Teju Cole uses his camera and his writing to pry open the cities he visits in ‘Blind Spot’

- Share via

In “A Treatise on Relics,” John Calvin, decrying the proliferation of fake Christian relics throughout the world, singles out the splinters of the True Cross, which, he claims, are so numerable throughout Europe that, “if we were to collect all these pieces of the True Cross exhibited in various parts, they would form a whole ship’s cargo.”

Calvin’s comment appears in Teju Cole’s latest book, “Blind Spot,” a hybrid work of photography and writing that spans the globe in a series of small, closely observed moments. The line comes in the middle of a short discursion on the nature of sleep, accompanied by a photo of a boy sleeping, Christ-like, on a wooden table, and Cole doesn’t spend much time elaborating on Calvin’s quip, but it speaks to a central preoccupation in the book: the nature of truth, and the power of the fragment.

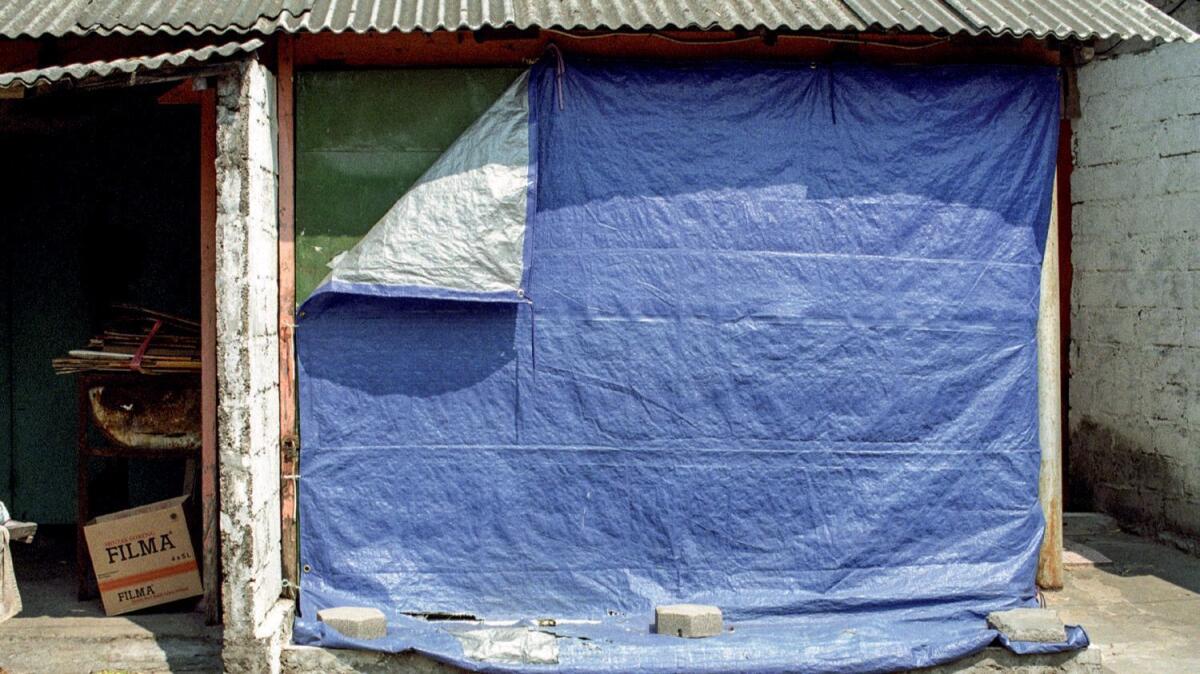

Like a splinter of the True Cross, the photograph above all testifies that photographer and camera were at a certain place and a certain time, bearing witness. The images in “Blind Spot,” paired together, form a travelogue of a global flâneur, as Cole strolls through Tivoli, Brooklyn and Brazzaville, his camera capturing glimpses and fleeting impressions. Each image in the book offers a single moment in time, a stand-alone enigma, accompanied by a brief block of text on the facing page, naming its location and offering further illumination. Often the book focuses on small, easily missed moments cropped out of the fabric of everyday life; as Cole writes in the postscript, in some cases, the images “showed me more about a place than I might have seen otherwise.”

A ladder in an Italian cemetery, for example, calls forth a line from Dante (“I saw a ladder, glimmering like gold/ Lit by a sunbeam”). An excavated pile of dirt alongside Palm Beach McMansions becomes a memento mori: “The pile of earth at the time seemed constructive, and only later did it appear deathly. But soil seemed by then the only real in this sordid excess of simulacra. Et in Arcadia ego.” References to a European religious and philosophical tradition abound, from Pliny the Elder to Giodarno Bruno, alongside nods to Emily Dickinson, Derek Walcott and even Beck and Sufjan Stevens. Often, the photograph and text complement each other, but just as often, contrasts emerge. A jaunty mural of a school of tuna in Treasure Beach, Jamaica, is accompanied by a description of J.M.W. Turner’s bleak and horrifying painting, “Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying.”

