Column: California shows all states how to protect patients from Trump’s attacks on Obamacare

- Share via

Covered California, the state’s Affordable Care Act exchange, announced some good news a few weeks ago.

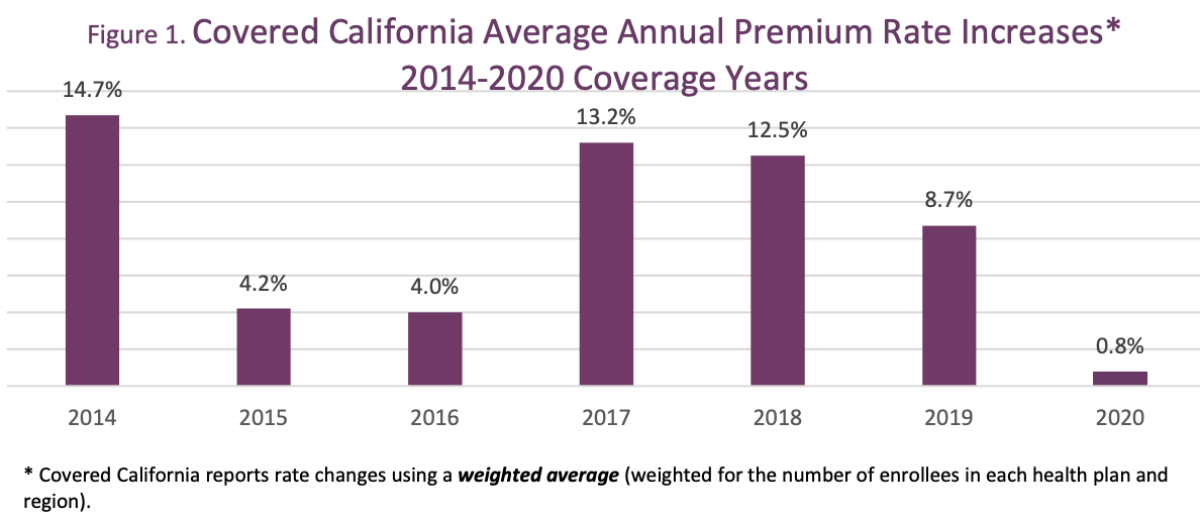

On July 19, the exchange said average premiums on its health plans would rise an average of 0.8% for 2020, the lowest annual increase in its history. In some regions, rates would increase even less or fall; customers who shop around when enrollment for 2020 plans opens on Oct. 15 could reduce their premiums by as much as 16.5%, depending on their home location, the exchange said.

For the individual market, the ACA was a complete game changer, and California went full in.

— Deborah Kelch, Insure the Uninsured Project

Meanwhile, three of the 11 insurers participating in the Covered California exchange, including giant Anthem, said they would expand their footprint in the state. As a result, the exchange said, more than 99% of Californians will be able to choose from two carriers or more for insurance in 2020.

Next year will also bring larger premium subsidies for most California ACA enrollees and — unique to the state — subsidies for households with income up to about $154,500 (for a family of four), compared to the $103,000 cutoff established by federal law.

The short-term health insurance pushed by Trump spends pennies on customers’ medical needs

This record shows not merely that a single state can protect the stability of its individual health insurance market in the face of determined sabotage at the federal level. It also shows other states how to do so, and teaches that investment in the ACA can pay for itself in lower premiums for residents, higher federal reimbursements, and lower overall healthcare spending.

Most of what California has done to keep its marketplace functional and stable is within the capability of any state. California expanded Medicaid (known in the state as Medi-Cal) under the ACA, taking advantage of the federal government’s 100% share of the expense from 2014 through 2016. The federal share is now 93%, and will drop to 90% for next year and beyond.

The state outlawed noncompliant insurance policies such as short-term plans, which rattled insurers and threatened to drive premiums higher by siphoning off younger, healthier customers seeking the cheaper rates that come from bare-bones benefits.

Covered California, meanwhile, negotiated the design and fees of health plans directly with insurance carriers so the plans would be standardized and the system easy for users to navigate. The exchange also aggressively promoted its individual plans with a marketing and outreach budget that reached $121 million in the current year, with the aim of enrolling the maximum percentage of eligible buyers. California’s uninsured rate fell to 7.7% in 2018, a drop of nearly 10 percentage points since the pre-Obamacare year 2013, nearly double the rate of decline in the nation as a whole.

“We used to refer to the individual market as the Wild West,” says Deborah Kelch, executive director of the Sacramento-based Insure the Uninsured Project. “There were no meaningful controls. For the individual market, the ACA was a complete game changer, and California went full in.”

