Exploring the complex relationships with teen athletes and coaches with Piper Weiss and Ivy Pochoda

- Share via

There's a picture that has been on a bookshelf in my childhood bedroom since 1991. In it, I am 14. I've just won the U.S. National 14 and under squash championships. To one side is my opponent, who is holding her runner-up trophy like you might hold a dead fish — distant and disdainful. Next to her is the tournament director. On my other side is my coach — let's call him Mike, who had through some combination of tactics and affection guided me around my galloping nerves to victory.

A few months later, I found myself standing on the threshold of Mike's tiny studio apartment. Part of me wanted nothing more than to be invited in; the other refused to cross that doorstep. From where I stood, I could see the fold-out couch that doubled as a bed. The sheets were maroon and messy, very messy. Within a few months, Mike and I would start bickering, more like a couple than a student and a teacher. I was heartbroken. The next fall, he left my club for a different job, and I got a new coach, an older one. I stopped thinking about Mike, but never about his apartment and what I saw — the visceral, sexual side of my coach that needed to be kept secret from me for us to continue to work together in the pressured intimacy of the player-coach relationship.

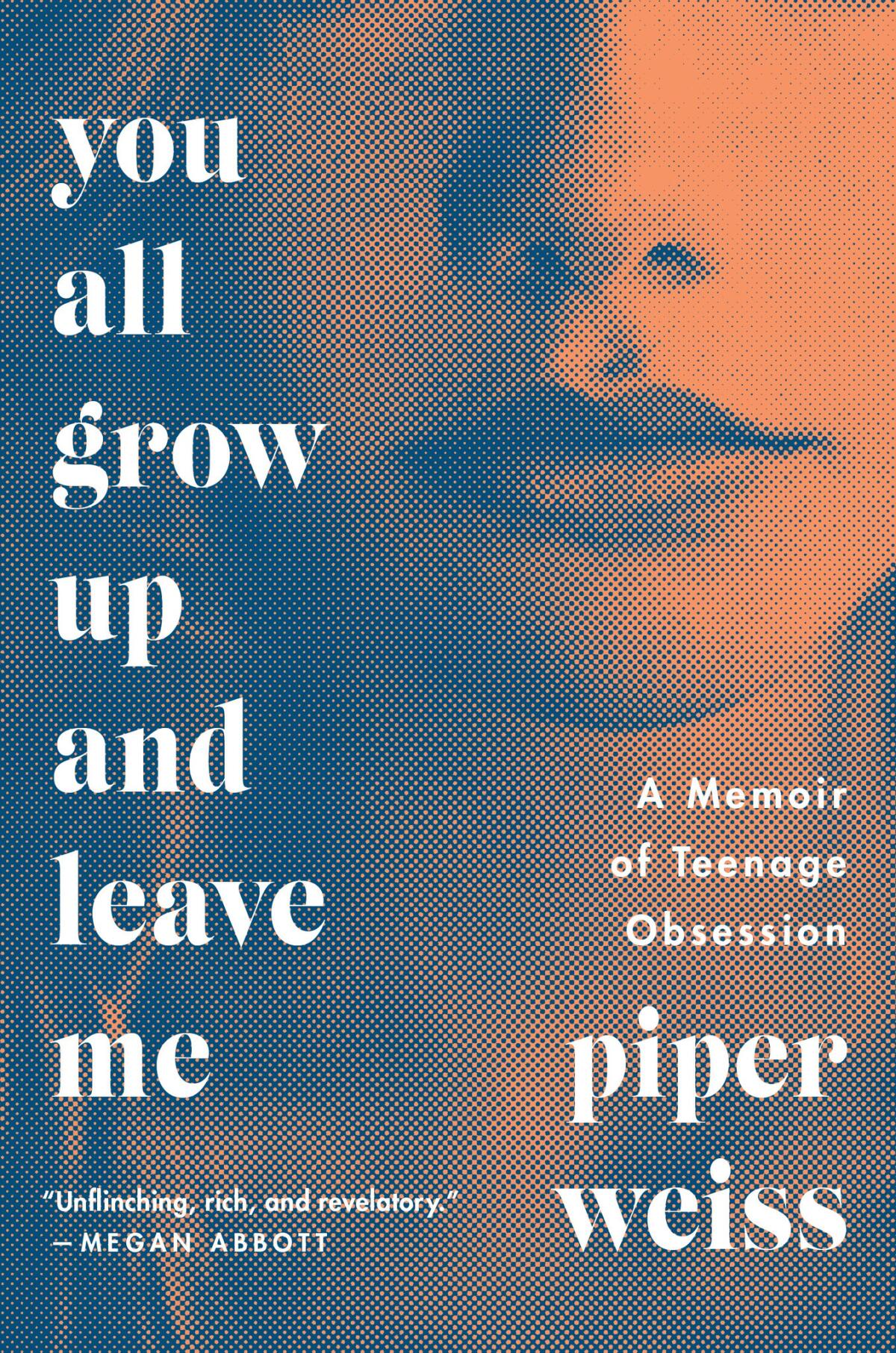

The strange and almost dangerous familiarity that develops between female players and their coaches is a Pandora's box that I must leave firmly shut if I want to continue to cherish the beauty and joy of my childhood (and later professional) sport. Lucky for me, in her brilliant debut memoir, "You All Grow Up and Leave Me" (William Morrow: 352 pp., $25.99), Piper Weiss was willing to take an ax to this box, splintering it into a thousand pieces and letting all the anxieties, discomforts, crises, frustrations and heartbreaks torpedo out.

I meet Piper in her garden apartment in Brooklyn Heights, which is a five-minute walk from Mike's former studio and smack dab in the middle of the neighborhood where my junior squash rivals lived — in other words, a perfect place for us to dive back into the sports that dominated our adolescence. Diminutive in stature and wearing somewhat dramatic daytime makeup and the sort of short floral dress I still associate with the cool kids circa 1992, Weiss doesn't immediately look like a product of the clubby, chauffeured elite Manhattan environment that she describes. She has written one of the most accurate and visceral portraits of the fraught emotional world of teenage sports (and teenage girls in general) — not to mention a pitch-perfect memoir of the narrow-slice life on New York's Upper East Side.

