Why did Jonathan Lethem turn toward the desert in ‘The Feral Detective’?

- Share via

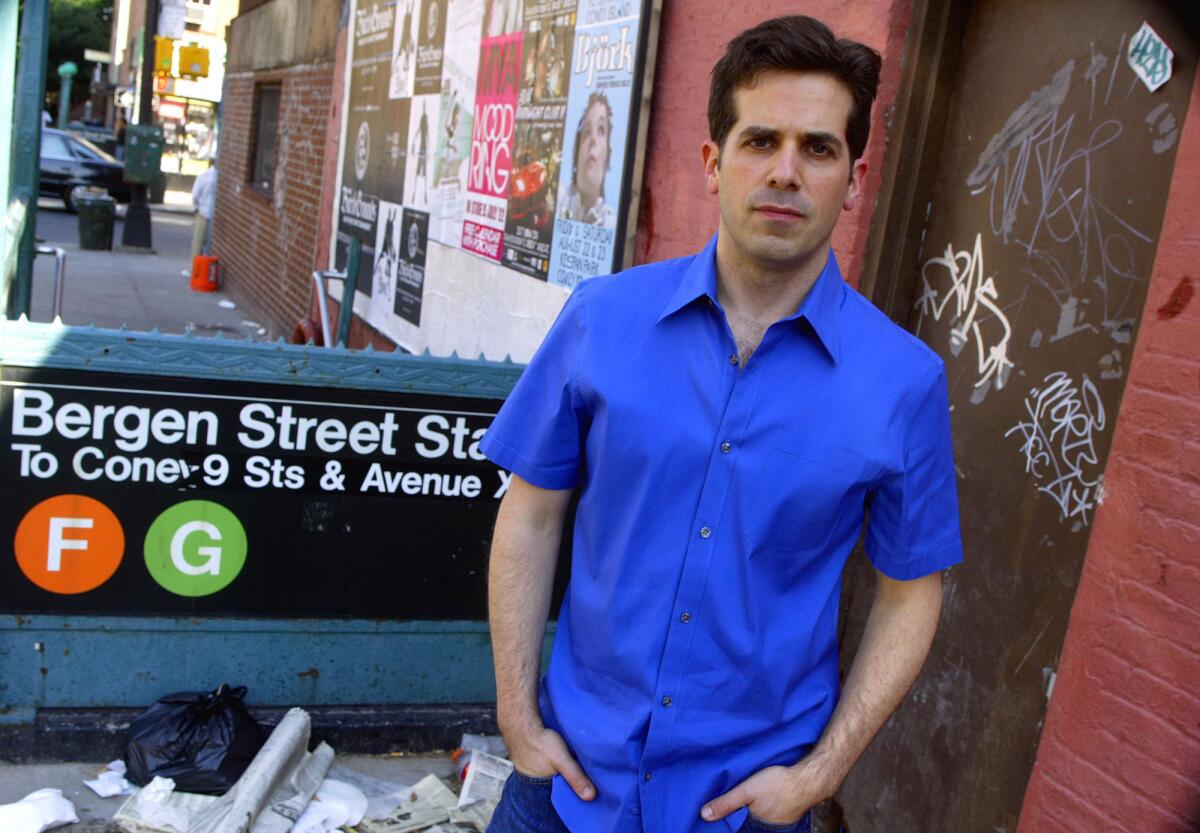

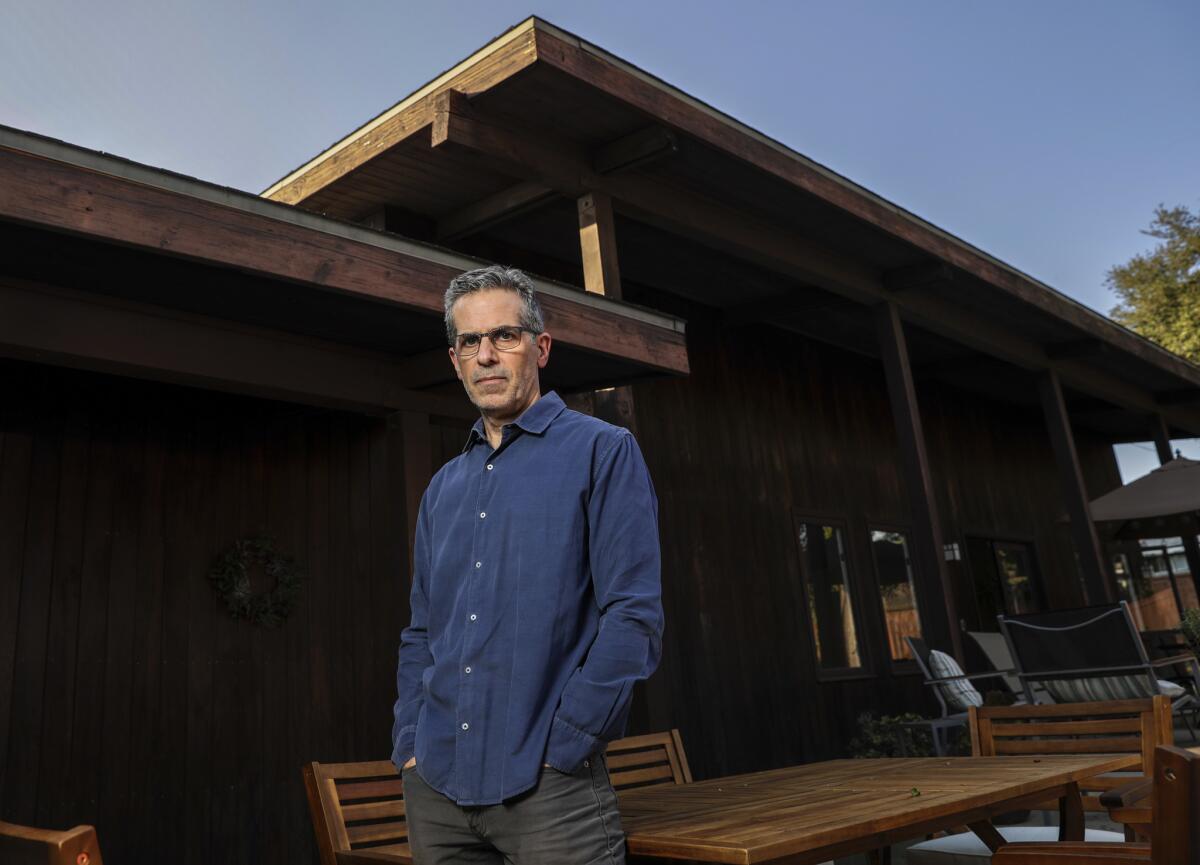

“I’ll drive,” Jonathan Lethem says, holding out his hand for my car keys. “This is going to be important, so you’ll want to take notes.” It’s a good thing he tells me that because nothing about the placid streets of Claremont, Calif., seems especially noteworthy.

As we drive away from Pomona College where Lethem has been teaching for the last nine years, we leave behind an enviable office with floor-to-ceiling bookshelves lined with his various passions — first editions of James, Melville and Calvino, classic sci-fi, scores of books on music and film (he’s written the introductions to several of them). There are even a handful of financial and accounting workbooks left by David Foster Wallace, whose chair in creative writing Lethem filled after Wallace’s suicide. The organization of the shelves reflects Lethem’s formative years in the used book business — half method, half madness.

Claremont looks more like the movie set of a college campus than a place of actual learning. “This is what they call ‘the land of trees and PhDs,’ ” Lethem says gesturing at the bucolic college 35 miles from downtown Los Angeles. “But now, this is where it gets interesting. This is the important part.”

We are approaching a nondescript north-south road with few stores and fewer houses. “This is Claremont Boulevard. It’s the border of Claremont and Upland. This is the county line.” In other words, we are about to leave Los Angeles County and enter San Bernardino County. This is not an insignificant border crossing; it is, in Lethem’s words, “a line of psychic demarcation.”

