Migrant caravan from Central America, its numbers thinning, slowly moves north in Mexico

- Share via

Reporting from Tapachula, Mexico — A migrant caravan from Central America that has drawn the ire of the Trump administration moved slowly north Thursday, advancing beyond the Mexican town of Mapastepec in southeastern Chiapas state.

The caravan, mostly composed of people from Honduras, many on foot, has thinned since about 7,000 people crossed into southern Mexico from Guatemala in recent days. Many people crossed illegally on rafts across the river that marks the border between the two nations.

Unofficial estimates indicated that some 3,500 to 4,000 people were in the caravan when it reached Mapastepec, about 90 miles north of the Mexico-Guatemala border.

The U.S. border was more than 1,000 miles away. It was unclear what route the caravan would take and at what point the marchers might arrive along the almost 2,000-mile U.S.-Mexico border. Some caravan members may disperse and head to various crossing points, participants said. Some may attempt to catch rides on a northbound freight train, known as la Bestia, or the Beast.

Is the U.S. really facing a border crisis? »

The caravan set off Oct. 13 in Honduras and has made its way through Guatemala and southeastern Mexico, despite broiling temperatures and occasional downpours. Many caravan participants have dropped out because of the difficulties.

At times, the group stretched out over several miles along the Pan-American Highway, which is bordered by mango and banana plantations and pasture carved out of the semi-jungle landscape. The migrants walk and seek rides from motorists and truck drivers, and occasionally jump on public transportation. Some young men hitch rides on semi-trailers, a hazardous maneuver.

At least one caravan member, a Honduran man in his early 20s, was killed after being run over by a vehicle.