California could not insulate itself entirely from the vicissitudes of the ACA market or President Trump’s campaign to sabotage the law. That campaign has included the promotion of bare-bones insurance plans, cutbacks in marketing and outreach, and constant threats to repeal the law.

After relatively modest premium increases of about 4% in 2015 and 2016, rates spiked by 13.2% in 2017. In part this reflected the end of a reinsurance program that had been designed to protect insurers from unexpected coverage costs only through 2016, when they were still feeling their way around the risk profile of a new, unfamiliar customer base.

Premiums rose by 12.5% in 2018, reflecting confusion over the ACA’s future created by congressional Republicans’ efforts to repeal the law and Trump’s numerous efforts to undermine its effectiveness.

California’s approach differs from that of other states that are rolling the ACA back, with the connivance of the Trump administration — for instance by imposing work rules and premiums on Medicaid or allowing insurers to sell limited-benefit health plans. These pound-foolish steps don’t even qualify as penny-wise, since they can end up costing a state more for less coverage.

But its approach aims to “signal to policy makers across the nation that you can build on and improve the ACA,” says Covered California Executive Director Peter V. Lee.

It has become obvious over the past few years that the Affordable Care Act has the power to cloud Republicans’ minds.

The state’s most important initiatives are aimed at insulating the state from federal policies undercutting the ACA.