On the far side lies the world of his hypnotic new novel, “The Feral Detective,” out Nov. 6 from Ecco. At its core it is a novel of border crossings: from recognizable civilization to its opposite, from human to animal, from rationality to insanity, from the world as we knew it in the fall of 2016 to the world of what Lethem’s protagonist calls “the Beast-Elect,” and, yes, from Claremont to Upland.

I make no secret of the fact that I became the writer I am now after reading Lethem’s award-winning novel “Motherless Brooklyn” and his subsequent bestselling “The Fortress of Solitude,” both of which are set in my old neighborhood (our old neighborhood). For me Lethem is the quintessential Brooklyn writer — the person who captures the once exuberant grittiness of my Brooklyn. So I find it both funny and ironic that we are here in Southern California passing an enormous wash, an alluvial fan that catches the runoff from Mt. Baldy looming to the north, talking about our mutual fascination with the nearby Mojave Desert and our compulsion to write about it.

Lethem has been fixated on the West since childhood. “I grew up entrenched in mythic images of the West. I was into the hardboiled detective stories. I was into the Beat writers, and I was into western movies. I grew up reading a lot of things like ‘Dharma Bums’ and Nathanael West, Ross MacDonald and Chandler and their imitators.” In his 20s he moved to the Bay Area, where he “began to think about writing about California and the West in a less hysterical, romantic way, from a less mythic position.” In his latest book he has finally done just that.

