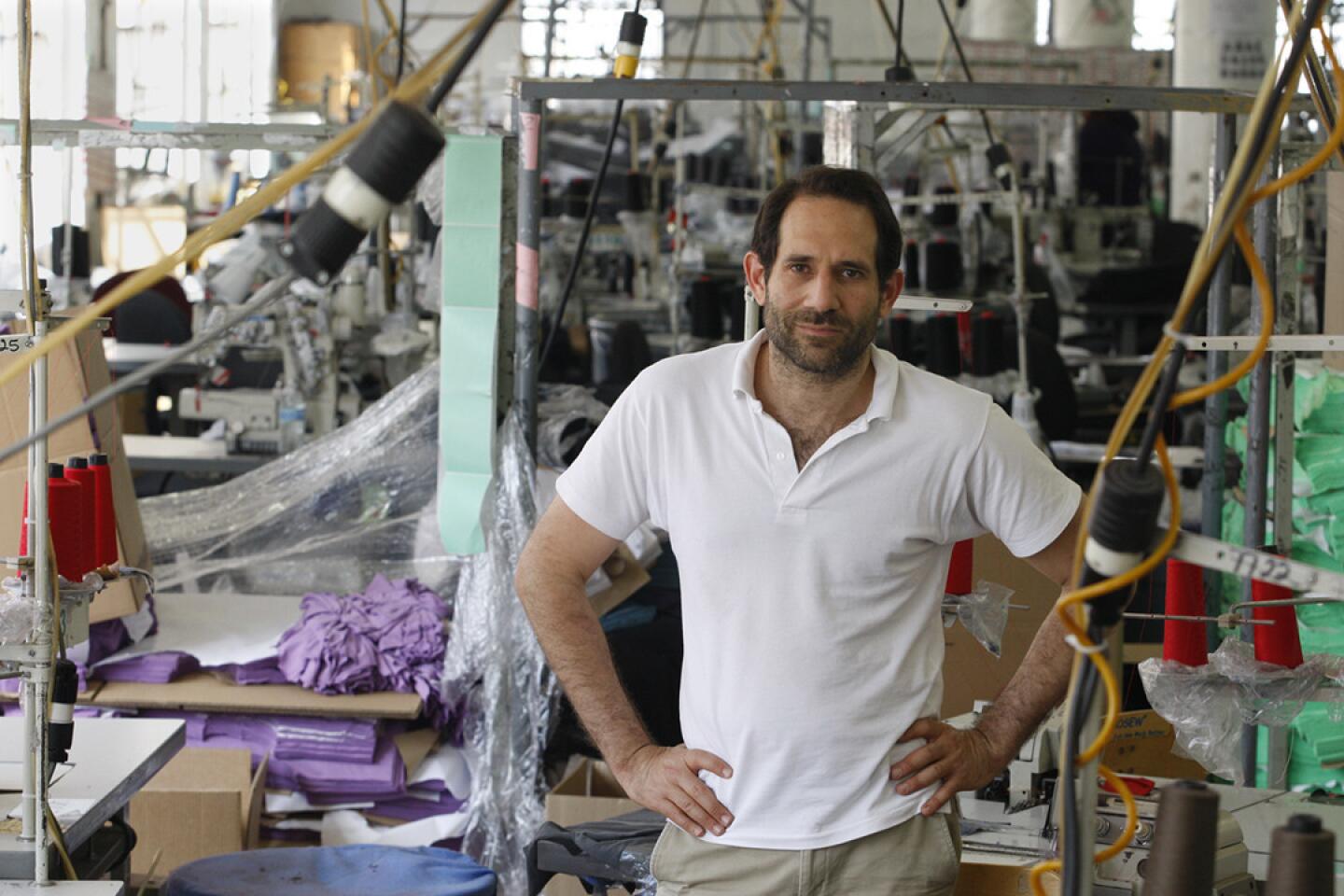

Q&A: Can American Apparel really stay in L.A.?

- Share via

With every turn in the saga that is American Apparel, experts wonder when the Los Angeles company will give up manufacturing in the U.S. and move offshore.

