Column: Copyright boon or bane? Google Books survives another legal challenge

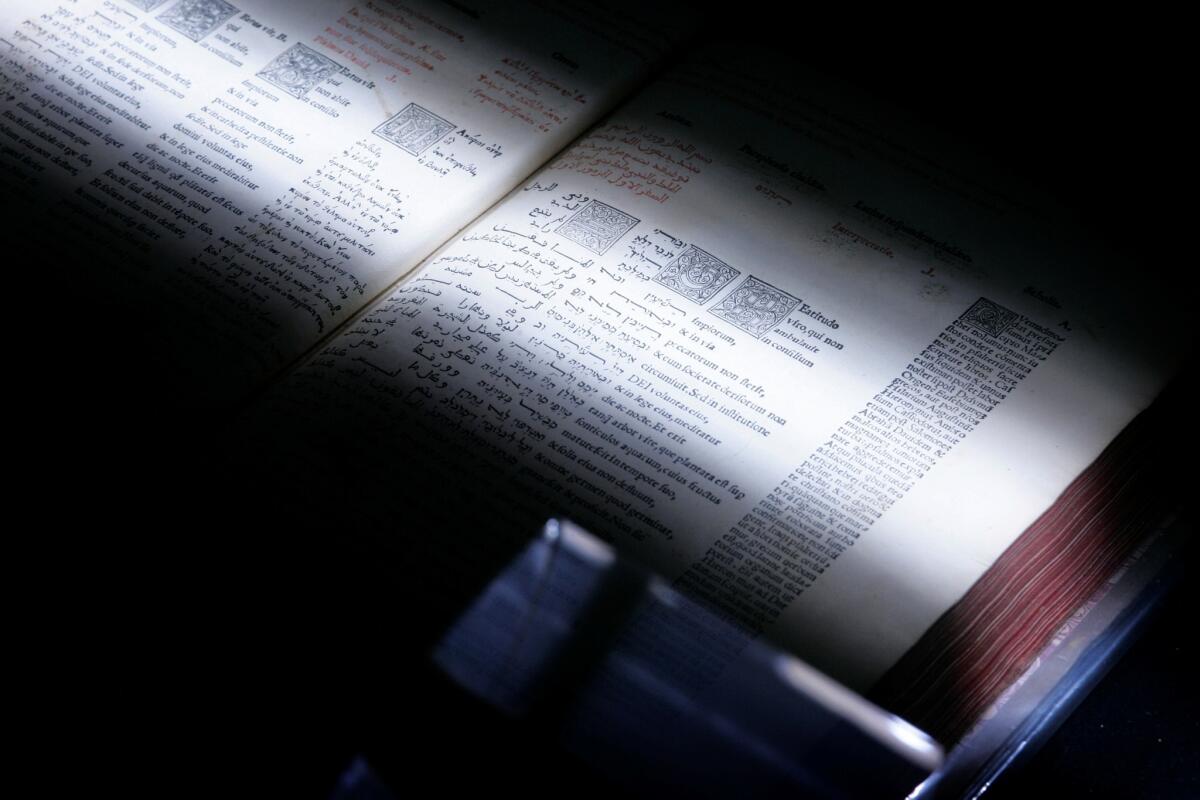

A scanner passes over an archival book at the University of Michigan on March 21, 2008, part of the creation of Google’s book search database.

- Share via

The long-running saga of Google Books and Google Book Search may have reached another milestone, thanks to a ruling in the big company’s favor from a New York federal appeals court. Researchers in all fields should feel relief. So should authors and publishers, who for a time were thought to be the inevitable victims of Google’s effort to digitize the world’s libraries. But the saga may not be over yet.

The 3-0 ruling handed down Friday by the U.S. 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals was written by Judge Pierre N. Laval, perhaps the leading expert in copyright law on the federal bench. Laval found that Google Book Search, which allows searchers to find “snippets” of books encompassing their search terms, is legal.

In effect, Laval codified what has become common practice on the Internet -- searching for words and phrases and seeing where they come up.

He concluded that Google Book Search fell well within the “fair use” provision of copyright law, which allows portions of copyrighted works to be used without their rights owners’ permission.

