Great Read: A classic car mystery: Who owns the real ‘million-franc’ Delahaye?

In 1937, a Delahaye 145 backed by a American financer and driven by a French Jew set a new speed record and beat the dominant Germans at the Grand Prix. By the time Hitler invaded France two years later, and the car had been hidden in a remote

- Share via

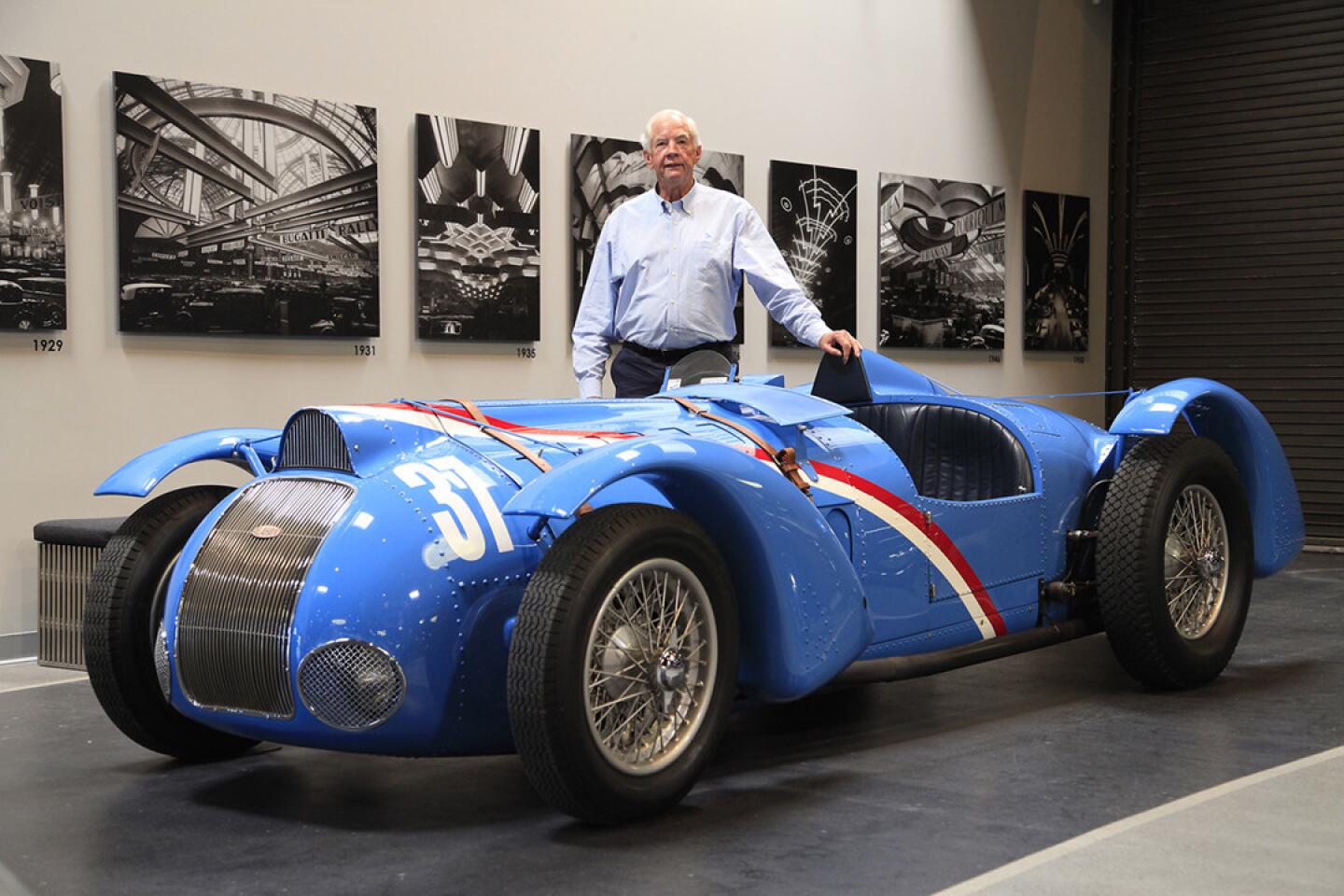

The bright blue vintage sports car sputtered to life and spewed smoke as it roared down a Monterey back street before stalling at a red light.

Tapping the temperature gauge nervously and struggling with the grinding gearbox, the driver shouted, “It actually runs pretty well — for an 80-year-old race car!”

The following day, parked among shinier and more coveted historic automobiles on the 18th green at Pebble Beach for the annual Concours d’Elegance, the Delahaye didn’t turn many heads.

