How will L.A. replace three gas plants that Mayor Eric Garcetti plans to shut down?

- Share via

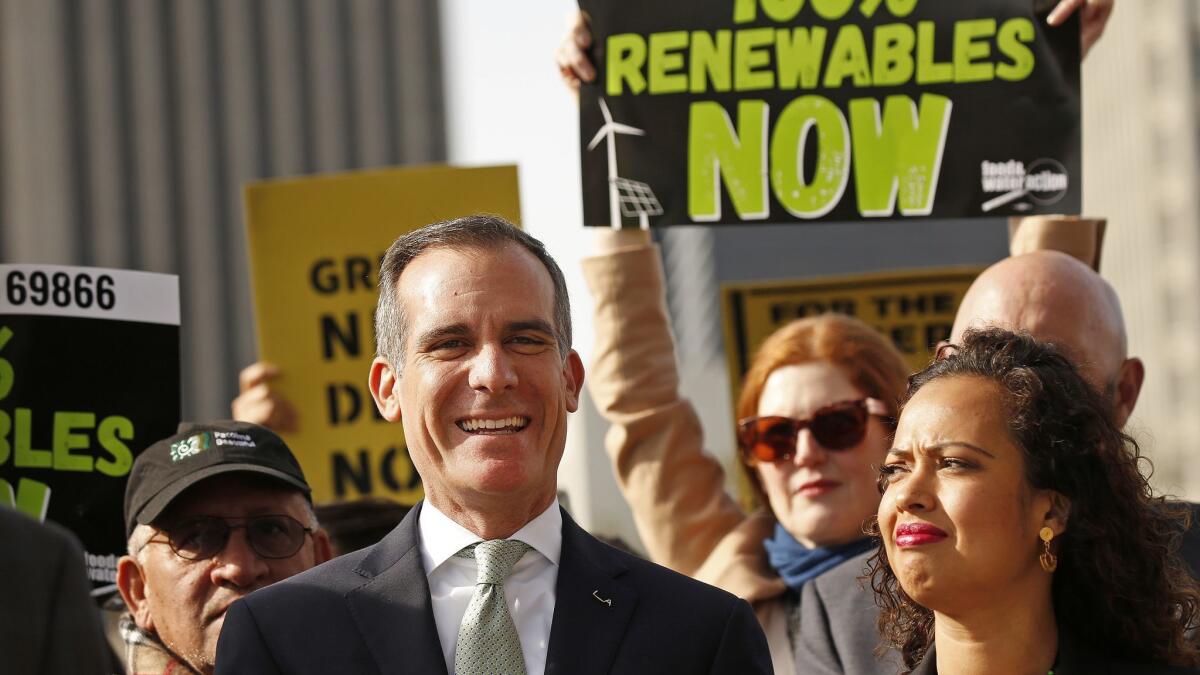

Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti thrilled environmentalists and public health advocates with his announcement that the Department of Water and Power won’t spend billions of dollars rebuilding three gas-fired power plants along the coast.

But now the hard work starts: figuring out how to replace the three facilities without raising energy prices or increasing the risk of power outages. And another battle looms on the horizon, as Los Angeles moves forward with plans for a new gas facility in Utah to replace a coal-fired power plant that still generates much of the city’s electricity.

City officials and activists who have pushed Los Angeles to take more aggressive steps to tackle climate change hailed Garcetti’s decision to stop DWP from making life-extending investments at the Scattergood, Haynes and Harbor gas plants. At a news conference Tuesday, the mayor cast his move as part of a global struggle to rein in the carbon emissions that are heating the planet, and as a major step toward removing fossil fuels from the power mix of the nation’s second-largest city.

“We often wonder, what does history look like, what does it feel like? It feels like this, today,” Garcetti said. “A moment in which all of us as human beings are challenged to step up and to lead in a moment that will define our lives, and the lives of our children, and our children’s children.”

Natural gas accounted for 31% of the city’s power supply in 2017, with much of that generation coming from Scattergood, Haynes and Harbor. DWP managers had argued in recent months that those three facilities in particular are critical to keeping the lights on for the city’s 4 million residents, especially on hot summer days with the highest electricity demand and during outages elsewhere on the power grid.

