Mojave’s thriving aerospace community spawns home-built airplane hobbyists

- Share via

Reporting from Mojave, California — By day, Justin Gillen works on a satellite-launching aircraft with a wingspan longer than a football field.

But in his spare time, the Scaled Composites project engineer tinkered for 2 ½ years with his hobby: a Tango 2 airplane, which isn’t much larger than an SUV. Now Gillen flies the plane — which he’s dubbed the Tango Time Machine — as far away as Oshkosh, Wis.

For the record:

2:30 p.m. Oct. 25, 2017An earlier version of this article said no home-built planes have flown in unlimited-class air races. There have been a few.

More than 40 years ago, legendary aerospace engineer Burt Rutan moved to Mojave to take advantage of the cheap land and open spaces.

Today, the company he founded, Scaled Composites, builds sleek and unconventional aircraft in hangars and facilities right in town. The hallway of the Mojave Air and Space Port is lined with photos of one of Rutan’s most iconic designs: the Voyager aircraft, which completed the first nonstop flight around the world without refueling.

Over the years, other aerospace firms followed Rutan into the desert. And the rising concentration of pilots and engineers spawned an unusual band of hobbyists: home-built airplane enthusiasts.

At least a dozen flight buffs flock to hangars on nights, weekends and during any spare moments to build full-scale airplanes, either from scratch or with parts provided in a kit. Some of the completed craft, many of them thousands of hours in the making, are used for air races or casual flying.

“The nice thing about Mojave is you can do anything you can think of,” Gillen said. “As long as you approach it from a reasonable safety aspect, nobody’s going to stop you.”

For Gillen, 37, plane building helped distinguish him as an engineer at Scaled Composites, provided a way to escape the desert — and gave him a side gig. Along with former Scaled co-worker Elliot Seguin, he is a test pilot for Wasabi Air Racing, a small firm started by Seguin and his wife that helps design, build and test experimental aircraft.

Gillen found the kit for his plane in the Experimental Aircraft Assn.’s Sport Aviation magazine. He liked that its fuel tanks could hold 57 gallons — other small planes can hold about 40 gallons.

The Tango is lightweight with a compact cockpit that has room for just two passengers. Its two doors are hinged to the roof and open like a simpler version of a DeLorean’s gull-wing doors. The only big modification Gillen made was to rebuild the engine.

The word “experimental” is emblazoned in bold, black letters on the bottom of the plane’s inner door frame, a designation required by the Federal Aviation Administration for amateur-built planes. Once certified by the FAA, these home-built, experimental planes can travel anywhere in the world.

Scaling up

Matt Stinemetze and his brother, Justin, caught the flying bug from their father.

Growing up, the two siblings were surrounded by airplane books, airplane magazines and airplane models. Stinemetze still remembers when his father took him to the hobby shop at age 7 to buy a Revell SnapTite model kit of the Space Shuttle Enterprise — the first of many models he would complete over the years, ranging from plastic and balsa wood to remote-controlled.

“I was the kid in class getting in trouble because I was drawing airplanes,” he said.

Stinemetze decided while in high school that he wanted to become an engineer so he could work on the real deal. Today he is chief engineer at Scaled Composites.

In 2003, he bought a partially completed Long-EZ aircraft — a Rutan design known for its canard layout, with a short wing toward the front of the fuselage and a longer wing toward the back. For years, the Rutan Aircraft Factory sold plans for this plane and other Rutan designs so home builders could assemble the airplanes themselves. The manufacturer stopped in 1985, though, and today Long-EZ blueprints are hard to find.

Stinemetze put about 2,000 hours of work into the Long-EZ, adding new avionics and substituting a 160-horsepower engine for the 110-hp one that came standard. He also built from scratch his own landing gear and side pods that can each haul up to 50 pounds of baggage.

That’s come in handy when he and his wife Kit fly the plane 1,000 miles nonstop to visit their parents in Kansas.