:: See Piper Weiss at The Last Bookstore Mon. May 21 at 7:30 p.m. with author Jennifer Romolini. ::

Piper and I have a lot in common — we are almost exactly the same age and we both grew up in the wonderfully uninhibited New York City of the early ’90s, where it was not unusual for 14- and 15-year-olds to find their way into bars and nightclubs. We both went to private schools, mine in Brooklyn and hers on Manhattan's uber-tony East End Avenue, and we both played racket sports. Whereas my story followed the more conventional pattern of a competitive junior athlete, Piper's took a darker and more devastating turn. When she was 13, her beloved coach, Gary Wilensky, a mash-up of Pee-wee Herman and Nick Bollettieri, killed himself after he botched the kidnapping of one of his star pupils. News of Wilensky's suicide was aired nationally on the show “Hard Copy” at the same time it was revealed that he had created a literal cabin of horrors equipped with handcuffs, S&M gear, chains, pulleys, sex dolls, nightgowns, sanitary napkins and wine coolers should his kidnap attempt have gone off without a hitch.

Out of this disaster, Weiss has crafted a book that marries true crime to memoir, plunging deep into the angry, messy heart of a teenage girl while exploring the horrifying — and eventually deadly — loneliness of an eternal outsider. In a more conventional book, Weiss would have stuck to the commonplace tenets of true crime reporting — the gruesome details, the investigation, interviews with fellow students and their parents. Instead, Weiss mines her memory of her early teens to excavate something darker and more personal: her feelings of disappointment that Wilensky didn't choose her as his intended victim and her questionable compulsion to defend him shortly after his death. It’s a startling take, and Weiss finds the answer for her action and reaction not in the sport of tennis or the confusing charisma of Wilensky, who often wore tutus and roller-skated on court and sent his students mixtapes and handmade Valentines, but in the heartsick and sometimes obsessive nature of teenage girls and their dangerously complex friendships.

