Q&A: How much pollution did VW’s emissions cheating create?

Here’s a look at how VW’s emission standards cheating might affect Californians.

- Share via

Volkswagen has admitted equipping half a million diesel cars in the U.S. with software to cheat on emissions tests — and then, in normal driving, to spew between 10 and 40 times the allowable levels of nitrogen oxides.

But how much pollution have the cars created since 2009, when VW first installed the so-called defeat devices? How much did public health suffer?

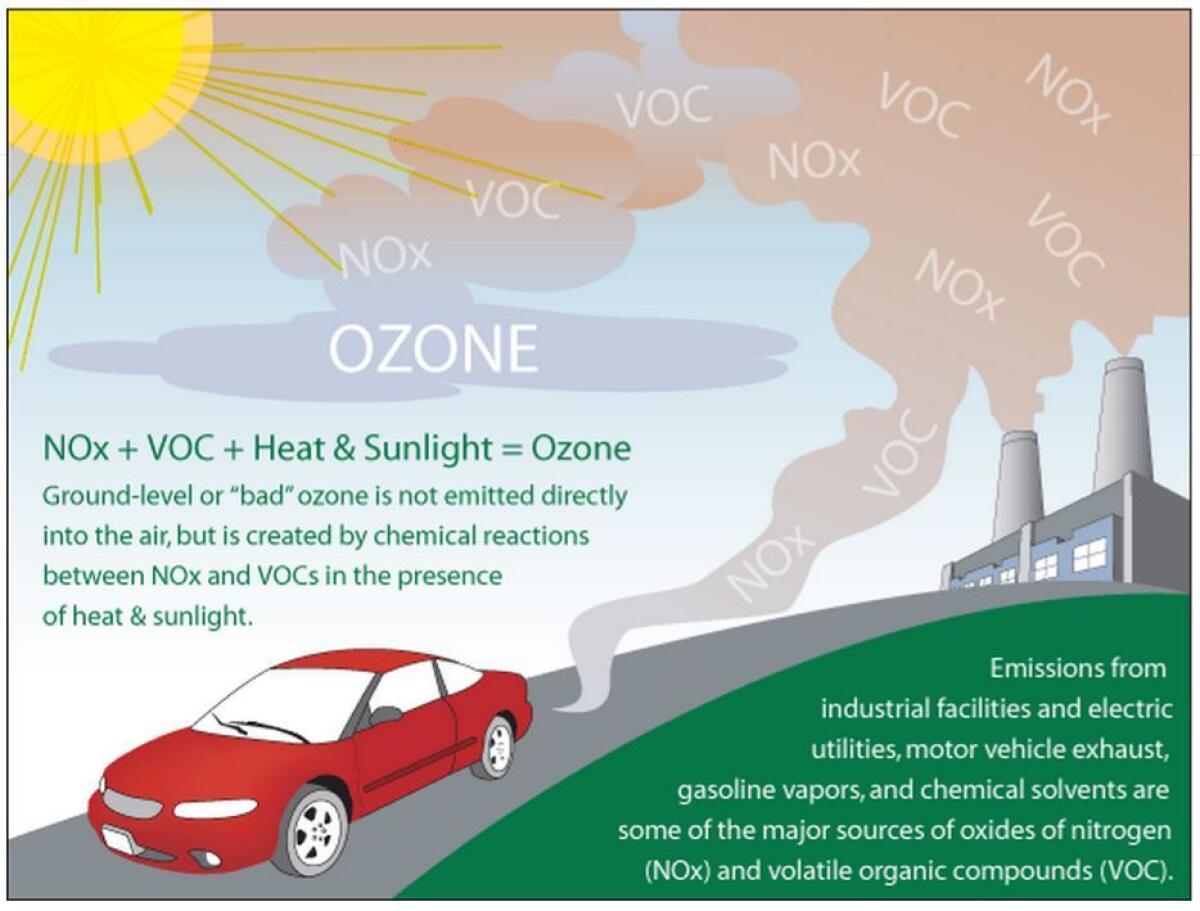

Nitrogen oxides are a class of chemicals that contribute to the formation of lung-damaging ozone, which has been linked to respiratory and cardiovascular ailments and to early deaths.