Now Stinemetze, 42, and his brother Justin — who is just 11 months younger and also works at Scaled as a crew chief — are working in a Mojave hangar on a new project: a pair of two-thirds-scale replicas of the F8F Bearcat, a powerful single-engine U.S. Navy fighter that arrived just as World War II ended.

The Stinemetzes are building every part of the plane from scratch, down to the wheels.

“It was the last great propeller airplane,” Matt Stinemetze said. “If you’re going to build a replica of something from scratch, why not pick the best one ever?”

Finishing the race

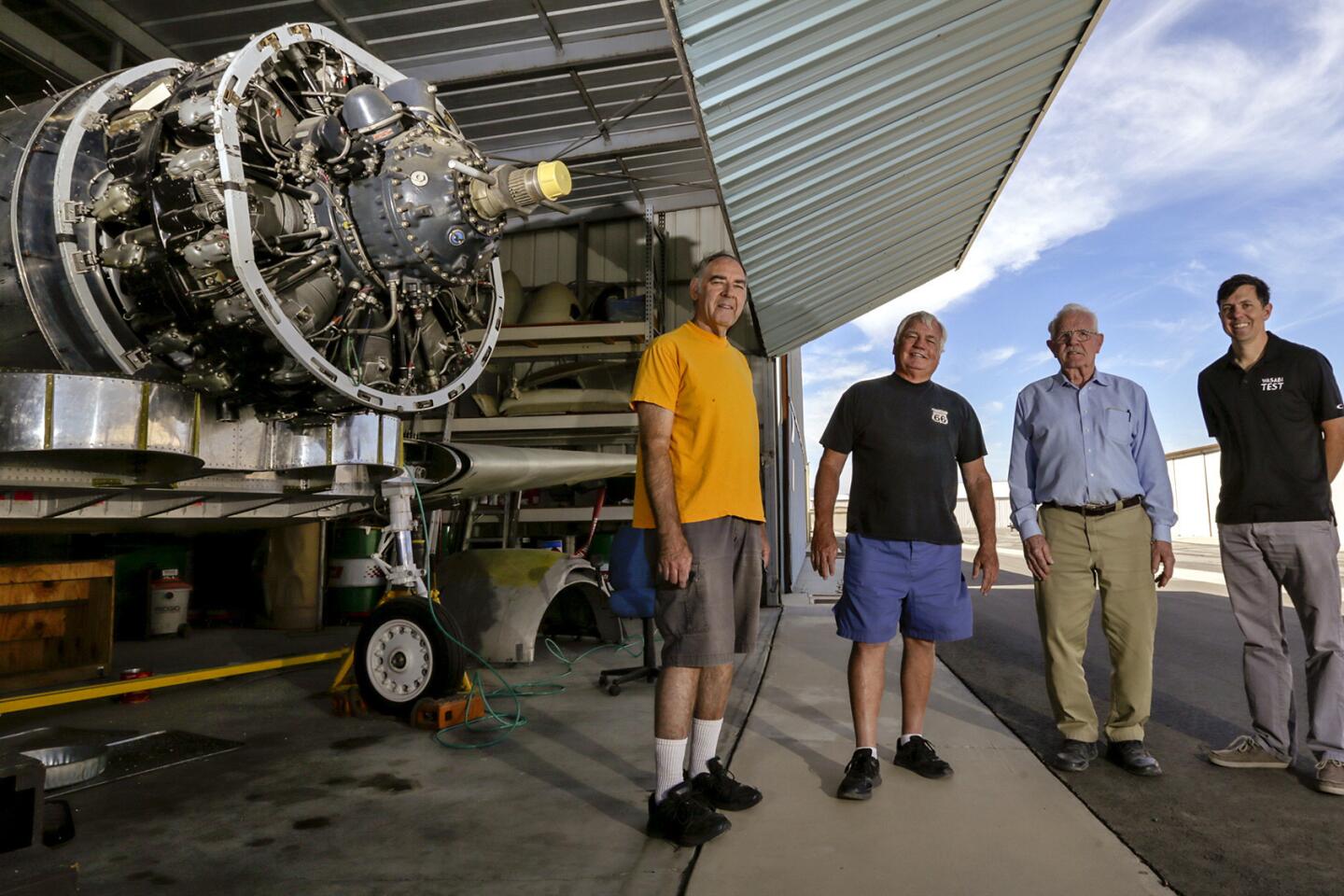

One of the Mojave hangars houses a hulking grey plane that was the brainchild of a former Lockheed engineer who holds seven aircraft design patents — and has been 42 years in the making.

