Legacy of Violence Follows Children of Gang Members

- Share via

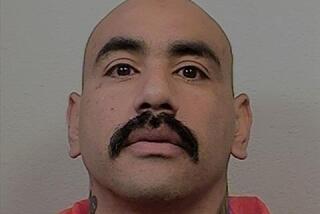

The burly gangster known as P-Loc only wanted the best for his little boy.

When the child was just a year old, his ear was pierced just like daddy’s. By the time he was 2, his father had him sporting the baggy blue pants with sharp creases favored by the Crips.

Before long, the homeboys were calling the youngster Li’l P and slipping him dollar bills. Thanks to his father’s reputation, the youth had a line of credit at the burger stand in his South-Central Los Angeles neighborhood.

“It was like this was my little son, my little right hand, someone I’ll live and die for,” said P-Loc, who wears thick gold chains and the name of his gang--the Kitchen Crips--tattooed across his chest. “It seemed cool to me at the time.”

Now 24, P-Loc works part time doing security and maintenance, his gangbanging days behind him. He regrets having steered his son toward the gang life and hopes that the boy, now 6, was too young to remember learning the rituals of the streets.

Yet the legacy inherited by P-Loc’s son--like the teardrop tattoo by his father’s left eye--is not easily erased. He belongs to the first generation of children born to gang members since Los Angeles’ street rivalries exploded in the 1980s--kids whose parents fueled the culture of crack cocaine and drive-by shootings.

Although all children in troubled neighborhoods are exposed to risks, the children of gang members must go through life with a parent whose face alone can draw gunfire.

Sometimes the youngsters fall victim to those attacks, as was the case this month for two baby girls slain by gang members allegedly aiming for their fathers or their father’s friends. Many more are left to grow up with a dad behind bars, and for thousands of other children, with only a grave to remember him by.

“The future for these kids is on a thin line,” said Cynthia Mendenhall, 30, a former gang member known as Sister who runs a program for children from broken families at the Imperial Courts housing project in Watts. “Out of every unit here, death done touched on every door.”

Gang members do not wish any of this on their children. Often keenly aware of their own mortality, they speak of their youngsters with the protective instinct of any parent who dreams of a brighter future for the next generation. “Don’t nobody want their kids to grow up like this,” said Big Looney, 18, a father-to-be, as he stood with friends on a street corner the other day drinking malt liquor.

Still, many of those same parents are unable or unwilling to show their children another way of life, say gang and law enforcement authorities. Frequently, the only thing gang members have to offer their heirs is gangsterism--a world that, for all its madness, provides a powerful sense of identity and belonging.

“I’m convinced that their dream is that their children not live in violence, but they fear it’s not going to be possible,” said Father Bill Easterling, a Pomona priest who has buried children ages 4, 2, and 1 1/2, all killed in the last few years as a result of gang attacks directed at a parent or older relative. “All they feel they really have to give them are things like honor, pride in their turf and their relationship with the gang.”

There are some gang members, weary of the bloodshed and deceit, for whom parenthood can be a wake-up call--a graceful excuse for withdrawing from the criminal life without losing respect on the streets.

Vince Ibarro, 19, who is known as Wizard on the streets of his East Los Angeles neighborhood, is determined to protect his girlfriend, Rosa Campos, 17, and their 8-month-old son, Vince Jr.

“It’s too late for me now, but not for my son,” said Ibarro, who was shot in the thigh by rival gang members at a miniature golf course before Campos was pregnant. “I just have to get them out of here. Have my own place.”

But even well-meaning parents can unwittingly expose their children to danger, as rivals may still note a gang member’s past affiliations and perceive him as fair game. As most gangsters are ready to admit, their look--the attitude, the walk, the talk--does not disappear just because they have laid down their guns.

“Like I could be walking down the street and someone would see that I got a tattoo on my neck and say: ‘Let’s hit him up,’ ” said Frank Hernandez, 24, a father of three, who is trying to sever his ties to a Pacoima gang. As a safeguard, he wears turtlenecks when he takes his children to the shopping mall.

“I don’t wish this life on anybody,” he said.

Michael Haley, whose 18-month-old daughter, Sabrina, was fatally shot while their car was stopped at a traffic light this month, managed to shed his gang ties but not the look.

Haley, 19, grew up in Compton, where, he said, he was involved with a gang but left several years ago to straighten out his life, working nights as a security guard. He was returning Sabrina to her mother’s house on April 8 when another car pulled alongside at 48th Street and Avalon Boulevard.

At least six shots exploded. Haley tried to shield Sabrina, but a bullet struck her in the head.

“I thought I left that all behind,” said a somber Haley, his head bowed as he sat outside his apartment wearing a crisp T-shirt and plaid shorts on a recent day. “I just wanted to be a father to my kid.”

Los Angeles police do not believe that the assailants recognized Haley, and no words were exchanged. The two suspects--both of whom are being held without bail on murder charges--simply decided that Haley looked like a gang member and noted that he was driving a car whose color is associated with a rival gang, Detective Carl Sims said.

A similar attack occurred last week, when a suspected gang member drove his car into a man holding 5-month-old Lashanique Leverett, killing the infant. Her mother, only a few feet away, described the man holding Lashanique as the girl’s “god-brother.” Police also said he is a gang member. No arrests have been made.

