After 25 Years, the Harsh Lessons of Carson’s ‘Silent Spring’ Endure

- Share via

SPRINGDALE, Pa. — Twenty-five years ago, a quiet woman with a lifelong “sense of wonder” about nature published a book that explained clearly, for the first time, what was happening to the birds and the bees.

They were dying.

Many of them shuddered in the grip of chemical poisons and dropped from the sky. Rachel Carson’s book, “Silent Spring,” warned in lucid terms of an imagined spring in which “only silence lay over the fields and woods and marsh.”

Almost overnight, the book provoked a nationwide outcry against DDT and other man-made pesticides and herbicides. Today, its author is revered by many as the spiritual mother of the nation’s environmental movement.

‘The Right Message’

“She was the right person with the right message at the right time,” said Robert Blake, a former ambassador and assistant U.S. secretary of state who became an environmental activist in the 1970s.

“She forced the issue of environmental contamination . . . of the countryside into the political dialogue of the country for the first time,” agreed Gaylord Nelson, a former U.S. senator from Wisconsin who organized the Earth Day celebration in 1970.

Carson died in 1964, but the 25th anniversary of “Silent Spring” this year finds some environmentalists lamenting that federal regulation of her immediate target, pesticides, has lagged.

“It’s somewhat ironic,” said Jay Feldman, coordinator of the National Coalition Against the Misuse of Pesticides. “We’ve lauded Rachel Carson as a prophet, and yet 25 years later we haven’t heeded her advice.”

Weak Law on Pesticides

In May, the National Academy of Sciences issued a report that said the Environmental Protection Agency had failed to eliminate 98% of the theoretical risk of developing cancer from pesticide residues on food.

One reason, Feldman said, is a pesticide control law he calls weaker than federal statutes protecting the air and water.

“The pesticide problem is a hidden problem of chemicals widely spread in low levels throughout the environment,” he said. “It’s not as clearly seen as dirty air or an overflowing water site with dead fish in it.”

As someone who saw the dangers clearly, and wrote of them eloquently, Rachel Carson was quietly honored on what would have been her 80th birthday May 27 in her verdant hometown here on the Allegheny River.

Fragile Health

Her former classmates at Pittsburgh’s Pennsylvania College for Women, now called Chatham College, remember her as a plain woman of fragile health, with a puckish sense of humor and a passion for her studies. She never married and lived with her mother most of her life.

“The thing that’s so remarkable about her is that she was ordinary,” said Dorothy Seif, 80, who befriended Carson when the two discovered a mutual interest in biology.

“I remember we were working late one night in the laboratory, and she stopped and looked through the darkened window. She said, ‘I’ve always wanted to write, but I haven’t much imagination. Biology has given me something to write about. I’d like someday to make the animals and plants and woods as interesting to others as they are to me,’ ” Seif recalled.

‘Took Delight in Life’

“People are always trying to make her out as a raging reformer, which is precisely the opposite of what she was. She said one crusade in a lifetime is enough,” said Shirley Briggs, who worked with Carson when she was an editor at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in the 1940s and ‘50s.

“She was more fun than just about anyone else I ever knew. She took such keen delight and enjoyment in life,” Briggs said.

Carson wasn’t known as an activist before the publication of “Silent Spring” in 1962. She had written three non-controversial books about the sea.

One day, she received a letter from a friend in Massachusetts who complained that a DDT spraying program intended for insect pests was also decimating the bird population. Curious, Carson discovered similar allegations elsewhere.

Introduced Ecology

“She had other things in mind to write, but when she knew what the situation was, she felt that she had to do it,” said Paul Brooks, her biographer and former editor. “She tried to get other people to do it. . . . It just finally turned out there was no other way.”

“There was a kind of fledgling environmental movement before she came along, including wilderness protection advocates. But ‘Silent Spring’ crystallized public sentiment. . . . Everything she said has been vindicated,” said William Ashworth, author of “The Carson Factor.”

“What Carson did in ‘Silent Spring’ was to introduce to the general imagination the concept of ecology: the way the natural world fit together,” writer Geoffrey Norman said in an article in Esquire magazine in 1984.

Carson, who died of cancer at 57, didn’t live to see DDT banned, but she testified at congressional hearings that ultimately produced recommendations to create the EPA in 1970.

Triggered World Awareness

Even some of the book’s early detractors in the chemical manufacturing industry, many of whom attacked it as overwrought and inaccurate, acknowledge its impact.

“Our industry was very much against (the book), but attitudes have changed. They’ve changed because the public and the congressional process have demanded it,” said Jack Early, who heads the National Agricultural Chemical Assn.

“It did have some salutary effect on American and world awareness. It probably triggered the formation of the EPA itself,” said Ralph Engel, president of the Chemical Specialty Manufacturers Assn.

Even so, Feldman and other environmentalists complain that pesticide control has made little headway, despite such incidents as the 1984 disaster in Bhopal, India, where a pesticide ingredient killed at least 1,700 people.

EPA Running Behind

In 1972, Congress ordered the EPA to re-analyze about 600 active ingredients in pesticides mainly because their long-term potential for harm--for example, whether they are cancer-causing--had not been fully evaluated.

Fifteen years later, the agency has completed its investigations of only 12, according to Ann Lindsay, chief of policy in the EPA’s pesticide program.

One major problem is a “unique process” that gives pesticide manufacturers extensive appeals before the EPA can ban a chemical, Feldman said. When the agency does issue a ban, the pesticide law requires it to reimburse pesticide manufacturers for unsold inventories.

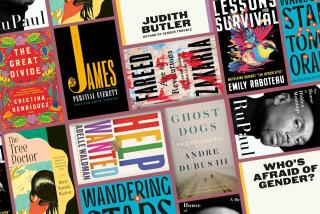

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.