Mali election is peaceful despite threats from Al Qaeda group

- Share via

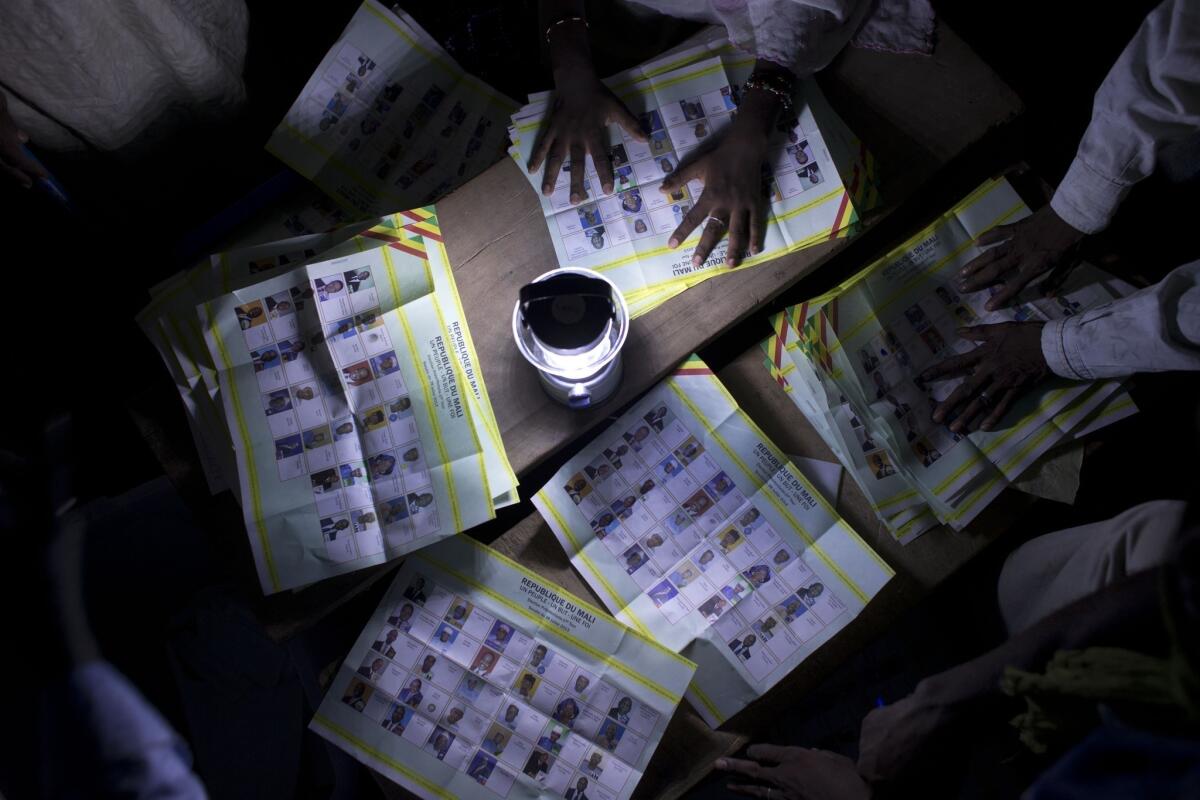

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa -- Expectations of Mali’s presidential election were so low that everyone was pleasantly surprised when the vote passed peacefully with perhaps half of eligible voters participating.

With security tight at polling booths Sunday, there were no violent attacks despite threats from an Al Qaeda-linked militia, the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa.

And, with the country’s peace and stability at stake, the 50% turnout estimated by European Union observers was higher than past election turnouts of around 40%. Turnout in the country’s troubled north, however, was lower.

Former Prime Minister Ibrahim Boubacar Keita is leading the vote count, according to Malian state-owned television. If he fails to gain more than 50% of the vote, a runoff will be held next month.

France -- which sent in troops to oust violent Islamist militias after they seized half of the country last year -- congratulated Mali on a successful election.