“The Feral Detective,” which marks Lethem’s first return to the hardboiled genre since “Motherless Brooklyn,” arose from the mental and topographical realignment he experienced after moving to Claremont. “Initially,” he says, “I imagined I was moving to Los Angeles. I thought OK, what’s my psychic geography going to be? I’m going to be looking from Claremont westward. So how far am I from the beaches? How far am I from the Hollywood sign? I would spend a certain amount of energy going west both mentally and actually doing it, visiting people who lived in Venice or West Hollywood.”

But then came the geographical and psychological shift. As more and more friends pulled off the highway to visit him on their way out to Joshua Tree and the high desert, he realized, “Wait a minute, I don’t live in L.A., I live on the western edge of the Mojave.” So he reoriented — no longer looking west but facing east, confronting the strange, wild and somewhat unknowable world unfolding just over the county line.

Which is exactly where he and I are standing. We’ve just parked the car in a bleak strip mall, catty-corner to an even bleaker strip mall where Lethem’s feral detective, Charles Heist, has an office on the second floor. Although we are only five minutes from the PG-13 charm of Claremont, we are in a different world — one of sex shops, illegal pot dispensaries, more sex shops, rumored prostitution rings and dubious massage parlors. At Prep & Save, an all-purpose apocalypse survival shop that sells everything from body armor to 1-pound cans of freeze-dried turkey tetrazzini, the owner greets Lethem like a regular. (He only visits the store for research, he tells me.)

To understand “The Feral Detective” you have to savor the strangeness of Upland, both as a town and as a setting for fiction. Upland is a product of the old Los Angeles blue laws that pushed all questionable pursuits across the county line. It’s also, in Lethem’s estimation, the start of the desert. And while that might not be perfectly accurate in terms of topography, in every other way that matters he’s bang on. When Lethem is talking desert he’s not making much of a distinction between the natural landscape and the social one — or perhaps I should say the antisocial one, where conventions are tossed and rules abandoned.

We backtrack a bit from the strip mall to an area called the Wash, which Lethem has been talking about excitedly since we got into the car. “It’s right here,” he says, “it’s this giant expanse that you have to pass to get from Claremont to Upland, but people don’t even know it’s there. They overlook it. It’s easier to ignore it.”

The San Antonio Wash is about the size of 40 football fields situated in an unincorporated zone, a literal no man’s land between Claremont and Upland. It’s deep and steep in places, and it floods easily in a rainstorm (an event that figures prominently in “The Feral Detective”). It’s surrounded by a chicken-wire fence topped with barbed wire. But most interestingly the wash is where the desert leaks in — a canyon of scrub brush, hardscrabble plants and cracked earth smack in the middle of two well developed towns.

For those unaccustomed to it the desert it’s difficult to confront, to absorb and to digest. This is what Lethem calls the desert’s “incommensurability.” It dares you to look away or to flinch. The first time I visited the Mojave I became dizzy and disoriented by the scope and scale, unable to configure a place for myself within all that empty space. Lethem was also drawn by “what happens to the human psyche under all that pressure the desert exerts.”

This is why the hero of “The Feral Detective” is not the titular character but Phoebe Siegler, a 32-year-old New Yorker who, like Lethem, like myself, like most of you reading this, found herself unmoored in the aftermath of the 2016 election.

Phoebe travels to the desert searching for the missing daughter of her best friend who may or may not have embarked on a Leonard Cohen-inspired pilgrimage to Mt. Baldy. She becomes entangled both professionally and romantically with the hairy Heist (side note: Lethem can write the hell out of a sex scene), who leads her up the mountain, away from civilization and into an off-the-grid world untouched by and most likely unaware of the outcome of the election — a feral world.

“When I’d begun to believe that I was grounded enough here that I could begin to think like a writer about it,” Lethem says, “I was also traveling east into the desert a lot and investing myself in this sort of Inland Empire desert identity, and at the same time I was thinking a lot about ferality, which is something that has nagged at my work for a long time.”

If you’re having trouble getting this, take a closer look at the feral children in “The Fortress of Solitude” or the orphaned, Tourettic detective in “Motherless Brooklyn” and you’ll find that Lethem has been here before.

It’s this engagement with what he calls “the edge of human,” both in terms of landscape and behavior (and perhaps politics) that gives “The Feral Detective” its extraordinary texture. Lethem leads us to the limit of our conventions, then drags us past them into a world most people are comfortable overlooking, ignoring or denying. But even here, where nothing and no one behaves according to rational principles, Lethem manages to find “the weird underbelly of things to identify with.” Which means, at least to me, that his reorientation is complete, an East Coast transplant firmly entrenched in the strange mysteries of the Inland Empire, writing with his back to the Pacific, looking away from expected California into an environment that is infinitely more captivating.

Pochoda’s most recent book is 2017’s “Wonder Valley,” which won the Strand Magazine Critics Award for best novel.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.