But eight decades ago, it was a champion and arguably the most important car in the racing world.

On Aug. 27, 1937, French driver Rene Dreyfus broke a world speed record with the 12-cylinder Delahaye.

Seven months later, Dreyfus and his Delahaye beat a German car at a Grand Prix race in southern France.

SIGN UP for the free Great Reads newsletter >>

The victories won Dreyfus a share in a million-franc purse and brought pride to France, which had struggled to beat its Axis neighbors Germany and Italy on the racetrack.

The wins also placed car and driver in jeopardy.

The Delahaye was French, and Dreyfus was Jewish on his father’s side. German leader Adolf Hitler, furious that his Aryan athletes had been beaten at the 1936 Olympics by black American Jesse Owens, was further enraged that his government-sponsored automobile had been defeated by a French car and a Jewish driver.

Today, “the car that beat Hitler” is all but forgotten, except by racing historians, old car buffs — and two elderly millionaire car collectors. Each owns a version of the Delahaye coupe. Each has a historian backing him up. And each claims to own the one, true “Million Franc” race car.

::

In late 1936, fearful of war with Germany but determined to end its bellicose neighbor’s domination of auto racing, the French government and the Automobile Club of France offered a million-franc prize to any French driver, team or company that could set an automobile world speed record.

Executives and engineers at Bugatti, Talbot Lago, Renault and Delahaye set furiously to work. Delahaye soon emerged as the leader, having secured the backing of American heiress Lucy Schell and driving ace Dreyfus.

