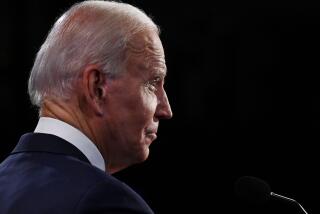

Biden’s regular Joe side

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The personification of the white-haired Washington insider, Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Joseph R. Biden Jr. has spent more than half his life in the Senate, seemingly so in love with his own voice that his colleagues must fight to be heard at his hearings.

A hundred miles away from Capitol Hill, however, is another Joe Biden -- more a character in Mister Rogers’ neighborhood than a globe-trotting statesman or a pontificating fixture on the Sunday talk shows.

He is a putterer who plants bushes in his backyard and designed his own house, including space for his elderly parents. He’s a man quick to find a doctor for someone’s sick grandmother or hold a fundraiser for a local firefighter battling cancer.

This Joe Biden is the son of a car salesman who lost nearly all his money and moved his family from Scranton, Pa., to a hardscrabble neighborhood in Delaware. As a boy, Biden struggled to overcome a bad stutter and the nickname Joe Impedimenta.

As a 29-year-old freshman senator-elect, he lost his wife and infant daughter in a car crash that also severely injured his two young sons. The tragedy almost caused Biden to abandon his political career. And for years afterward, he took the train home almost every night from Washington to Delaware to be with the boys as they grew up.

“I tell people that you get to know Joe Biden the closer you get to Wilmington, Del. And when you see him with his family, then you know the man,” said John Marttila, a longtime friend and advisor who worked on Biden’s first Senate campaign in 1972.

Biden’s family was at the core of his first run for office. His sister, Valerie, ran that campaign, as she has each one since. His brother headed the fundraising operation. His mother and father sat in on most of the strategy meetings.

Biden was challenging a popular incumbent Republican who maintained a huge lead in the polls in a year that would sweep Richard Nixon to his second term in the White House.

The campaign had so little money to advertise, Marttila recalled, that Biden’s army of volunteers had to get mailers to voters by walking neighborhoods around the state. But Biden eked out a victory.

A month later, as he was in Washington interviewing candidates for his office staff, the fatal accident occurred. His wife and three children had been out shopping for a Christmas tree.

Biden didn’t want to take his Senate seat, said Ted Kaufman, another longtime friend who worked on that campaign and would serve as Biden’s chief of staff for 22 years.

Waiting for his sons to recover in the hospital, Biden wrote in his 2007 memoir, “Promises to Keep,” he would take long walks around the seedy neighborhoods nearby. “I liked to go at night when I thought there was a better chance of finding a fight,” Biden wrote. “I was always looking for a fight. I had not known I was capable of such rage.”

The loss also shook his deep Catholic faith. “I felt God had played a horrible trick on me,” he wrote.

Montana Sen. Mike Mansfield, the Democratic leader at the time, convinced Biden to stay in the Senate. (He was sworn in at one son’s bedside in the hospital.) But Biden resolved not to be separated from his family. He gave up a house that he and his wife had planned to buy in the capital and instead went back to Delaware every night.

“The rule in the office was if the boys called, he was to be interrupted no matter what he was doing or who he was talking to,” Kaufman said. “He was never out of communication with them.”

Biden’s father, a proud man who had made his children talk about foreign affairs around the dinner table, would frequently come down to the Capitol to see the young senator, sitting in on his son’s hearings and other meetings. “His dad loved it,” Kaufman recalled.

Under the tutelage of Mansfield and other senior senators such as Minnesota’s Hubert H. Humphrey, Biden quickly landed plum committee assignments.

The ambitious young senator showed an early affection for the limelight. After traveling with five other senators to Moscow in 1979, Biden emerged from a meeting with Premier Alexei Kosygin to tell reporters of the arms control demands he had put to the Soviet leader.

By the late 1980s, Biden was chairman of the Judiciary Committee, a post from which he presided over the controversial Supreme Court confirmation hearings of Robert Bork and Clarence Thomas, both of whom Biden opposed.

Biden was accused of mismanaging the 1991 Thomas hearings, which erupted into a dramatic examination of Thomas’ alleged sexual harassment of Anita Hill.

But Biden had burnished his image as a Capitol Hill eminence. He would push through major legislation to combat domestic violence and the drug-fueled crime wave.

From his position on the Foreign Relations Committee, he cooperated extensively with several Republicans, including the late conservative Sen. Jesse Helms, with whom Biden worked on a major chemical weapons treaty.

The high-profile committee hearings and television appearances that Biden sought so assiduously never seemed to help his political fortunes nationally. He was crushed in both his presidential bids, in 1988 and this year.

And Biden never really became a Washington insider. He is not a major fundraiser in the Beltway and gets relatively little money from political action committees. Among his biggest supporters have been employees of MBNA, a Delaware-based credit card giant recently bought by Bank of America.

Biden doesn’t move in the Washington cocktail circuit. And when he remarried and started a family with his second wife, Jill, he still returned home to Delaware nearly every night.

“He knew every conductor on the train,” said Mark Gitenstein, who worked for Biden for 13 years and remains close to him.

To this day, Gitenstein and others who know him say, Biden keeps up with the people back home.

One is J.D. Howell, a former chief at the Mill Creek volunteer fire company outside Wilmington.

In 1988, Biden suffered a brain aneurysm. Howell was a member of the ambulance crew that rushed him from Delaware to a Washington hospital, where doctors performed lifesaving surgery.

Fifteen years later, long after Biden had bounced back, Howell was diagnosed with advanced stage lymphoma. Biden called immediately.

“The man was practically at my doorstep,” Howell recalled Saturday before reading a letter the senator sent him at the time. “You wouldn’t let me quit on that fateful night . . . ,” Biden wrote. “Now it is my turn.”

When his fellow firefighters held a benefit for Howell, Biden and his wife came to preside.

“It was kind of an emotional thing,” Howell said, “because Joe knows what it’s like to be down and out.”

--

--

Times staff writers Dan Morain in Sacramento and Chuck Neubauer in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.