Los Angeles is refracted in all its irreducible, unexplainable glory in ‘Dear Los Angeles’

- Share via

Even — and perhaps especially — for those of us who live in Los Angeles, it can be difficult to find a vantage point from which to view this strange and sundry city objectively, comprehensively. Fog and smog obscure, traffic congests, buildings dominate the skyline, mountains jut up out of nowhere, neighborhoods extend beyond the horizon — so much unseen, leaving our explanations of our city incomplete, incalculable, incompatible. We’re left to wonder what this place is exactly…

Is L.A., as Aldous Huxley wrote, “the place of virtualities, where absolutely anything might happen”? Or is it, as Willa Cather thought, “the most horrible, unreal place in the world”? Is it Harriet Harper’s “garden spot of America” or John Gielgud’s “horror of ugliness, flat as your hand and crawling with cars”?

“I try to rationalize this whole country, and excuse it,” Eric Knight wrote of Los Angeles in 1934, but what “Dear Los Angeles: The City in Diaries and Letters 1542 to 2018” shows us is that L.A. is a place that can’t be rationalized, explained or excused. “The impossible city,” claimed Italo Calvino, lovingly.

It’s too expansive, too extraordinary, too inconceivable, too multifarious — simultaneously Harper’s garden, Gielgud’s horror and infinite other brittle impressions that gain strength and precision only through their collective communion. The city is a blackbird that must be looked at in even more than Wallace Stevens’ 13 ways — or perhaps it’s a different beast entirely, “a mountain lion we only glimpse in shutter-quick flashes,” as David Kipen, the book’s editor, writes in his preface.

“Dear Los Angeles” follows in the footsteps of the Modern Library’s “New York Diaries” (2012), a similarly massive collage of literary morsels focused on New York City, L.A.’s snooty older sibling. Kipen’s new compendium collects fragmentary views of Los Angeles, from nearly 500 years of letters and diaries, turning the City of Angels into a city of angles, glimpses, shards of perception, like a million little slivers of a broken mirror, all reflecting different images of our disparate city back to us.

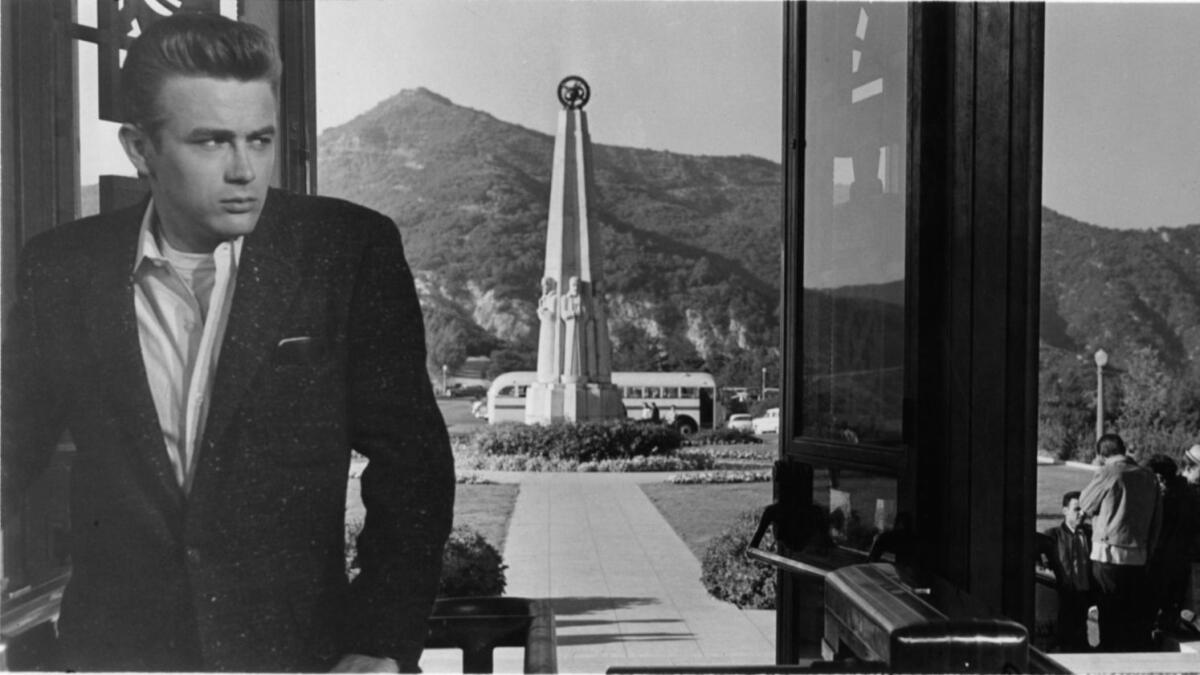

In its whorl of historical scraps, we witness Alistair Cooke describing Bobby Kennedy’s corpse on the floor of the Ambassador Hotel, Philip K. Dick calling Disneyland “the last sane place,” John Lennon apologizing to Pam Grier for getting her kicked out of a Smothers Brothers show, Groucho Marx thanking Peter Lorre for sending him Stuart Gilbert’s study of James Joyce’s “Ulysses,” Octavia E. Butler acknowledging her “fear of people and worms,” James Dean declaring “I WANT TO DIE,” Christopher Isherwood admitting his fancy for reading Lord Byron’s letters on the toilet (particularly during defecations) and Carey McWilliams jotting down an idea for a potential project: “Do a group of stories about Los Angelesians in the manner of Joyce’s ‘Dubliners.’”