No one expected the election to be perfect. Saying the poll wouldn’t be perfect “is a little like saying that a Metallica concert won’t be quiet,” analyst Bruce Whitehouse wrote in his “Bridges from Bamako” blog.

Despite recent calls by the International Crisis Group to delay the election so that it could be better organized, Malian officials pressed ahead, hoping that the vote would be credible enough to return the country to peace, democracy and stability. Two days before the vote, the head of the EU observer mission, Louis Michel, declared that the conditions required for a credible vote had been met.

France, eager to withdraw its troops and hand over responsibility to U.N. peacekeepers, had a high stake in a smooth election.

“Congratulations are in order that the Mali elections went off well. For France, it is a great success,” said French Prime Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault on Monday. French President Francois Hollande said the smooth election “confirms Mali’s return to constitutional order, after the victory scored over terrorists and the liberation of the territory.”

He called the vote “an opportunity and a symbol.”

Mali’s interim president, Dioncounda Traore, said the vote had been the best the country had organized since independence.

However, Sunday’s vote saw several major problems that could raise questions about the election’s legitimacy, particularly in the troubled north. News agencies reported the election was poorly organized and in many cases voters couldn’t find their names on voter rolls. Turnout was low in the key northern city of Kidal, which both Malian authorities and Tuareg rebels occupy under the terms of a tenuous peace deal.

Also, several hundred thousand northern Malian refugees who fled their homes during last year’s fighting were excluded from the vote.

Sunday’s election was the first in this vast West African country of 15 million since Mali almost fractured last year, when the rebellion and coup reverberated chaotically across the country like rapidly toppling dominoes.

A rebellion by Tuaregs in the north exposed the army’s poor equipment and support, triggering a military coup. The rebels exploited the power vacuum caused by the coup to seize half of the country. Violent Al Qaeda-linked militias piggy-backed on the Tuareg rebellion, and quickly asserted control over the north, imposing a harsh form of sharia law.

As the militias swept south, France stepped in with military intervention, declaring that Mali had become a terror haven on Europe’s back step.

The swift French military operation drove the Al Qaeda militias out of the large northern cities and towns. France scored some major victories, including killing an important Al Qaeda-linked leader, Abou Zeid. But violent Islamists militias still unleash suicide bombings in northern cities such as Gao.

If Mali’s north doesn’t accept the election as credible and legitimate, the country will likely remain politically divided, and the fractures that led to last year’s crisis will remain, undermining the transition to a peaceful democracy that the election is supposed to bring.

Kidal is crucial because it’s the base of the Tuareg rebels who, for decades, have chafed under the corruption and remote rule by the political elite in the distant, southern capital, Bamako.

France is planning to withdraw its 4,500-strong military force from Mali in the coming months, with 12,500 U.N. forces taking over the task of securing the country and preventing a resurgence by Al Qaeda-linked militias.

But several key issues remain unresolved. One major problem for the next president is the troubled relationship between Mali’s ruling elite in Bamako and the Tuareg rebels in the north, who are hated by many people in southern Mali because they are blamed for launching the rebellion that led to last year’s crisis.

The election and stabilization of the country is a prerequisite to the resumption of donor aid. The U.S. State Department has indicated $180 million of aid and military assistance would be released to Mali if the election is a success.

For donors such as the United States and European countries, the main worries are that if Mali doesn’t return to stability and democracy, it will once more become a haven for Al Qaeda. But ordinary Malians are equally concerned about bread-and-butter issues such as high unemployment, corruption and poor electricity and sanitation, according to Whitehouse.

Keita, like the other 26 presidential candidates, is hooked into the existing Bamako political elite, rather than the new broom that many Malians want to see.

ALSO:

Pope Francis’ trip to Brazil seen as a roaring success

Russia: President Vladimir Putin catches a really big fish

China’s ‘visit your parents’ law weighs on many in one-child nation

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.