“They know that as long as they’re riding around the neighborhood with their kid and old lady in the car, they’re all targets,” said Jim Galipeau, a deputy probation officer. “But they don’t think about that. It’s like being in combat--if you think about death and dying every day, they’re going to haul you away in either a body bag or a straitjacket.”

For Joel Chaparro--who sports a necklace-like tattoo across his throat reading, “There’s a thin line between love and hate”--having a baby means a piece of immortality in what may be a shortened life. His girlfriend of five months recently had a miscarriage and they are trying again.

“It’s something you can love, care, cherish,” Chaparro, 22, said of having a baby. “It’s like that’s your pride and joy right there. . . . The way I look at it, if I was to die or anything like that, at least I would have someone to carry on.”

For those parents whose identity is most deeply intertwined with the gang, raising a child is akin to grooming the youngster for the streets. Ears, for both boys and girls, are pierced as an infant. They are given a nickname and dressed in the style of the neighborhood gang. Later, they are taught to flash the gang’s hand signals and write their placa, or moniker, on the wall.

Those traditions are most common in longtime Latino gangs, say authorities, who have noted as many as four generations active in some Eastside communities. “You’ll go in and see a picture of grandfather on the wall, dressed in full-on cholo style,” said Housing Authority Police Officer Kent Keyfauver, who works at Ramona Gardens. “The flame just gets handed down from one generation to the next.”

In black gangs that genealogy is not as entrenched. Still, youngsters will sometimes be given red or blues rags to tote around and might be dressed in flashy tennis shoes whose brand names are imparted with a sinister double meaning--British Knight for “Blood Killers,” Calvin Klein for “Crip Killer.”

“Some kids, the first word they know is cuzz, “ said Ed Turley, a manager for Community Youth Gang Services, referring to a common form of address among Crips. “They are taught from infancy to know their rivals.”

Because most gang members do not do that much parenting to begin with, the fate of their kids is often in the hands of the child’s mother. If she, too, has fiercely loyal affiliations, the child will likely be thrust toward the gang. But if the woman is a moderating influence on the gang member’s life, as is commonly the case, the child may be steered toward less destructive pursuits.

“Meeting the right female--that was a major factor that slowed me down,” said Kenneth Riley, 31, a father of seven who is head counselor at Youth Intervention Program, an alternative high school on Slauson Avenue. “I had people dying around me every day. Now, I want to see my kids grow up.”

Last year, when Riley’s eldest son, now 12, was being pressured by the neighborhood youths to join a gang, Riley went looking for the gangsters and told them to lay off.

“I told them who I was and where I used to be from,” Riley said. “I didn’t care what they wanted to do, but this is my son and he ain’t gonna be in no gang. I haven’t had any problems since.”

For all the danger imposed on children by their parents’ gang affiliations, perhaps the greatest risk they face is growing up without a father.

P-Loc’s son was born while P-Loc was in jail. Here’s your da-da, the boy’s mother would say, pointing to a photo. When P-Loc got out, he went to visit the child. “I said: ‘Where’s your daddy?’ ” P-Loc recalled. “He pointed to the picture.”

Lupe Rivas, an 18-year-old high school junior, feared the worst after she gave birth two years ago to Richie. She urged his gangbanging father, Richard Ortiz, to come in from the streets. For a while he did, Rivas said, “but then he just got bored or something.”

When she got pregnant the second time, she gave him an ultimatum. “I told him it was either his friends or me,” she said. Ortiz, known on the streets of Boyle Heights as Sniper, chose the friends.

Last year, his homies buried him after he was gunned down by rivals. In November, Rivas gave birth to his daughter, Justine.

Asked of her dreams for her children, Rivas said: “Away from here. Away from all the violence.”

Family planning is not usually a high priority for most gang members; some men may even consider birth control as an affront to their manhood. But in some neighborhoods, where gang violence has taken a staggering toll, community workers have noticed a rise in teen-age pregnancies--a trend they view as a subconscious reaction to the killing.

“You get a kid who feels on some level, ‘I won’t live to see 20,’ ” said Father Gregory Boyle, a priest at Dolores Mission in Boyle Heights. “He wants to see junior now.”

Jose Avitia, 18, known as Flaco around the Pico Gardens housing project, and his 17-year-old girlfriend, Nancy Paez, are among the young couples who hope that a child will provide an exit from the carnage.

Recently, they gathered on the sofa, as friends and family lavished them with gifts at a baby shower. The guests applauded when the father-to-be sheepishly pulled out a tiny suit of jumpers from its pastel wrapping.

“I wanted to have a baby so I could have a really good reason to get away from all this, you know,” said Flaco, as he showed off a small crib rimmed with fuzzy animals. “I’m gonna try to make life wonderful.”

But it will be a difficult transition. Later that evening, as Flaco’s parents prepared carne asada in the back yard to the beat of Mexican rancheras, his homeboys arrived.

They were cautious about intruding on a family gathering, choosing to keep a respectful distance. One at a time, Flaco filled a plate with meat, salad and beans, and carried it to them in the shadows.

On Tuesday, the couple’s son was born. They named him Richard--a tribute to Nancy’s brother, slain by gang rivals two years ago in a pizza parlor shootout.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.