How do you shut down a failing financial giant? Lawmakers can’t seem to agree

- Share via

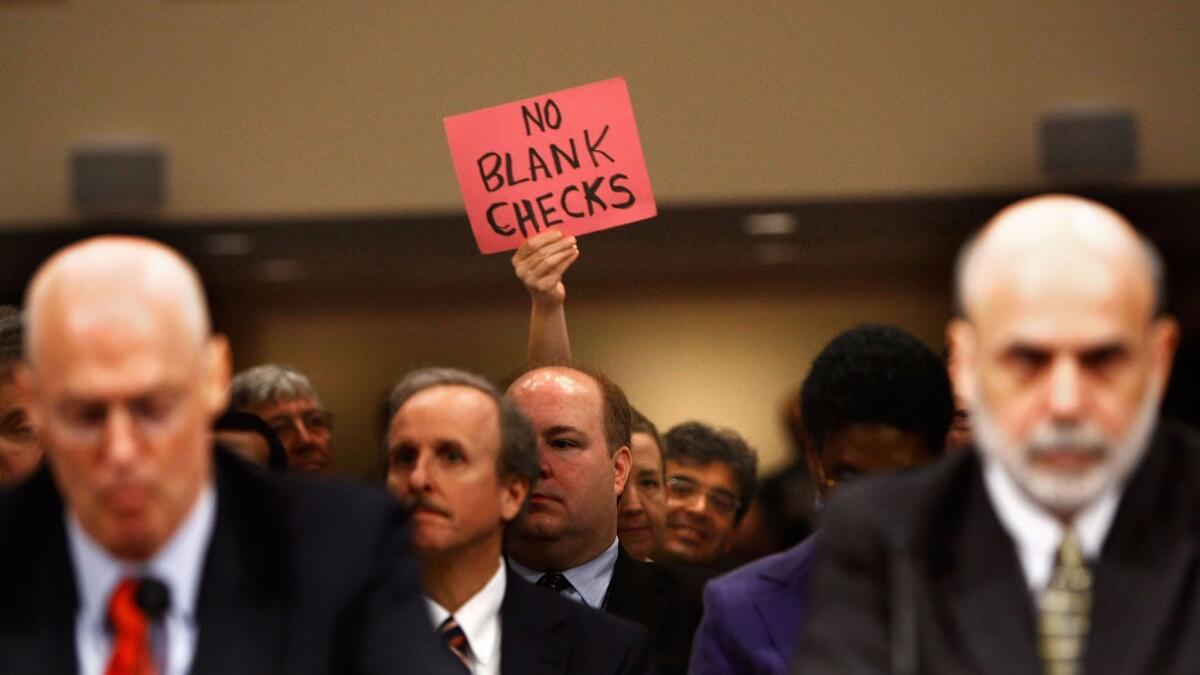

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, a consensus quickly developed in Washington: no more bank bailouts.

Nobody — lawmakers, government officials, regulators and certainly not average Americans — was happy about the hundreds of billions of dollars of taxpayer money pumped into banks and other firms to prevent a financial meltdown.

Although the money eventually was repaid, with the federal government even earning a small profit, Democrats and Republicans united in the desire to prevent a repeat.

But nearly nine years since the crisis, there’s no agreement on how to accomplish that goal.

The vastly different approaches of the two parties are at the center of the debate about financial regulation as the Trump administration and congressional Republicans target the slew of new rules put in place by Democrats with the 2010

Each side says its plan is the best way to avoid future bailouts and that the other’s actually increases the risks of them.

Dodd-Frank gives regulators new power called orderly liquidation authority to step in to safely and quickly wind down a major financial firm if it is too complex for a bankruptcy proceeding in the midst of a crisis.

The law allows for federal money to be used to keep commercial banks and other subsidiaries of the firm running during the shutdown. Any money not recovered by the sale of the firm’s assets is supposed to be recovered by an assessment on the financial industry, so Democrats said this plan prevents future bailouts.

But Republicans said the use of federal money to wind down a firm is a bailout and they doubt the funds ever would be recovered from the industry.

In April, President Trump ordered Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin to conduct a six-month review of the orderly liquidation authority, believed to be the first step toward recommending that Congress get rid of it.

The Financial Choice Act, passed by the House on a party line vote in June, does just that. It repeals the authority while changing bankruptcy law to better handle a large financial firm.

Here’s a look at the issue.

Dodd-Frank’s anti-bailout strategy

The 2008 financial crisis was triggered by the failure of Lehman Bros.

A scramble by federal officials to engineer a sale of the teetering investment banking giant fell apart in early September after the Treasury and the Federal Reserve decided not to provide government money to help secure a deal, as was done six months earlier for another failing investment bank, Bear Stearns.

On Sept. 15, 2008, Lehman filed for the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history. Investors panicked. The Dow Jones industrial average plummeted 504 points and another financial giant, insurer

Fearing a total meltdown of the financial system, federal officials stepped in to seize AIG in the coming days and pushed Congress to approve the $700-billion Troubled Asset Relief Program to help prop up the banking industry.

The AIG seizure was a complicated effort involving a pledge of $182 billion from the Fed and Treasury in exchange for a 92% ownership stake. The rescue allowed shareholders to avoid being wiped out, although they complained the government didn’t compensate them enough for the stake it acquired.