William H. Statler first dreamed up the plane’s design. He died in 2005. Now his sons and a handful of other dedicated volunteers are close to finishing it up in his memory.

“It’s something we wanted to do,” said his son, Bill Statler, 75, who began the home-built project with his father in 1975. His own aerospace engineering career included time at Lockheed’s Skunk Works and on Northrop’s B-2 stealth bomber program.

The elder Statler got into home-building in the early 1950s, helping people build small racing planes known as Goodyear racers. His young son would often accompany him to races or to those people’s homes and it “got into my blood as well,” Statler said.

Father, son and a friend set about building a light, fast air racer to compete in the “unlimited” class, where there are just a few rules. The aircraft must be piston-powered and propeller-driven, weigh at least 5,200 pounds and fly at a minimum of 275 mph. Up to nine planes race around an 8.2-mile oval course marked by 55-gallon drums set on telephone poles. The planes must stay at least 50 feet off the ground, though some pilots still find sagebrush in their wing tips after a race.

The elder Statler wanted to build a plane entirely from scratch to show that less-expensive home-built planes could compete with the refurbished WWII fighters that dominated the races. The plane would be one of a very few home-built aircraft to fly in the unlimited class.

The now five-person team has pieced together parts from other planes, including landing gear from a T-6 trainer aircraft, and thin wheels and brakes from a private jet. The massive plane is powered by a WWII-vintage Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engine.

Statler, who drives up to Mojave on Saturdays from Santa Clarita, estimates the project has eaten up $200,000 over the years. He hopes to race it at next September’s renowned Reno air races.

“It’s one of those things you get into and you think, ‘What have I done?’” Statler said. “But it’s fun.”

From hobby to career

Ralph Wise was a Marine F-4 pilot in Vietnam when he caught the home-built plane bug.

Wise read an article in Air Progress magazine about small Formula One race planes. Intrigued, he selected the speediest one and mailed in an order to the manufacturer for blueprints.

Once back from Vietnam, he bought an engine, some tires, a propeller and fabricated the rest of the parts to put together the so-called tube-and-fabric plane with a wooden wing in 10 months.

“I was a bachelor,” Wise recalls. “I had nothing else to do.”

Over the years, Wise would go on to build six more planes, including a seaplane and several other racers. Some were clean-sheet designs he created entirely from scratch. Others were from kits.

Not all flew well. A seaplane he built from a kit came close to sinking in a Northern California lake when the plane’s tail broke off on landing. The pilot barely got it back to shore.

Today, Wise, 75, has only one complete plane left — his seventh, a two-seater nicknamed Snort that took 10 years and 10,000 hours to design and build. It’s housed in one of Wise’s three hangars at the Mojave Air and Space Port while he completes an annual inspection.

His early experience with home-building helped him start a business in aircraft modification at the Camarillo Airport after he left the Marine Corps. That led to a subsequent job with a Mojave project manufacturer, who was helping the company now known as BAE Systems convert F-106 manned aircraft into drones.

Wise, a Lancaster resident, now owns his own small shop in Mojave called GT Aero that contracts with BAE. He also helps Statler with his home-built plane.

“You have to be motivated,” Wise said of home building. “Once you lose the motivation, everything comes to a halt.”

Twitter: @smasunaga

ALSO:

Lockheed joins Boeing and General Dynamics in betting on ocean drones

Caltech opens a drone lab, with big ideas to improve how robots work with humans

Google parent company sends up solar-powered balloons to bring internet service to Puerto Rico

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.