Trump says businesses can’t borrow because of Dodd-Frank. The numbers tell another story

- Share via

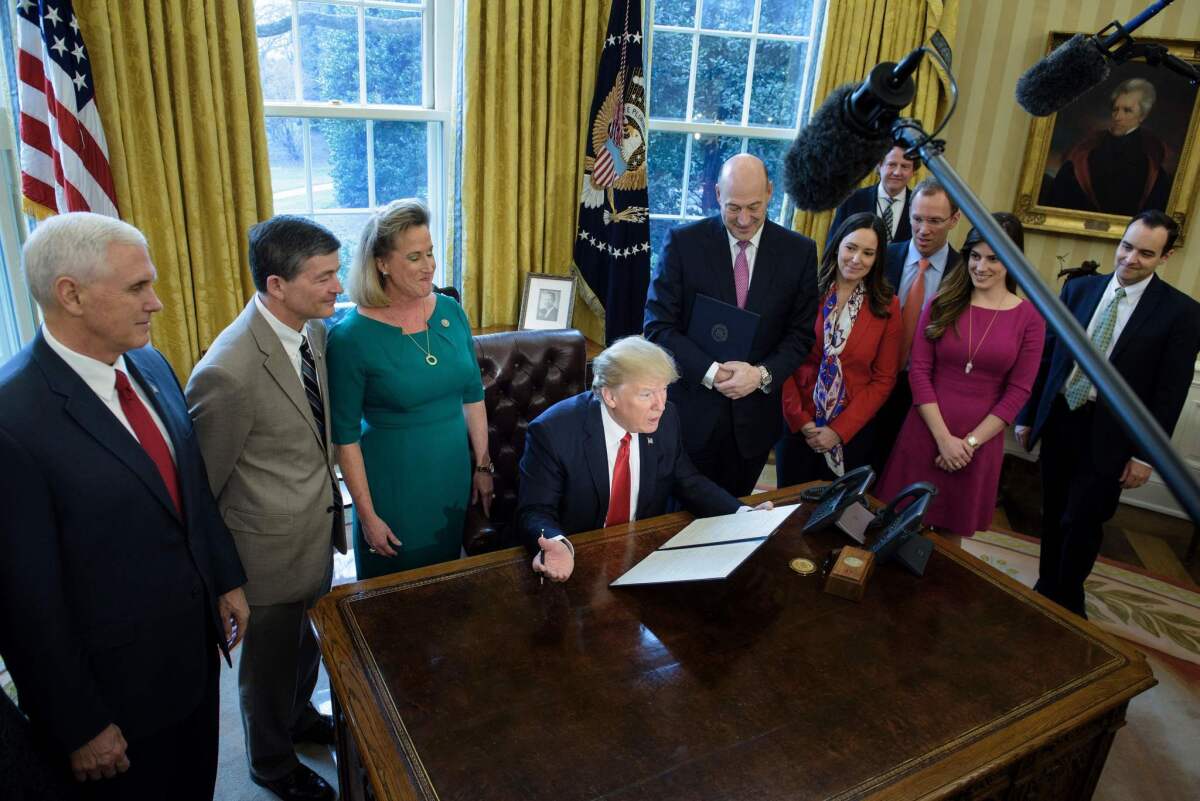

Reporting from Washington — President Trump was preparing the first step in a key campaign promise — dismantling the 2010 Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act — when he repeated a frequent criticism of the law.

“We expect to be cutting a lot out of Dodd-Frank because, frankly, I have so many people, friends of mine that had nice businesses, they can’t borrow money,” Trump told leading corporate chief executives, including Jamie Dimon of JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Larry Fink of money management giant BlackRock Inc., meeting at the White House earlier this month

“They just can’t get any money because the banks just won’t let them borrow it because of the rules and regulations in Dodd-Frank,” Trump said.

Shortly afterward, he ordered a wholesale review of the landmark act, which was passed in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

But a main reason for dismantling Dodd-Frank often cited by Trump and critics of the law — that its slew of tougher financial regulations have significantly restricted bank lending — isn’t borne out by the data.