It took more than a year, starting in 2011, for federal officials to extricate the government from AIG. Treasury said the rescue netted taxpayers $22.7 billion in profit, but regulators and lawmakers agreed after the crisis they didn’t want to be put in that position again.

Democrats and key regulators believed the solution was orderly liquidation authority, which would mandate a shutdown of a company — not a rescue — but in a way that is designed to limit damage to the broader financial system.

How to shut down a failing financial giant

House Financial Choice Act

- Replaces orderly liquidation authority with new section of bankruptcy code designed for large complex financial institutions with more than $50 billion in assets

- Supreme Court chief justice designates special judges with experience to handle complex financial bankruptcies

- Cases get expedited treatment

- Assets are transferred into new company to keep subsidiaries operating

- Federal programs that could be used to provide emergency funding to a failing firm are repealed or restricted

Bankruptcy is the first choice for a failing financial giant. Dodd-Frank required such firms to submit plans called “living wills” to regulators in advance, detailing how they would be wound down if they neared collapse.

But if regulators determine the firm could not be shut down in Bankruptcy Court without threatening the broader U.S. financial system, they could use the authority to put it in federal receivership.

The FDIC then would wind down the company in the same way it now does with failing banks.

The law requires that the FDIC fire the firm’s management and that losses be taken by creditors and shareholders. The firm must be liquidated and Dodd-Frank specifically prohibits taxpayer money from being used to prevent the liquidation.

Dodd-Frank allows the FDIC to borrow money from the Treasury to wind down the company. But if the sale of the company’s assets doesn’t cover the cost of that, the money must be recovered through an assessment on the financial industry.

That mechanism would be similar to the assessment that banks now pay to the FDIC to cover deposit insurance.

“The mechanism is harsher than bankruptcy. The board is out. Top management is out. In bankruptcy, frequently they keep the board’s management in place,” said

“This is not a bailout mechanism,” she said. “This is a taxpayer-protection mechanism.”

Without orderly liquidation authority, Bair and other supporters argue, the prospect of another complex and lengthy bankruptcy like that of Lehman Bros. could lead to a bailout to protect the financial system.

Republicans prefer bankruptcy

“Contrary to Dodd-Frank … we will end bank bailouts once and for all,” Rep. Jeb Hensarling (R-Texas) told House members in June in pushing for the Financial Choice Act.

“We will replace bailout with bankruptcy,” said Hensarling, who authored the legislation and opposed the TARP legislation.

After the bailouts of the 2008 financial crisis, Republicans said they don’t trust regulators to stick to the liquidation authority rules, which would ultimately cost taxpayers money.

In a crisis that would warrant using the orderly liquidation authority, regulators would not want to further stress the financial system by assessing companies to pay for it, said J.W. Verret, an assistant professor at

“I think everybody understands that’s going to be unlikely in a crisis,” he said. “There’s no way in 2008 the government would have done a $200-billion to $300-billion assessment on the industry because it would have brought down a number of other institutions.”

In 2010, House Democrats wanted to set up a $150-billion fund as part of Dodd-Frank to pay for orderly liquidation authority ahead of time. But Republicans labeled it a bailout fund and Senate Democrats removed it.

Bair said having a fund in place instead of counting on an after-the-fact assessment would help ease concerns that the liquidation authority would cost taxpayers money.

“We fought hard for it,” said Bair, who headed the FDIC from 2006 to 2011. “Being able to pre-fund it would give people a lot of comfort.”

The Financial Choice Act would create a new section of the federal bankruptcy law to deal with financial institutions with more than $50 billion in assets. Special judges with the experience to handle such bankruptcies would handle the cases under expedited procedure.

“Judges sitting in open court instead of un-elected bureaucrats sitting behind closed doors will make consistent, predictable decisions based on decades of case law,” said Rep. David Trott (R-Mich.).

“More importantly, bankruptcy puts the risk of failure on the bank's shareholders and creditors, not the taxpayers,” he said.

But after the TARP rescues, which left bank shareholders largely intact, the liquidation authority was designed to prevent that. Dodd-Frank specifically says “creditors and shareholders will bear the losses.”

A possible compromise?

The debate over ending bailouts largely comes down to whether you believe regulators would recover the money from an orderly liquidation from the financial industry, Verret said. If not, “it’s bailout.”

Frederick Cannon, director of research at brokerage and investment bank Keefe, Bruyette & Woods, said that given how TARP turned a profit, he has a difficult time with the concerns about taxpayers recovering money used for a liquidation.

Beyond that, he said, neither the Democratic nor the Republican strategy for dealing with a failing financial giant is foolproof.

“Both of them have a good chance of not succeeding, especially in a systemic crisis,” Cannon said. But the liquidation authority “has a better chance of succeeding” than bankruptcy.

“If you’re a depositor at a bank, whether a big company or an individual, and suddenly the bank where your money is sitting is in bankruptcy in a new bankruptcy code and the judge says, ‘Don’t worry, your deposits are good,’ are you going to feel better about that?” he said. “Or will you feel better about the FDIC taking over the bank and saying, ‘We’re the guarantor of your deposits.’ ”

The best chance of success, he said, is to do both — enhance the bankruptcy code so it’s more able to handle a large financial firm’s collapse and leave the liquidation authority as a fail-safe.

“It may sound like belt and suspenders, but if the bankruptcy approach does not stabilize the institution you sure as heck better have a backup,” Cannon said.

Twitter: @JimPuzzanghera

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.