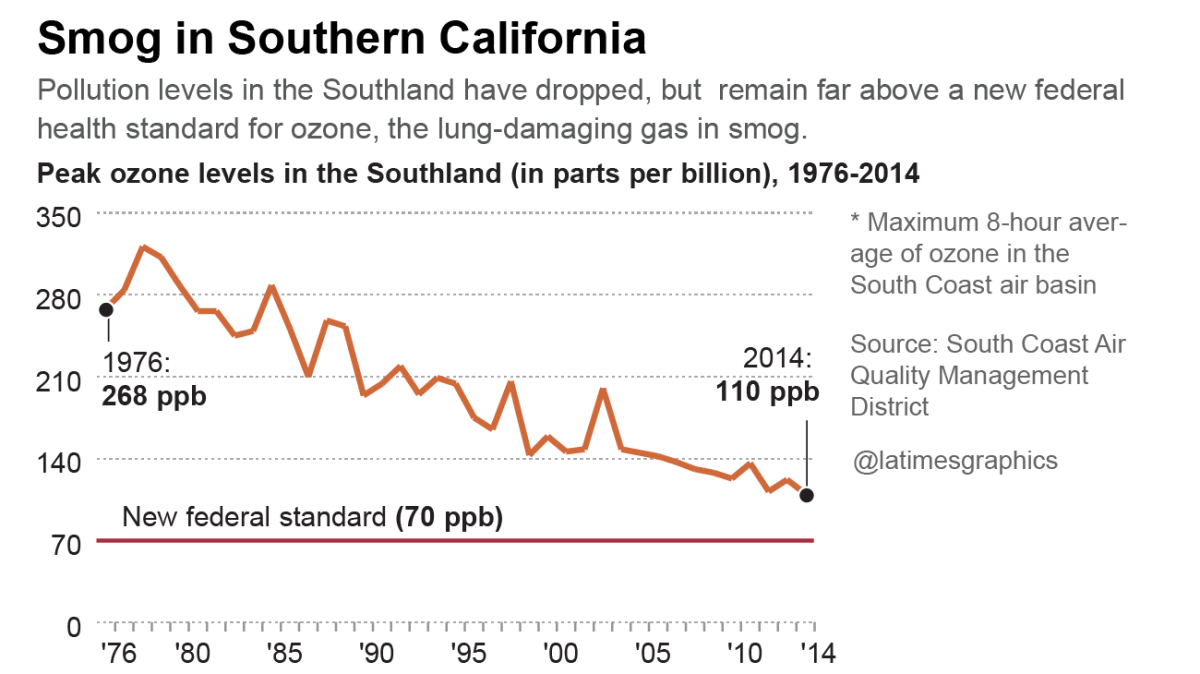

The added pollution is particularly relevant in Los Angeles, where ozone levels exceed federal limits. Many inland communities can experience more than 50 days per year with periods of excessive ozone, according to the South Coast Air Quality Management District.

Quantifying the extra pollution from thousands of VW diesels, over a span of seven model years, is a tricky business. California and federal regulators will use computer models to come up with some estimate on which to base penalties under the Clean Air Act.

That could take weeks, said Stanley Young, spokesman for the California Air Resources Board. “It’s not something we’re going to do on the back of an envelope,” Young said.

Until then, here’s what is known — and not known — about the emissions scandal’s impact on public health.

How much additional nitrogen oxides could have been emitted?

Regulators say the vehicles they tested emitted 10 to 40 times the permissible level of 70 milligrams per mile.

With nearly a half-million cars driving an average of 11,000 miles per year for nearly seven years, that could amount to anywhere from about 14,000 to 59,000 tons of additional nitrogen oxides.