Since hitting a post-crisis bottom in October 2010, commercial and industrial bank loans have increased 77%, according to the Federal Reserve. Few business owners say they are having trouble getting loans, surveys show. Household debt, including mortgages and auto and student loans, increased last year by the most in a decade, continuing a three-year upswing. And bank profits have been soaring.

“Nobody’s come up with really solid evidence that they can point to that bank lending over the last few years has been overly constrained,” said Fred Cannon, global director of research at investment bank KBW. “It certainly is not growing as fast as it was pre-crisis, but I’m not sure everyone wants no-doc, low-doc, non-verifiable lending again.”

Bankers, business people and industry representatives say the numbers don’t tell the whole story.

They say Dodd-Frank regulations have caused banks to be more careful about who they lend money to, extending loans only to the most qualified customers. Dealing with an onslaught of new rules has been particularly difficult for community banks — the first lenders small businesses turn to — contributing to a 15% decline in the number of those institutions since 2010 as they’ve closed or consolidated.

“A lot of the terms that have come from Dodd-Frank do not give us as much flexibility as we have had in the past to extend credit to our customers,’ said Jeffrey K. Ball, chief executive of Friendly Hills Bank in Whittier.

“Knowing my community and knowing my borrowers, I would love to be able to extend that credit,” he said. “But from a risk standpoint, it elevates the hurdles you have to clear.”

The law imposed some key new requirements on banks, including new mortgage rules if banks want to avoid future predatory-lending lawsuits.

Larger banks must undergo annual stress tests to determine if they could handle a sharp economic downturn, and prepare so-called living wills that lay out plans for safely shutting down if they were in danger of collapse. A restriction in Dodd-Frank known as the Volcker Rule prohibits federally insured institutions from trading for their own profit, while also limiting their ownership of risky investments.

And though lending overall has increased, banks have chosen to keep about $2 trillion in excess reserves at the Fed earning a low interest rate instead of using the money for loans because they say tighter lending requirements make it difficult to find borrowers.

Larry Stottlemyer said he’s felt the effects. He and his wife, Angie, have been trying unsuccessfully for six years to borrow about $2.5 million to expand their amusement park in Monrovia, Md.

They opened Adventure Park USA with an $8-million loan in 2004. Now they want to add a water park that would lead to the hiring of 50 to 65 additional summer workers, but have been turned down by small, medium and large banks, Stottlemyer said.

“We have more collateral now, our income’s up and we can afford a loan, but if it doesn’t fit in all the different nooks and crannies that the federal government has put in place since 2008, a small business can’t get money,” he said.

Stottlemyer said he could almost make the monthly payments on an expansion loan from his existing revenue but banks have told him he cannot count on any of the anticipated revenue from the water park.

“It’s not just me, I’ve heard it from a lot of my acquaintances in the industry,” he said. “They just cannot borrow money to expand.”

Business groups point to people such as Stottlemyer to argue that Dodd-Frank regulations need to be eased, particularly for community banks. And financial regulators, such as Fed Chairwoman Janet L. Yellen, said they’re trying to reduce the regulatory burdens on small banks, which don’t pose the same risks to the financial system as large banks.

Experts said some changes to Dodd-Frank could be helpful, but that its regulations, including tighter lending standards, have made the financial system safer.

“There’s no evidence that I know of that total lending has been crimped by regulation or capital requirements in particular, but there are pockets of the market where it is harder to get loans — and part of that is regulation and the reasons are good ones,” said Darrell Duffie, a finance professor at Stanford University.

“Regulators want banks to be a lot more careful, both in protecting borrowers from borrowing money they shouldn’t be borrowing and protecting banks from taking on too much risk,” he said.

Dodd-Frank was enacted under President Obama in 2010 with almost no Republican support. The law included tough new regulations on banks and other financial firms, set up a powerful panel of regulators to watch for signs of instability and created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to oversee credit cards, mortgages and other products.