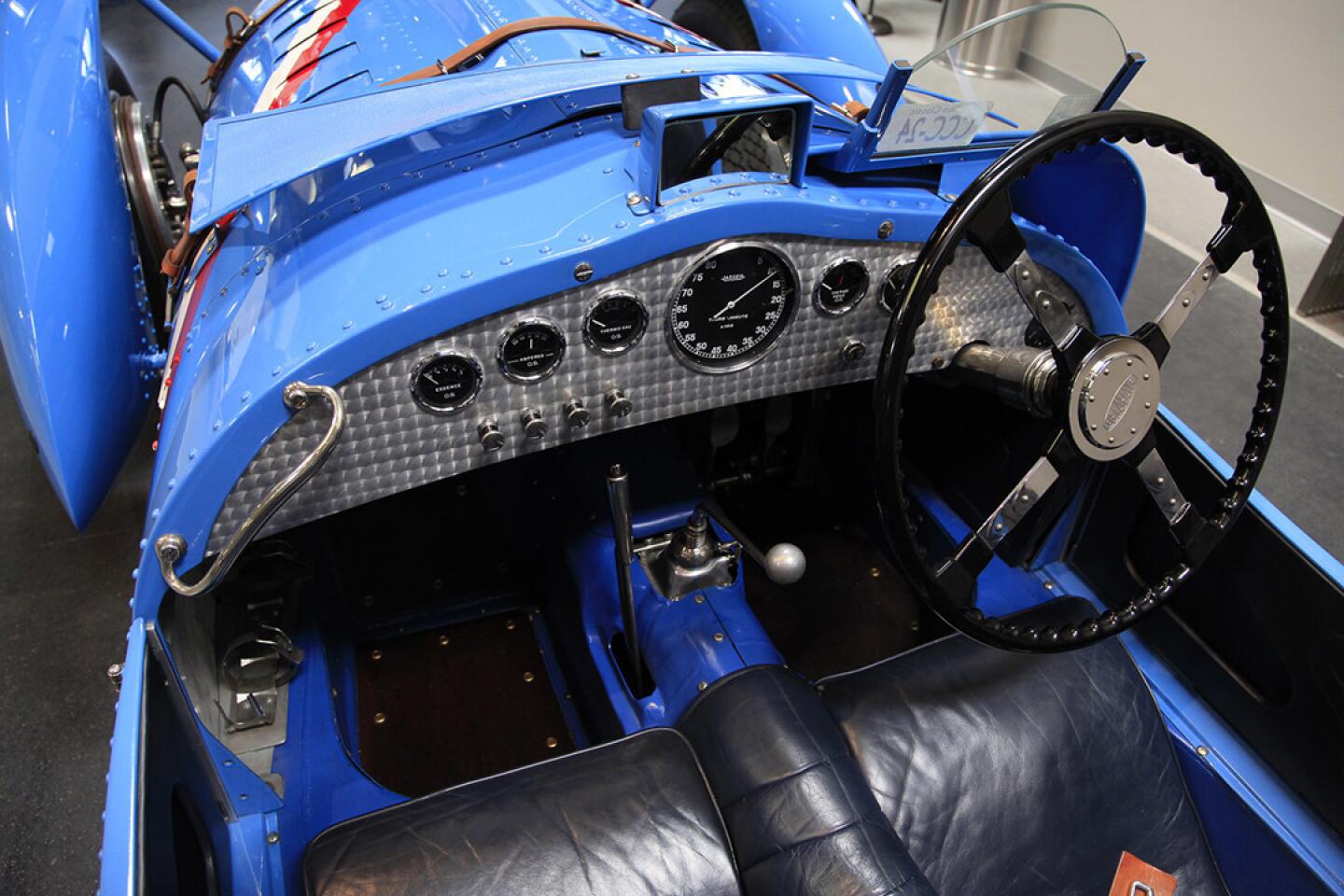

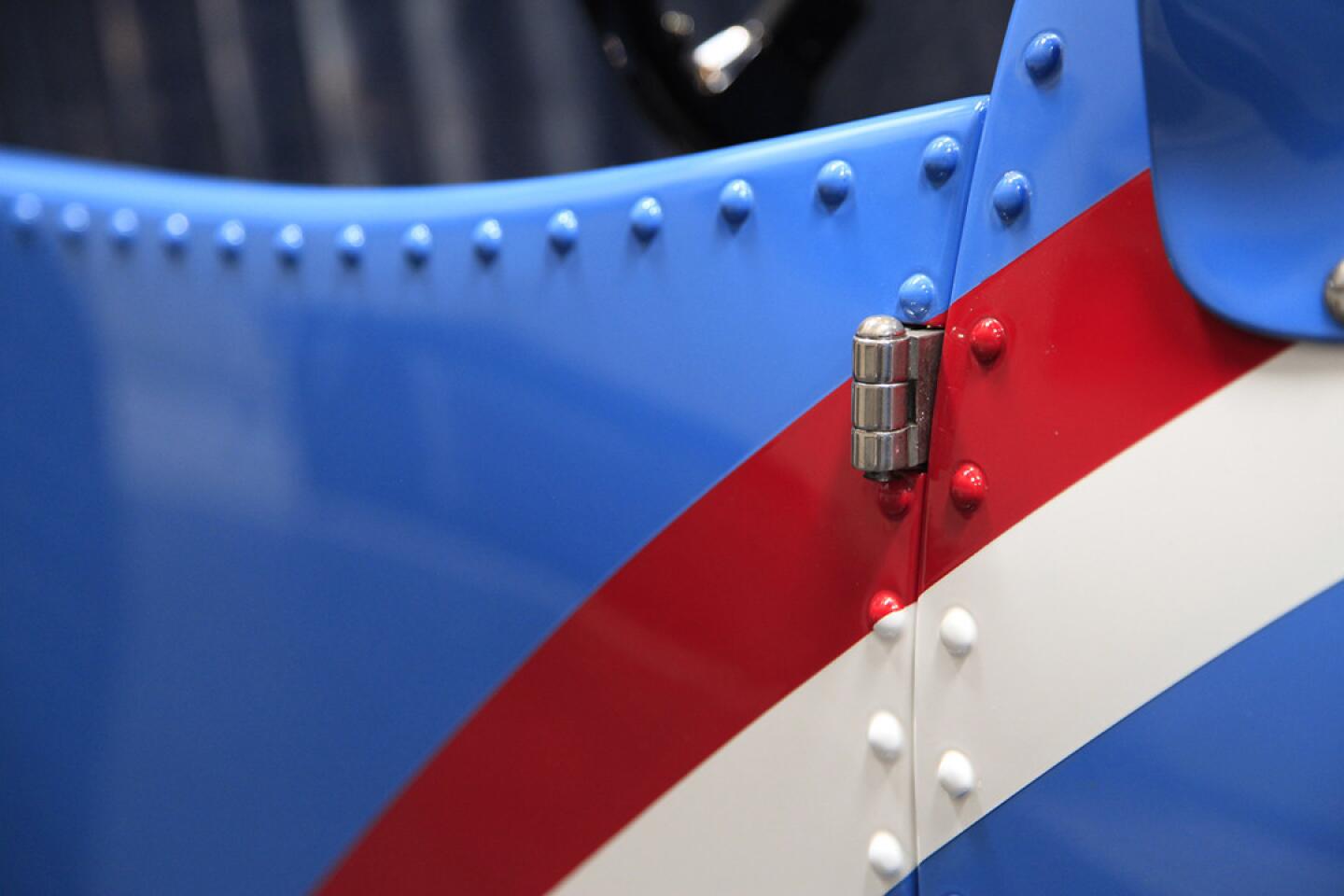

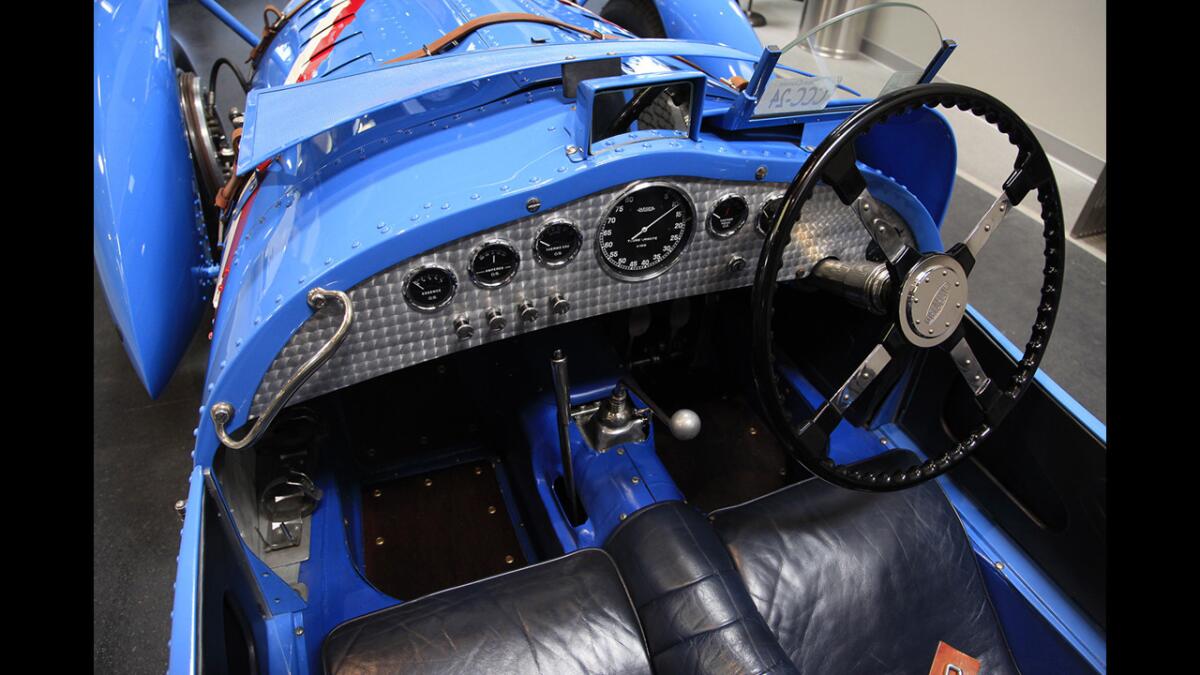

Schell and her Ecurie Bleue racing team funded the production of four aluminum-bodied Delahaye 145 racers. The slender, open-cockpit single-seaters were powered by huge 4.5-liter V-12 engines, capable of a top speed of 165 mph.

For months, Dreyfus and engineers ran test laps and made adjustments, cutting weight and increasing power wherever possible. The 145 lost its headlights and fenders. Then it was stripped of its lead-based blue paint, which removed six pounds. Trying different combinations, they ultimately settled, it is believed, on an unpainted body and a magnesium-block engine.

Given Hitler’s micromanaging, and his interest in automobiles, and his investment in Auto National and Mercedes, he was not happy about this. The German cars always won.

— Ken Gross, historian and car museum consultant

On Aug. 27, under the watchful eye of representatives from the Auto Club of France, Dreyfus drove 16 laps at the Montlhery racetrack outside Paris, covering 124 miles in one hour, 21 minutes and 491/2 seconds — a scant five seconds faster than the previous record.

The Ecurie Bleue team celebrated. So did France. Dreyfus’ victory got bigger headlines in the French newspapers than the day’s obituaries of banking titans Andrew Mellon and Baron de Rothschild.

Weeks later, the team headed to a European Grand Prix race in Pau, 500 miles south of Paris. Dreyfus regarded his chances as slim because he would face the German Mercedes-Benz Silver Arrow, which at 600 horsepower had twice the Delahaye’s thrust.

Dreyfus and his lighter, more nimble Delahaye were victorious.

“I don’t think I ever heard the Marseillaise played with such vigor,” Dreyfus wrote in his autobiography. “It had been so long no one could remember a French car and a French driver winning over a German car and a German driver. The crowd was incredibly emotional.”

The Fuhrer was infuriated, historians say.