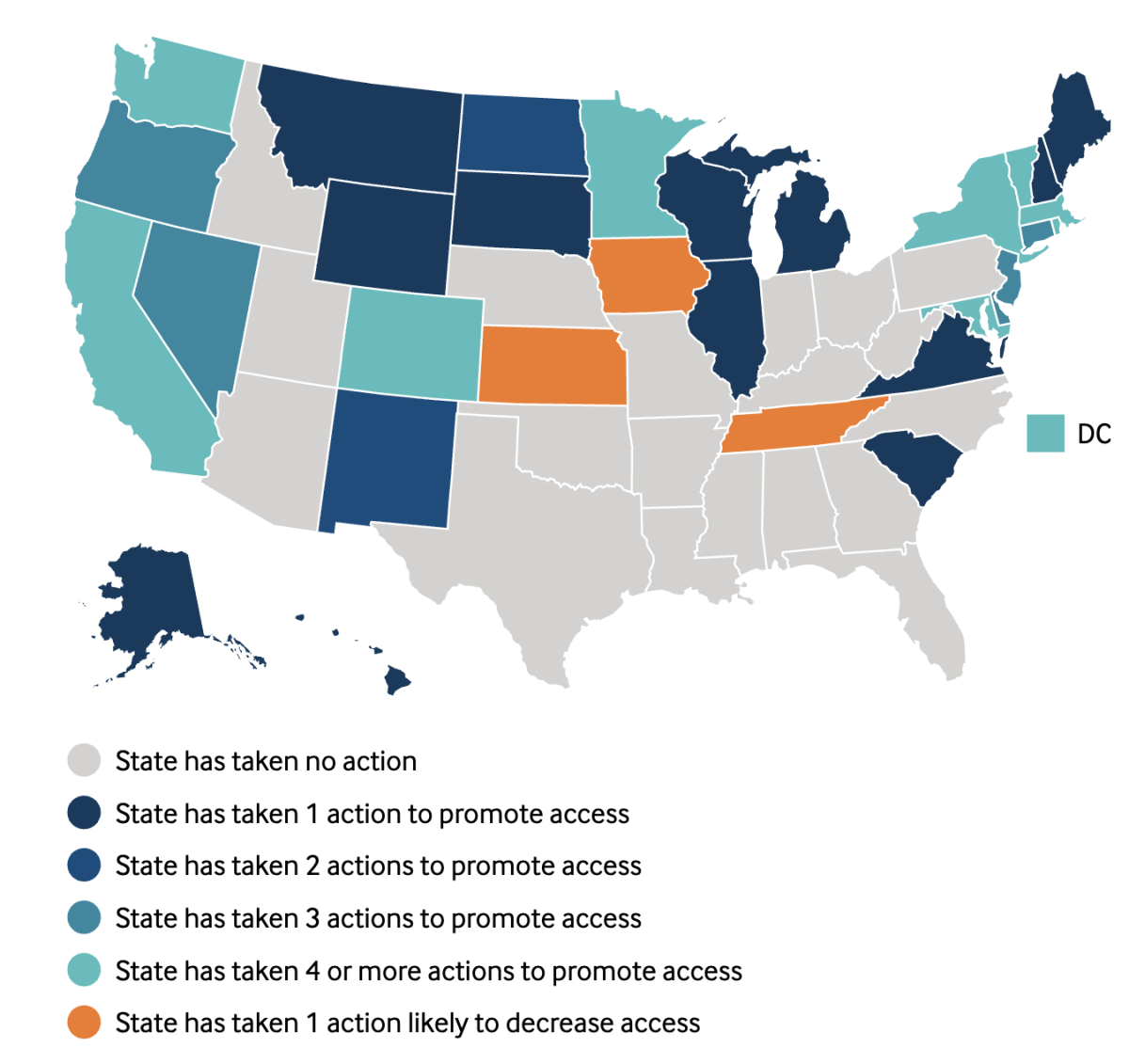

California is not alone in building a wall against the assault on the ACA by Trump and the GOP — 13 other states have enacted at least some provisions to stand their ground. But “California is clearly setting the pace for ACA preservation,” Obamacare expert Charles Gaba observed in June, after a session in which the Legislature enacted more than a dozen protective bills.

Consider the state’s rule on short-term insurance plans. These are junk insurance plans that evade the ACA’s consumer protections; among other features, they can reject applicants for preexisting conditions. Under the Obama administration, these plans were limited to three-month nonrenewable terms. Trump wants to allow them to be sold for terms of up to a year, with unlimited renewals.

Ever since Arkansas implemented its first-in-the-nation work requirements for Medicaid in June 2018, the state has functioned as a laboratory for the concept of placing unnecessary obstacles in the way of low-income people seeking health coverage.

In California, short-term plans were made illegal as of last Jan. 1, on the reasoning that individual buyers needing short-term coverage because they’ve lost a job or are changing employers can sign up for Covered California all year long instead of making do with inferior coverage.

Insurers aren’t blind to the state’s commitment to a stable marketplace. Blue Shield of California, which already offers standard health insurance through Covered Calfornia statewide, says it decided to expand its HMO to two additional counties from the current 24, partially in recognition of the “proactive steps the state Legislature is taking to support affordable coverage in California.”

The other expanding insurers are Anthem, which will expand from Northern California, Santa Clara County and the Central Valley into the Central Coast, parts of the Central Valley, Los Angeles County and the Inland Empire, and Chinese Community Health Plan, which will expand into all of San Mateo County.

The state’s most important initiatives were enacted earlier this year. These were the reinstatement of the individual penalty for not carrying insurance and an expansion of premium subsidies.

States that failed to expand Medicaid under the ACA suffered 16,000 unnecessary deaths

The first was a response to the reduction of the federal penalty to zero, a provision of the Republican-passed tax cut bill of December 2017. The ACA’s drafters had designed the penalty to raise the cost of going without insurance, thereby encouraging more young and healthy people to buy. The ACA’s drafters considered it a pillar of the law because that cohort generally has lower medical expenses, so their premiums help subsidize coverage for everyone else and moderate premiums.

The penalty removal, which was effective last Jan, 1, had a measurable impact on enrollment, experts have found. Covered California blamed its 24% drop in new enrollments for 2019 (by more than 92,000 enrollees) almost entirely on the penalty’s elimination. “Even robust marketing cannot offset the negative impact of its removal,” the exchange said.

“Bringing back the penalty is, in essence, playing defense,” Lee told me. “It’s saying that we will do everything we can in this state to counter federal policy.” The state penalty will match what the federal penalty was before Republicans zeroed it out — 2.5% of household income or $695 per adult, whichever is greater, with a family maximum of about $2,100. (That was done to keep matters simple “if the federal government comes to its senses and reinstates the penalty,” Lee says.)

Expanding the premium subsidy is a different case. That’s designed to rectify a known flaw in the Affordable Care Act itself. The act provides premium subsidies for households with income up to 400% of the federal poverty line, or up to $103,000 this year. For income above that, the subsidy drops instantly to zero in what’s known as the subsidy cliff.

These four charts trace the sudden improvement in health coverage for individuals in Obamacare

“The cliff at 400% is part of the original Affordable Care Act,” Lee says. “If, in the last six years of the Obama administration, Congress had been doing its job and talking about how to improve the law, we would have taken this up years ago. Instead, California is doing it now.” (Indeed, Hillary Clinton talked about making such a change during her presidential campaign.)