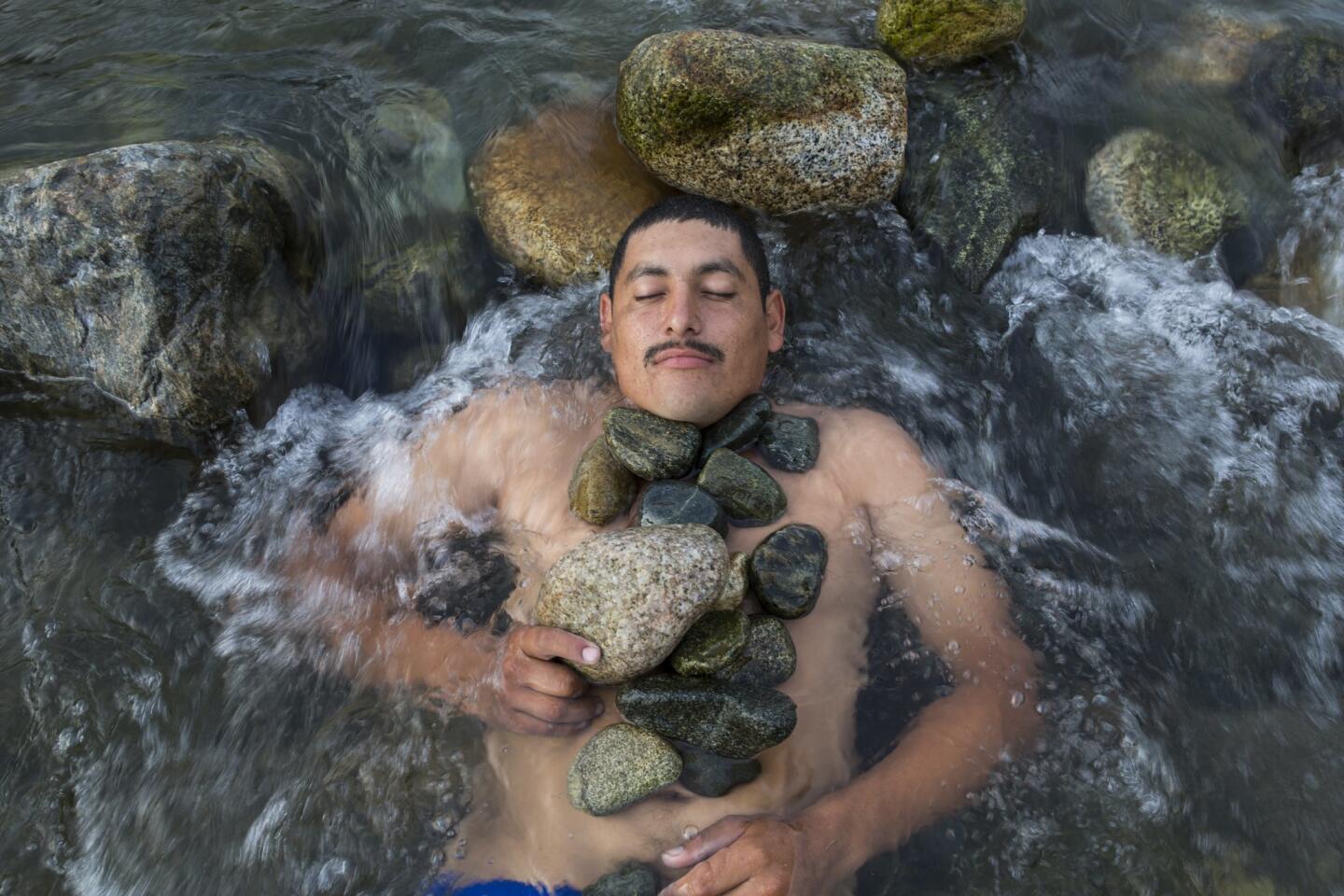

Upon reaching a town, the caravan members typically rest for an evening or more, often staying on streets and in plazas and parks, seeking out shade and shelter. Aid groups, church volunteers and local families have provided food, water and other necessities. Many caravan participants have suffered from dehydration, exhaustion, insect bites and other ailments.

Neither Mexican police nor immigration officials have made a concerted effort to deter the group.

Many caravan participants say they are fleeing poverty and violence in Central America. The Trump administration has characterized some as criminals and economic migrants and say they do not qualify for political asylum in the United States.

More than 1,600 former caravan participants are applying for refugee status in Mexico and are being kept at a sprawling fairgrounds site in Tapachula, about 20 miles north of the border with Guatemala, authorities say.

President Trump has portrayed the caravan’s bedraggled assemblage as a national security threat during campaign appearances in advance of U.S. midterm elections Nov. 6.

Mexican authorities have straddled a line between their avowed respect for human rights for migrants—Mexico is a major source of immigrants in the United States—and pressure from Washington to halt the migrants’ advance.

In the town of Huixtla, about 50 miles north of the Guatemalan border, more than 200 exhausted and ailing caravan participants returned south late Wednesday on four buses. Honduran diplomats in Mexico helped arrange the return trip.

“I would keep on going, but my daughter has a fever and she needs rest to get better,” said Merlyn Guardado, 37, who said she joined the caravan Oct. 14 in Honduras. Like others, she said she heard the news about the caravan on TV, packed up and quickly met the group, along with her three children — two sons, 14 and 9, and her daughter, Meylin, 3.

“I did it for the kids more than anything,” Guardado said while seated in the plaza in Huixtla, cradling Meylin. “There’s no jobs for anyone in Honduras, men or women.”

As dusk neared, four buses pulled up in the plaza in Huixtla to take them back to Honduras.

“We’ll be home at this time tomorrow,” said Guardado, exhausted, disappointed, but also relieved.

Other northbound caravans reportedly have been forming in Central America, despite attempts by authorities in Honduras and Guatemala to thwart such efforts. Trump has said Central American nations could face aid cutoffs because of the northward flow of migrants.

Mexican authorities this week moved to shut off illegal crossings along the border with Guatemala. Mexican immigration authorities were stationed in large numbers on the muddy northern side of the Rio Suchiate.

Among those detained Wednesday by Mexican immigration agents for processing and possible deportation was Claudia Maria Jimenez, 45, of El Salvador, who said her husband vanished in Mexico more than a year ago.

“I just came to look for my husband,” Jimenez said.

Twitter: @PmcdonnellLAT

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.