Los Angeles is under state orders to shutter all 10 gas-fired generators at the three plants in the coming years because they use ocean water for cooling, which can harm marine life. DWP officials had said they weren’t sure clean technologies like batteries would be cheap or effective enough to replace the gas plants before the state’s deadlines, 2024 for Scattergood and 2029 for Harbor and Haynes.

On Tuesday, they sang a different tune.

“The question that staff has somehow heard for a number of years is, ‘Can we?’ And I don’t think ‘can we?’ is the right word. It’s ‘How can we?’” DWP General Manager David Wright said. “Some of the best managers and the best engineers, planners and operators will take this challenge and will make it work.”

The department may try to buy itself some extra time on one of the gas plants. Nancy Sutley, the utility’s chief sustainability officer, said at a board meeting Tuesday that DWP staff could ask the State Water Resources Control Board to extend the deadline to shut down Scattergood to 2029, if the DWP board approves.

Los Angeles isn’t alone in trying to eliminate fossil fuels: California lawmakers passed a bill last year requiring the state to get 100% of its electricity from climate-friendly sources by 2045. The main challenge is that the two cheapest and most popular sources of renewable energy, solar and wind power, are intermittent, generating electricity only when the sun shines or the wind blows.

That’s starting to change as lithium-ion batteries and other forms of energy storage get cheaper, making it possible to bank electricity from solar panels and wind turbines in increasingly large quantities. But some critics still question whether it’s possible to run an affordable, reliable power grid without fossil fuels anytime soon.

Kendal Asuncion, a public policy manager for the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce, pointed to the recommendations of a team of DWP consultants who had advised the utility to rebuild seven of the 10 ocean-cooled gas units. Asuncion said the city’s environmental goals must be “balanced with resiliency, responsibility and financial responsibility” to keep power flowing smoothly and electricity rates low.

“Businesses are concerned about these impacts to our bottom line, and we’re concerned that there was no ratepayer advocate report or analysis done on this,” Asuncion said at Tuesday’s board meeting.

It’s hard to predict whether battery costs will keep falling, or what other clean energy technologies and strategies will evolve over the next decade. But there’s a growing body of scientific literature suggesting that eliminating fossil fuels is doable. Just last month, researchers from Finland and Brazil released a study finding that powering the Americas with 100% renewable energy may actually reduce electricity costs.

As Los Angeles officials celebrated the transition away from natural gas on Tuesday, they mostly glossed over the fact that the city still gets much of its power from an even dirtier fossil fuel: coal. In 2017, 18% of L.A.’s electricity was generated at the Intermountain Power Plant, a coal-burning facility outside Delta, Utah.

That plant supplies energy to dozens of cities and power agencies in California and Utah, and is scheduled to be decommissioned by 2025. But the DWP, which buys nearly half the electricity generated at Intermountain, supports a plan backed by other Intermountain buyers to replace the facility with an 840-megawatt gas plant — the same type of power plant Garcetti wants to retire here in the Los Angeles Basin.

Asked about DWP’s support for a new gas plant in Utah, Garcetti described it as “part of a plan to get off of coal.” But he acknowledged that any new investment in fossil fuels “doesn’t sit easy, I think, with any of us.”

“We have to make sure that there is sustainable power, and it’s way too early to be able to say there’s something where we can snap our fingers and have battery storage at that level,” Garcetti said. “It’s something that I continue to push this department to look at in any way that we can. Because that to me is not a long-term solution. I don’t want to see in 30 years from now that we have a natural gas plant, even if it’s in Utah.”

DWP officials have said they agreed to a gas plant at the Intermountain site in part to maintain access to the Southern Transmission System, a 500-mile power line corridor that brings electricity from Utah to Southern California. They see the transmission lines as a valuable pathway for importing low-cost clean energy from Utah alongside the gas-fired electricity. They’ve also said they plan to pay down the gas plant’s costs on an accelerated schedule, to make possible its early retirement.

But S. David Freeman, a former DWP general manager who now works with environmental groups to advocate for renewable energy, has criticized Garcetti for going along with the Utah gas plant — even though the mayor helped downsize the project to 840 megawatts from the 1,200 megawatts previously supported by DWP.

“It’s global warming, for God’s sake. It doesn’t matter if it’s in Utah or if it’s in downtown L.A. as far as the climate’s concerned,” Freeman said. “I think a little sunlight needs to be shone on that sucker.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.