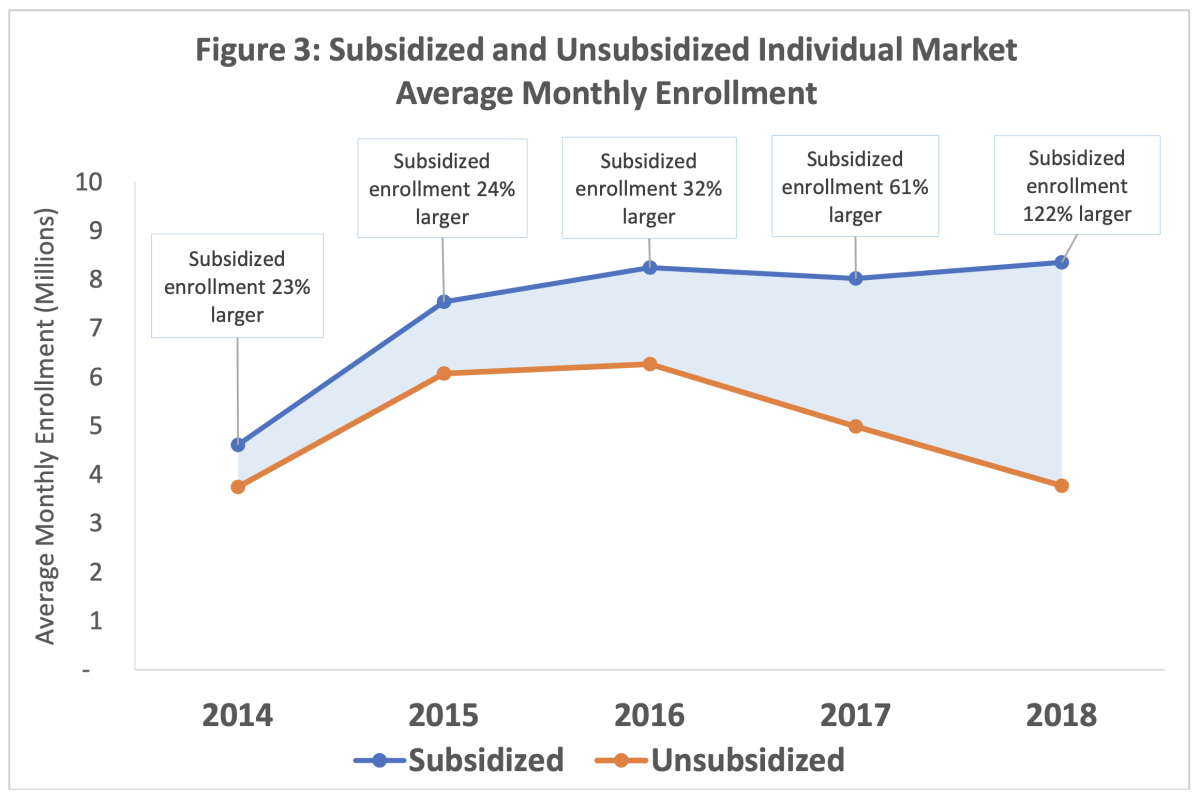

The state’s initiative will provide subsidies for households with income between 400% and 600% of the federal poverty level, or up to about $154,500 for a family of four this year. These are the people who feel left behind by the Affordable Care Act. They don’t get subsidies, so they’re fully exposed to every premium increase. And they’ve been abandoning the ACA system in droves — according to a new government report, unsubsidized enrollment fell by 2.5 million, or 40%, from 2016 through 2018. Expanding the subsidy will keep more of them insured.

The state also will augment the federal subsidy for households earning between 100% and 400% of the poverty line.

That will translate into an average subsidy of about $172 per month for households in the 400%-600% range, reducing their premiums by about 23%, according to the exchange. Buyers in the 200%-400% category will receive an additional $15 per household per month over the existing subsidy. Consumers earning less than 138% of the poverty level who enroll in Covered California rather than Medi-Cal will pay premiums of $1 per member per month.

Covered California expects these initiatives to produce about 187,000 new enrollments for next year, in part because customers will have to sign up through the exchange to get the subsidies rather than buying a plan separately. The subsidies will cost about $420 million in 2020, of which about $300 million would be offset by income from the penalty. But the gains would be felt more broadly — some 235,000 Californians with middle incomes will become eligible for premium subsidies for the first time and 687,000 others will become eligible for more assistance.

In short, California is showing that the best way for a state to fight the Trump administration is to stick to its own rules and regulations, based on solid evidence of what works and what’s right.

The campaign to bring affordable coverage to California residents may not be over. “These are tremendous steps forward,” says Laurel Lucia of the UC Berkeley Labor Center, “but there are still individual Californians who struggle to afford health plans.” Many are members of a largely overlooked group, families with incomes that place them just beyond the reach of premium subsidies.

“Covered California continues to be a leader in showing how a state marketplace can be effective,” says Gerald Kominski, a health policy expert at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health. “It’s a beacon for the rest of the country.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.