Even after filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on Monday, Chief Executive Paula Schneider said offshoring is not an option. The restructuring that lies ahead, she said, will enable American Apparel to keep production in the U.S.

“You can’t have American Apparel without apparel made in America,” she said. “It’s what sets us apart and what makes us different. That’s what makes us a really important company and a company that needs to thrive and be saved.”

SIGN UP for the free California Inc. business newsletter >>

Company executives have consistently pointed out the benefits of manufacturing in Los Angeles. Not only does American Apparel prominently tout its wages for employees on billboards, but it can respond to trends in the market and rush new products to stores quickly. American Apparel employs about 4,600 sewing and manufacturing workers in Southern California.

At this point, some analysts think that American Apparel is simply too married to the concept to ever change.

"Their brand is too heavily predicated on the U.S. manufacturing," said Josh Arnold, an equities analyst and contributor to financial site Seeking Alpha. "They have backed themselves into a corner. I don't think there is any circumstance that would make that change happen."

However, that doesn't stop retail experts from pointing out the upside to offshoring -- or even moving production elsewhere in the U.S.

Here are four arguments that analysts make for moving American Apparel's factories:

It's far cheaper to manufacture overseas.

American Apparel workers used to earn an average of about $12 an hour, but many have said that slowing production has pushed down their pay to about California's minimum wage of $9 an hour.

However, that pay still vastly outstrips the minimum wages of workers in countries with a heavy garment manufacturing industry. Indonesia, Vietnam and Bangladesh all have monthly minimum wages that can go as low as about $70, according to the International Labor Organization.

Retailers that are manufacturing in the U.S., especially for trendy fashions, often have a hard time competing against those who produce overseas, analysts said.

It's only going to get more expensive to stay in L.A.

Conditions will only get harder for American Apparel once the city's minimum wage is hiked up to $15 an hour by 2020. The company could save some costs by mechanizing more of production, some analysts suggest.

American Apparel has also faced immigration problems before. In 2009, American Apparel was forced to fire 1,800 skilled workers after an immigration inspection uncovered questionable employment documents. Some analysts say the company's financial troubles started at that point.

"After that immigration audit American Apparel had to scramble to replace inexpensive, experienced employees with expensive, inexperienced employees," said Matt Covington, a managing director with Conway MacKenzie, a financial consulting firm. "It really seemed like the Made in America economic model didn't work after they lost such a high percentage of workers."

It's cheaper elsewhere in the U.S.

Some American clothing companies have started moving parts of their production back to the U.S. from overseas -- a process known as reshoring. Rising wages in countries including Mexico and China, as well as higher transportation costs, are spurring the trend.

Some are coming to states with a rich history of textile manufacturing and lower minimum wages. In South Carolina, for example, the minimum wage is $7.25 an hour.

"Maybe there's a way to manufacture in a different part of the U.S.," Covington said. "Shift its labor jobs to a less expensive locale."

Young shoppers don't care where their clothes are made.

Teenagers and twentysomethings -- American Apparel's core demographic -- simply don't differentiate between products made in the U.S. and made elsewhere, analysts said. More important to them is the price and quality of the garment.

"Millennials are having a hard time getting a job," said Lloyd Greif, chief executive of Los Angeles investment banking firm Greif & Co. "The last thing they are worried about is, 'Hey, I want to pay $10 or $20 more for a garment that's made in America.'"

Young shoppers are interested, however, in buying apparel that is made in factories with good working conditions, Greif said. The brand won't be hurt, he said, as long as garments are produced in facilities overseas that don't use child labor and other abusive practices.

"The brand has a certain resonance, but that resonance has to do with a certain look and the marketing position," Greif said. "Not the fact it's made by unskilled workers in Los Angeles."

Follow Shan Li on Twitter @ByShanLi

ALSO:

Variable pricing may be a new theme at Disneyland

Lionsgate and Starz in advanced merger talks, sources say

In regaining CEO job, Twitter's Jack Dorsey follows in Steve Jobs' footsteps

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.