Federal regulators later increased capital requirements for banks, particularly the largest ones, meaning they had to hold more money on their books in case of losses on their loans. And regulators created new restrictions for mortgage loans in order for lenders to be protected from predatory-lending legal challenges.

Despite strong complaints from the banking industry since the law was enacted, lending has been increasing steadily and bank profits are up, federal data show.

In the third quarter of last year, the most recent figures available, profits increased 13% from a year earlier to a record $45.6 billion, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

Loan balances increased 6.8% for the industry overall from the same quarter in 2015 and were up 9.4% at community banks, the FDIC said.

JPMorgan Chase, the nation’s largest bank by assets, reported a record $24.7 billion in profit last year, in part because of what a top executive called strong loan growth.

KBW’s Cannon said the higher capital requirements for U.S. banks has made them stronger than banks in Europe, where regulators weren’t as aggressive about tightening regulations in the aftermath of the crisis.

“You can actually argue Dodd-Frank was part of the more rapid restoration of health of the U.S. banking system than we saw elsewhere,” he said.

Surveys indicate that getting loans has not been a major problem for businesses. Only 4% of respondents in the National Federation of Independent Business’ January survey said all their borrowing needs were unmet, while 31% said all their credit needs were met. The rest mostly were not looking for loans.

“For the last four or five years, getting a loan hasn’t been a problem for our members,” said federation spokesman Jack Mozloom. He noted that the group’s members “tend to be older, better-established family businesses that have strong relationships with older banks.”

The National Small Business Assn. found similar results in its recent semiannual survey — 69% of respondents said they were able to obtain adequate financing in January. That was the same as in July but down from 73% a year earlier.

But not every business is looking to borrow money, particularly with sluggish economic growth, said association President Todd McCracken. If a business isn’t searching for a loan, then it would say adequate financing was available, he said.

The group would like to see changes to Dodd-Frank to ease the regulatory burden on community banks, McCracken said. “The sense of most people in the business community is Dodd-Frank didn’t get it right.”

Ball, of Friendly Hills Bank, said the law has caused the amount of money he spends on regulatory compliance to increase by 30%, to $300,000 a year — a big hit for a community bank with $150 million in assets. Loan growth has been about 2% to 3% annually, he said.

The bank, which opened in 2006, had hoped to expand into mortgage lending by now, but Dodd-Frank’s new mortgage rules have kept Friendly Hills from moving ahead, Ball said.

“The primary reason we do not do mortgages, even though our customers often ask for them, is because all the rules and restrictions are so strict we can’t afford to make a mistake,” he said.

Wayne Abernathy, executive vice president for financial institutions policy at the American Bankers Assn., said that although Dodd-Frank may not be cutting back overall lending volume, it has changed the nature of the loans that are made.

“Banks have continued to make loans, but they’ve been making loans to their best customers,” he said.

Banks lend because they need to do something with money that customers deposit. But banks also have about $2 trillion in excess reserves stashed at Fed banks that they would also like to lend but have not done so because of tougher regulatory standards for loans, Abernathy said.

Those reserves shot up from about $10 billion before the crisis but are down from a high of $2.8 trillion in 2014.

Cannon said there are changes that could be made to Dodd-Frank that would improve bank lending. They include subjecting only the largest banks — those with assets of more than $250 billion instead of those with more than $50 billion — to the toughest stress tests, and reducing some of the new requirements for mortgage paperwork.

A total dismantling of Dodd-Frank — as Trump has advocated — probably would boost lending in the short term, he said.

“But a wholesale repeal could put us back into the boom/bust cycle we experienced in the earlier part to the century,” Cannon said.

Follow @JimPuzzanghera on Twitter

ALSO

The U.S. labor force’s guy problem: Lots of men don’t have a job and aren’t looking for one

How Trump could use the presidency to help his own business interests

Are the president’s policies hurting the Trump hotels?

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.