“This closes out this chapter in the evolution of copyright law,” James Grimmelmann, a copyright expert at the University of Maryland law school, told me. “The basic idea of making a search engine is pretty much settled.”

Fair use is what makes parodies, limited quotations, reviews and commentary legal when they’re based on copyrighted works. It’s a murky corner of copyright law, because the law doesn’t specify the boundaries of fair use. But a series of court rulings has helped define the concept. Among the tests is whether the use is for commercial purposes, how much of the original work is used, whether the use will cut into the market for the original work and whether it’s “transformative” -- a concept that Laval himself originated. In his ruling, he found that Google Book Search passed.

The ruling may be one of the last steps in the legal battle over Google Books. The project was announced in 2004 as the “Library Project”: Google had reached an agreement with 11 international libraries, including those of the University of California and Stanford, to scan books from their collections digitally to produce a machine-readable index of each one. Under the deals, the contributing libraries would get free digital copies of their own contributions, though they’d have to pay for access to the others’, as would anyone else.

Since then, Google has scanned and indexed about 20 million books, including copyrighted works and those in the public domain, mostly out-of-print nonfiction books. Google’s goal, as it was later described by co-founder Sergey Brin, was to create a global digitized library to “unlock the wisdom” imprisoned in the world’s out-of-print books.

Publishers and authors sued, arguing that the search function violated copyright law. Over the intervening eight years, the issues broadened, then narrowed again. For a time, the sticking points included the possibility that the company would acquire effective control over millions of works whose copyrights belong to others. These were “orphan works” -- copyrighted but out of print, whose rights holders can’t be found or identified.

Eventually, Google and the publishers reached an agreement involving a registry and fund for the missing rights holders if they turned up. But it was rejected by U.S. Circuit Judge Denny Chin of New York, who ruled that the copyright issues glossed over by the settlement needed to be resolved by Congress, not the courts. A publishers group later reached a settlement with Google outside Chin’s reach. The fate of orphan books is still up in the air.

Still unresolved was the question of the search function alone, which Google offers for free and without ads. Chin found that it was legal under copyright law, and the appeals court now has agreed.

Laval observed that Google had taken numerous steps to ensure that users could search, and only search, its digitized library. Each page of a book was divided into eight “snippets” of about three lines each; a search for a term would yield no more than one of those snippets per page. One snippet per page would be unsearchable, and one page of every 10 would be kept out of the database. This made it practically impossible for any user to, say, reconstruct a book or even a significant chunk of one through even a determined campaign of searching.

What was left, Laval concluded, was a transformative use of the copyrighted text, “which augments public knowledge by making available information about ... books without providing the public with a substantial substitute” for copyrighted material.

The snippets add to the transformative value of the basic search, he found, by contributing context: a user seeking books about Einstein’s theories who discovers “that a particular book includes 39 usages of ‘Einstein,’” he wrote, will conclude he or she can skip that book if the snippets reveal that Einstein “is the name of the author’s cat.” He implicitly agreed with Chin that, on balance, Google Book Search had the potential to increase, not diminish, book sales.

Anyone who spends time in digital archives (disclosure: guilty as charged) should be gratified by news that the amazingly useful Google Book Search has passed another legal test. But this ruling may not end the saga, and legitimate concerns about Google’s activities persist.

For one thing, the Author’s Guild has signaled its intention to appeal the ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court. For another, the issue of whether the world’s digital library should be left in the hands of a commercial institution hasn’t been resolved.

Even though Google donates copies of its scanned books to their source libraries, the fact remains that all the scans remain in the company’s hands. Whether it can resist the temptation to exploit them in some way contrary to the public interest is uncertain at best.

A group of scholars and institutions has founded the nonprofit Digital Public Library of America as a possible nonprofit counterweight to Google’s efforts, but it’s still in its early stages. It may be that the task of “unlocking the world’s wisdom” by converting its books to digital scans is one that only a company as determined as Google could achieve, but if so, that could be grounds for concern, not celebration.

Keep up to date with the Economy Hub. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see our Facebook page, or email [email protected]

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.