As its title suggests, “Blind Spot” focuses on the shortcomings of vision (including references to Cole’s own partial loss of sight in 2011). But it is also about the shortcomings of photography itself. “Photography is good at showing neither political detail nor political sweep,” Cole writes. “Politics is a matter of discourse and discursive compromise. Photography can show violence and its aftermath, it can show laughing faces, or romantic sentiment. Photography is quite good at metaphor and at evocation. But politics is elsewhere, hard to compress into a rectangular frame.” Accompanying this discussion is a close-up of a Lebanese cedar, a non sequitur that works to highlight the gaps and the absences that define documentation and nonfiction.

“Blind Spot” features the same quality of Cole’s luminous prose, but if his earlier works, including his PEN/Hemingway-winning debut novel “Open City,” favored longer sentences flavored with Proustian digression, the writing here is tighter, more condensed. Like the images, the writing here is often dramatically cropped, offering fragments in lieu of extended arguments and reveries.

But despite this stylistic difference, “Blind Spot” continues many of the same obsessions that drive Cole’s earlier work (his two novels, “Open City” and “Every Day Is for the Thief,” as well as his collection of essays, “Known and Strange Things”): the limits of sight, travel and nomadism, and the unexpected ways in which suppressed history and memory can return unbidden. Indeed, in the postscript he notes that while the book stands on its own, “it can also be seen as the fourth in a quartet of books about the limits of vision.” (Not just Cole’s own works: “Blind Spot” feels connected to other writing as well, including André Breton’s “Nadja” and the writings of W.G. Sebald, with whom he is often compared and whose name is subtly invoked with Nuremberg’s Saint Sebaldus Cathedral.)

In fact, “Open City” might have been a more appropriate title for this book than Cole’s earlier novel, since again and again Cole is using his camera and his writing to pry open the cities he visits. After a while, the place names heading each vignette start to seem misleading, as they are often the least relevant part of the image: While these geotags speak to a need to categorize experience by nationality and nationalism, the book’s main job is to thoroughly undermine such affiliations. On his website, Cole cites his debt to Italo Calvino’s book “Invisible Cities,” in particular the chapters on “Continuous Cities” and the idea, as Cole puts it, that “there is actually just one big, continuous city that does not begin or end: ‘Only the name of the airport changes.’” He continues: “What is then interesting is to find, in that continuity, the less-obvious differences of texture: the signs, the markings, the assemblages, the things hiding in plain sight in each cityscape or landscape.”

In place of national boundaries and cultural definitions, Cole builds up diptychs and triptychs: The Italian cemetery ladder image, for example, is followed by a description of descending a ladder into the CERN collider, and then a third ladder in a backyard in Pitasch, Switzerland. Sometimes, the tableaux overlap. Two images back to back discuss graves (one in Sasabe, Mexico, one in Lagos). The next, in Brooklyn, depicts a minivan behind a chainlink fence. “For a long time, I avoided having cars in my photographs,” Cole writes. “Now I know they are our shadow on the earth, our prosthesis.” The next image in the sequence, of a Volkswagen outside of Saint Sebaldus, Nuremburg, continues the car theme: “They are ever with us, the cars. We live and die with them, they give us joy.” He then continues: “The three photographs before this one feature or allude to crosses,” and it is only then does one realize that, in the Brooklyn photograph, there is a crossbar visible in the chainlink fence. Cole’s title may invoke the limitations of vision, but the book substitutes one kind of seeing for another one, one in which legibility is built up through layering and multiplication.

“Blind Spot,” in other words, uses the interplay of visual information and textual information, creating connective threads that span the individual locations, multiplying their resonances. Cole’s book seems to ask, finally, what if we took Calvin’s comment about the splinters of the True Cross not as an indictment of fraudulent religious souvenirs but somehow as a literal fact? What if the fragments were greater than the whole — if, by some loaves-and-fishes-type miracle, the True Cross only grew in volume, filling up more and more ships the more it was torn into fragments? For in “Blind Spot,” Teju Cole has succeeded in shredding experience into tiny fragments, all of which add up to much more than the sum of their parts.

Dickey is the author of “Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places,” as well as two other books of nonfiction. He teaches creative writing at National University.

Teju Cole

Random House: 352 pp., $40

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.