to travel with the Suns to Anhui, a province west of Shanghai, where they are opening a wine store. But with the trade war, “I expect to get an earful,” he said. “I hope this won’t be the end of our relationship, but the mood right now is pretty ugly. I don’t see how things could get much worse.”

Fellow exporters have been sharing the pain. “Even larger wineries that have traded for a number of years are extremely discouraged,” said Wetzel, who was elected board chairman of the Wine Institute in June. “They’ve lost a lot of business in the last six months.”

Dwight Bonewell, director of West Coast Wine Group in Napa, began exporting relatively inexpensive wine to China 12 years ago, sourcing grapes from the Central Valley. He sold his own brands and produced private-label wines for Chinese companies. With 20 distributors in China, Bonewell was on track to ship 43,000 cases this year.

“We thought we were going to have a banner year,” he said.

Now he expects to sell just 7,000, tallying his loss at about $1 million.

“The moment duties went up, many of our customers said, ‘We can buy, but you have to absorb the difference.’ But we can’t do that.”

Despite the setback, Bonewell said he expects his wine originally destined for China will sell in the U.S. market. “We are not giving up on China,” he said. “It is a huge market. We’ll wait for it to come back.”

When President Trump unveiled plans to launch a trade war with China early last year, Marisa Bedrosian Kosters, an executive at an Anaheim-based ceramic tile and stone retailer, sprang into action.

Wineries that export more expensive bottles have suffered less from the tariffs, as wealthier Chinese can better absorb the price increases.

“While our exports to China are off in volume, they are up over 30% in value year-to-date,” offsetting the tariff, said Ryan Stewart, director of international sales for Foley Family Wines in Santa Rosa, which owns vineyards in California, Oregon, Washington and New Zealand. “Our portfolio is more skewed to premium and luxury price points.”

Nonetheless, he added, “Several discussions with potential new import partners in China have been temporarily put on hold.”

At Wine Intelligence, a London consulting firm that tracks the global market, Chief Operating Officer Richard Halstead points to the “extraordinary amount of money” Australian and Chilean brands are spending to build China distribution. “They are squeezing out countries that don’t have favorable tariff regimes,” he said.

U.S. wine sales to China are a small target for a trade war, compared with motor vehicles, semiconductor components or soybeans — just 1.1 million cases last year out of 56.7 million cases that China imported globally. “But wine often gets involved in trade disputes because it has cultural symbolism,” Halstead said. “As China views it, it is about hitting a misbehaving trade partner where it hurts.”

In June, Trump took aim at French wine, complaining that it is allowed into the U.S. virtually tariff-free while France imposes duties on U.S. wine. “It’s not fair,” he told a television interviewer.

In Sonoma County, Wetzel said he voted for Trump because “he was a businessman…. But in the short term, these tariffs are not working.”

Meanwhile, he is taking the long view. “I’m going to see my importer with hat in hand,” he said. “I hate to think our investment is all dashed because of this trade war. But if it is, we’ll try again in five or 10 years. I hope this will pass sooner or later.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.