There are repetitions and reverberations throughout. Some of the dramatis personae show up regularly, including Isherwood and Butler; also Anaïs Nin and Dalton Trumbo, Aoki Hisa and Tennessee Williams, Charles Brackett and M.F.K. Fisher. They wander in and out of the room like indifferent lovers.

Sometimes certain images and ideas one writer brings up will resurface in the words of another of the city’s denizens. In one passage, John Fowles writes, “The night view is very beautiful, a spill of jewels glittering in limpid air.” Pages later (though written years before), we see Eleanor Roosevelt echoing Fowles’ shimmering impression: “But the most impressive time to fly in to Los Angeles is at night, when all the lights are on and the city lies below you like a multi-colored heap of jewels.”

A number of the fragments in “Dear Los Angeles” are master classes in micro-storytelling. For example, this perfect John Cheever vignette: “I never found the tar-pits in Los Angeles, but I had a dish of Spam with raisin sauce at the Thrifty Drug Store.” Elsewhere, the following poetic premonition from Malcolm Lowry: “The tree outside is sad. It will die, I think.”

All these bits and pieces were plucked from their diarial and epistolary sources, according to Kipen, “because they told [him] something about [his] city.” Though many of the entries offer riveting views of and perspectives on Los Angeles, the juxtapositions sometimes feel less meaningful, determined mostly by the impediments of the book’s idiosyncratic formal conceit.

Borrowing its structure from its New York predecessor, the book is separated into calendar dates, starting with Jan. 1 and ending on the last day of December. Each date has excerpts across that 500-year span. For Jan. 1, we encounter an 1853 fragment from Judge Benjamin Hayes, jump to 1923 to meet Sister Aimee Semple McPherson, skip to 1934 for a few sentences from G. McGrama, then sample some lines from Isherwood in 1941 and end with a bit from Aaron Paley in 1985 — only to lurch back to 1848 in the first fragment of the next calendar day, Jan. 2.

Kipen, one of The Times’ critics at large, argues that the calendar arrangement offered him the best method to organize this cacophony of metropolitan madness: “One step forward, two centuries back — the perennial, quixotic spectacle of L.A. forever finding fresh mistakes to make.”

While I disagreed with him on this point at first blush, the calendar format won me over by around mid-May (not quite halfway through the book). A year is a cycle, one revolution, made up of 365 or 366 minor revolutions. Thus, the book is set up to highlight these concentric circles of culture, hundreds of years sharing a single circadian rhythm. They rotate together, through each date, and through the calendar year — decades, centuries, turning in unison day by day through the seasons. (As though Los Angeles has seasons.)

As I let the fragments wash over me like frothy waves at the Santa Monica shore, I began to realize that maybe, in its own way, this was McWilliams’ idea come to fruition: a “Dubliners” of Angelenos — or perhaps it’s Robert Altman’s film “Short Cuts,” a story cycle of Los Angeles residents, told in the form of one of those fragmentary novels from David Markson’s final quartet.

William Faulkner certainly couldn’t sound any more Marksonian than he does here: “I have considerable talent, perhaps as good as any coeval. But I am 46 now. So what I will mean soon by ‘have’ is ‘had.’”

In his preface, Kipen describes his book as “a collective self-portrait of Los Angeles when it thought nobody was looking.” There is much to be gleaned from scrutinizing the style of the portraiture. “Dear Los Angeles” is notably not a panorama, a cityscape in extreme long shot, the whole of the sprawling metropolis framed in wide angle; it’s a series of snapshots, fast cuts, shutter-quick flashes, slides swiftly clicking by in a projector.

Even if one snapshot doesn’t seem particularly enlightening, each gains iridescence by rubbing shoulders with the rest in the calendrical procession of partial portraits. To borrow some words from one of Eric Knight’s contributions to the book: “I know that out of all this hodge-podge there must come something.”

The something that emerges is intangible, irreducible, unexplainable, but it is there, like a ghost, a memory, lingering. The something that emerges is the impossible city itself — or at least its trace, which begins to grow clearer as we read “Dear Los Angeles.” Yet it always, inevitably remains just out of reach: the haze on the horizon — a city perpetually disappearing, disappeared.

Malone is a writer based in Southern California. He is the founder and editor in chief of the Scofield. His work has appeared in Lapham’s Quarterly, Literary Hub and the L.A. Review of Books.

“Dear Los Angeles: The City in Diaries and Letters, 1542 to 2018”

David Kipen, editor

Modern Library: 576 pp., $26

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.