“Given Hitler’s micromanaging, and his interest in automobiles, and his investment in Auto National and Mercedes, he was not happy about this,” said historian and car museum consultant Ken Gross. “The German cars always won.”

Dreyfus and the Delahaye pressed on. They followed the victory at Pau with another checkered flag at Ireland’s Cork Grand Prix in April 1938.

By then, Germany had already annexed Austria and set its sights on Czechoslovakia. In 1939, Hitler’s forces invaded Poland. France and Great Britain declared war. Within a year, Finland, Denmark, Norway and France were occupied by German forces.

Schell, fearing for her driver’s safety, sent Dreyfus to the U.S. to race in the Indianapolis 500. Hearing that the German forces had been ordered to find and destroy the Million Franc Delahaye, mechanics dismantled the racing team’s four vehicles.

“The engines were hidden away,” said Richard Adatto, an auto historian. “The chassis were stripped of their bodies.”

Many of the parts were stashed in a cave in northern France, where they remained until the end of the war.

::

In the 1960s, French car collector Serge Pozzoli acquired a Delahaye chassis. Then he found what is believed to be its original magnesium engine, on display at a trade school.

The interior of the 1937 Delahaye 145.

Over 20 years, Pozzoli tracked down other parts — a gear box, then a section of the body — while storing the car under the stands at Montlhery, the racetrack where the car first found fame.

In 1987, car collector Peter Mullin and his partner Jim Hull learned Pozzoli’s Delahaye was for sale. They paid $150,000, Hull remembers — “which was pretty good money, for a car that wasn’t running and wasn’t all there.”

Mullin, who has since become a classic car kingpin and is chairman of the Petersen Automotive Museum, was relatively new to car collecting but knew the automobile’s legacy, and he leaped at the chance to own it.

Hull said he oversaw the three-year restoration of the car’s body, chassis and, importantly, magnesium engine — the one stamped 48771, which matched the chassis stamp 48771. That corresponded with the number recorded by a French official (and confirmed in government documents in France by historian Adatto) on that 1937 race day at Montlhery.

Its blue paint restored, Mullin’s Million Franc Delahaye began winning prizes at car shows.

But soon it had company — and a contender for the Million Franc crown. While Mullin was restoring the Dreyfus car, and slowly accumulating random parts from Schell’s other Delahaye 145s, fellow car collector Sam Mann began showing another car.

This one, he said, was the real Million Franc Delahaye.

Years earlier, Mann had bought a 1937 Delahaye 145 Franay Cabriolet, a beautiful, streamlined convertible designed at the height of the French Art Deco automobile era. The car had started its life, he was told, as one of the Schell Delahayes.

He later acquired a second Delahaye, which was said to contain the remaining parts of Dreyfus’ record-setting race car.

Mann, 80, splits his time between homes in Malibu and New Jersey, where he keeps his massive car collection. He cites a different French car historian, Andre Vaucourt, who has studied chassis and motor numbers and concluded Mann’s Delahaye is the Delahaye.

Racing experts say the truth may be impossible to know. Although motors, chassis and bodies were usually stamped with serial numbers when they left the factories, race teams in the heat of competition constantly swapped parts indiscriminately, and they didn’t keep records. Chassis were sold and rebodied. Motors were rebuilt and renumbered.

Car expert Gross says it’s “probable” that Mullin’s is the one. So say two automotive restoration experts familiar with both cars, who would speak only on condition they not be identified because they have worked for both collectors.

Mullin, 75, says he had met Dreyfus and the driver confirmed that his was the winning Delahaye. The racing legend, who after the war became a U.S. citizen and gained celebrity as a New York restaurateur, died in 1993.

Seated inside his Delahaye in the Oxnard museum that bears his name, Mullin patted the bonnet and said, “I’m proud to own it.”

Mann feels just as certain that he owns the champion car. But in the gentlemanly way that characterizes the rarified vintage automobile world, he is willing to concede he might be wrong.

“I don’t know the answer, and I don’t know if there will ever be an answer,” he said. “Peter is a very good friend, and I don’t want to cast aspersions.”

At this year’s Monterey Car Week, both collectors brought their Delahayes to show. Mann’s Franay Cabriolet was named Most Elegant Convertible at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance.

Mullin drove his bright blue 145 in nearby Laguna Seca and won the Best in Class award for Pre- and Post-War Sports and Racing Cars at the competition known as the Quail.

The judges were not asked to decide which was the Million Franc car.

MORE GREAT READS

The most famous magician on Earth is a guy you’ve never heard of

Russia’s military clubs for teens: Proud patriotism or echoes of fascism?

Tethered by a string and trust, a blind sprinter and his guide make history

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.