"There was this inherent competition between all of us," Weiss says, as her cat runs figure eights across her ankles. "And with competition, you never fully trust the other person. It wasn't just tennis, but something in general with my experience with girls at that time. We were always comparing ourselves to each other in order to understand who we were. So we were always competing with one another, because inherently, it made us feel better or worse.”

Authors from David Foster Wallace to Megan Abbott have shown that sports provides the perfect microcosm for exploring and exploding real world anxieties from the personal to the global. Weiss uses tennis is a springboard to plunge into the neuroses and conflicts of her early teenage years — feelings of inferiority both in terms of appearance and ability. But sports also allows her to examine something inherent to teenage girls in particular, at least in my fairly clear memory of being that age — an overwhelming need to be liked, to be anointed, to be chosen.

"In sports," Weiss says, "you see your competitors as numbers. She's two. I'm three and so on. You are constantly measuring yourself. She has a good forehand. My backhand is weaker. But also, she's prettier, her breasts are smaller. I have this. You have that. The problem is you haven't defined who you are yet, and you can't look at another person as just a person. You're just like, ‘What does it mean to be me and who I am?’"

Coming into herself, figuring out who she was amid the misleading perfection of her classmates is the struggle at the center of Weiss' book. How does a short Jewish girl obsessed with Jim Morrison find her place in a world where blond, Hermès-swaddled superiority is the norm? In her estimation, Weiss was a perennial also-ran — not a loser, but not a card-carrying member of the in crowd — which conjured an endless longing for the right kind of friendships, attention from the right kind of boys, the right kind of body and for knowing the right way to behave.

This adolescent insecurity, this need to compare and to shine, is the precise tempest in which a manipulative coach like Wilensky thrived, giving his pupils what their friends (and even families) would not. Wilensky understood that more than instruction or improvement, his students — or “Gary's Girls,” as they were called — wanted a single thing — to be liked.

"I would be interested to see if boys back then had the same feeling as girls did," Weiss says. "We were taught that were weren't as strong as boys, and if we wanted to win at something, we had to use different tactics. And one of them was always the importance of being liked for whatever reason. At 13 or 14, you're not thinking that this should be physically or sexually, you’re just thinking that ‘I want to be liked, and then I'll have a foot in the door.’"

Wilensky liked his girls — his attempt to kidnap one led to his downfall. In some sports, certain activities open the door for an uncomfortable intimacy among adults and teens — long car rides, private dinners, late-night tutorials, events that set the stage for incremental transgressions but that could also be innocuous. In the insular bubble of Weiss' Upper East Side, where parents' blind faith in the safety of their inner circle, especially where a beloved and well-vetted coach was concerned, it was not unheard of for these types of transgressions to be overlooked, ignored, even encouraged — anything so that a superstar, or attractive college applicant, might emerge.

But here's the problem — the more of these moments that take place, the more difficult it becomes for a coach to conceal the very thing that needs to be concealed from his pupils, the reality of his adult life. Eventually, something will slip through the cracks, a post-coital bed, for instance, or a glimmer of a deep, dark disturbance. But even when Weiss glimpses a nefarious side to Wilensky, when he loses his temper with her training partner in inexplicable fashion, she still longs for a unique and personal connection to her coach. And it finally happens, right before the disastrous events that led to Wilensky's death, when alone in a car, in the evening after practice, he tells Weiss, "I'm depressed."

Instead of hearing alarm bells, Weiss, who had her own mental-health struggles at the time, finds something else — connection. She doesn't hear Wilensky's cry for help as much as she rejoices in finding a kindred spirit and relishes the fact that he considers her a worthy confidant. And this is where Weiss shines as a memoirist — seamlessly unveiling the unexpected and the startling, revealing the raw, ragged truth about her conflicted and slightly twisted teenage self.

Her joy is short-lived, of course. Because, although Wilensky confided in her, he did not ultimately choose Weiss. She was not his superstar, the object of his horrifying affection, a fact that burrowed so deep into Weiss she had to write a book about it to make peace with it and with herself as a teenager.

Pochoda is the author most recently of the novel “Wonder Valley.” She was a four-time all-American squash player.

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.