California’s share, based on nearly 67,000 of the diesel cars, would be between 1,900 and 8,100 tons, while the greater Los Angeles area would have been burdened by 750 to 3,000 additional tons over nearly seven years.

These are rough guesses; real pollution levels would be affected by many variables.

Among the issues to be sorted out are the duration and range of emissions, Young said. “There has been a lot of talk that the exceedances are 10 to 40 times but there are specific characteristics as to when they’re very high and when they’re very low,” Young said. “It’s not like they’re 10 to 40 times all the time.”

At the lower end of that scale — 700 milligrams per mile — the VW diesels spewed seven milligrams above the average in-use rate for the existing U.S. passenger vehicle fleet. That includes scores of makes and models of varying age and maintenance. At the upper end — 2.8 grams per mile — they were about a third as dirty as the average for the current fleet of heavy-duty diesel trucks.

How much ozone was formed?

This will be a multimillion-dollar question for Volkswagen. But it may have different answers in different locations.

Ultraviolet radiation from the sun drives the chemical reactions between nitrogen oxides and other pollutants, producing ozone. Nitrogen oxides emitted in Nebraska on a cloudy winter day wouldn’t form as much ground-level ozone as the same amount from a tailpipe on a sunny summer day in Riverside.

“My gut feeling is, if we’re changing those nitrogen oxide inputs by this slight a degree … you would never notice it in ozone,” said atmospheric scientist Kent Hoekman, of the Desert Research Institute in Nevada.

Because nitrogen oxides are spewed into California’s air at a rate of about 2,106 tons a day from all sources, “even if it’s exceeding the standard by 40 times, that amounts to about 0.4% increase of this total inventory,” Hoekman said.

But because the Los Angeles basin is so far over its “carrying capacity” for such pollutants, even a small addition matters, said UC Riverside scientist Wayne Miller, a chemical engineer who has researched pollution in the Los Angeles basin for more than three decades.

Could these emissions have sickened or killed anyone?

Historically, it has been extremely difficult to link illnesses or deaths to pollution sources, not just because the science is complicated, but because people move around and are exposed to many other hazards. Epidemiologists, however, use statistical “incidence rates” that correlate pollutants with a relative risk of illness or early death, usually to quantify the effects of pollution regulation.

Based on rates used in EPA reports, one to six people could have died earlier than expected in the Los Angeles basin, with estimates varying depending on the model and the possible emission range of Volkswagen or Audi vehicles. The tally ranges from 2 to 16 early deaths in California and 12 to 112 nationwide.

That’s a lot of gray area, experts cautioned.

“In my view, using these risk factors to compute “body counts” is illegitimate, and comparing these computed body counts with actual deaths, such as from the recent GM ignition switch fatalities, is irresponsible,” Hoekman said.

Lyou agreed that such estimates can’t be used to calculate actual deaths, but he said they can add some context to estimates of the health impact.

Volkswagen has said that it has received no confirmed reports of any specific health effects linked to nitrogen oxide emissions from the vehicles in question.

“It is important for the public to know that, as the EPA has said, these vehicles do not present a safety hazard and remain safe and legal to drive,” Volkswagen Group of America CEO Michael Horn told a House subcommittee Thursday.

What are the raw numbers on VW’s 'cheat fleet'?

Number of diesel cars with illegal emissions

| U.S. | 468,802* |

|---|---|

| California | 66,979 |

| Greater Los Angeles | 26,816 |

Estimated tons of nitrogen oxides over legal limit (2009-2015)

| U.S. | 13,821 to 59,420 |

|---|---|

| California | 1,893 to 8,137 |

| Greater Los Angeles | 750 to 3,224 |

Sources: Kelley Blue Book, U.S. EPA, Energy Department, Times analysis

*Kelley Blue Book’s estimate differs from the 482,000 used by regulators because it’s based on registrations instead of sales.

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.