Brazil’s Rousseff takes nuanced approach to foreign policy

SAO PAULO, Brazil — Shortly before Venezuela’s presidential election, former Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva recorded a video supporting Nicolas Maduro, saying he had “stood out brilliantly in the struggle” for a more democratic Latin America.

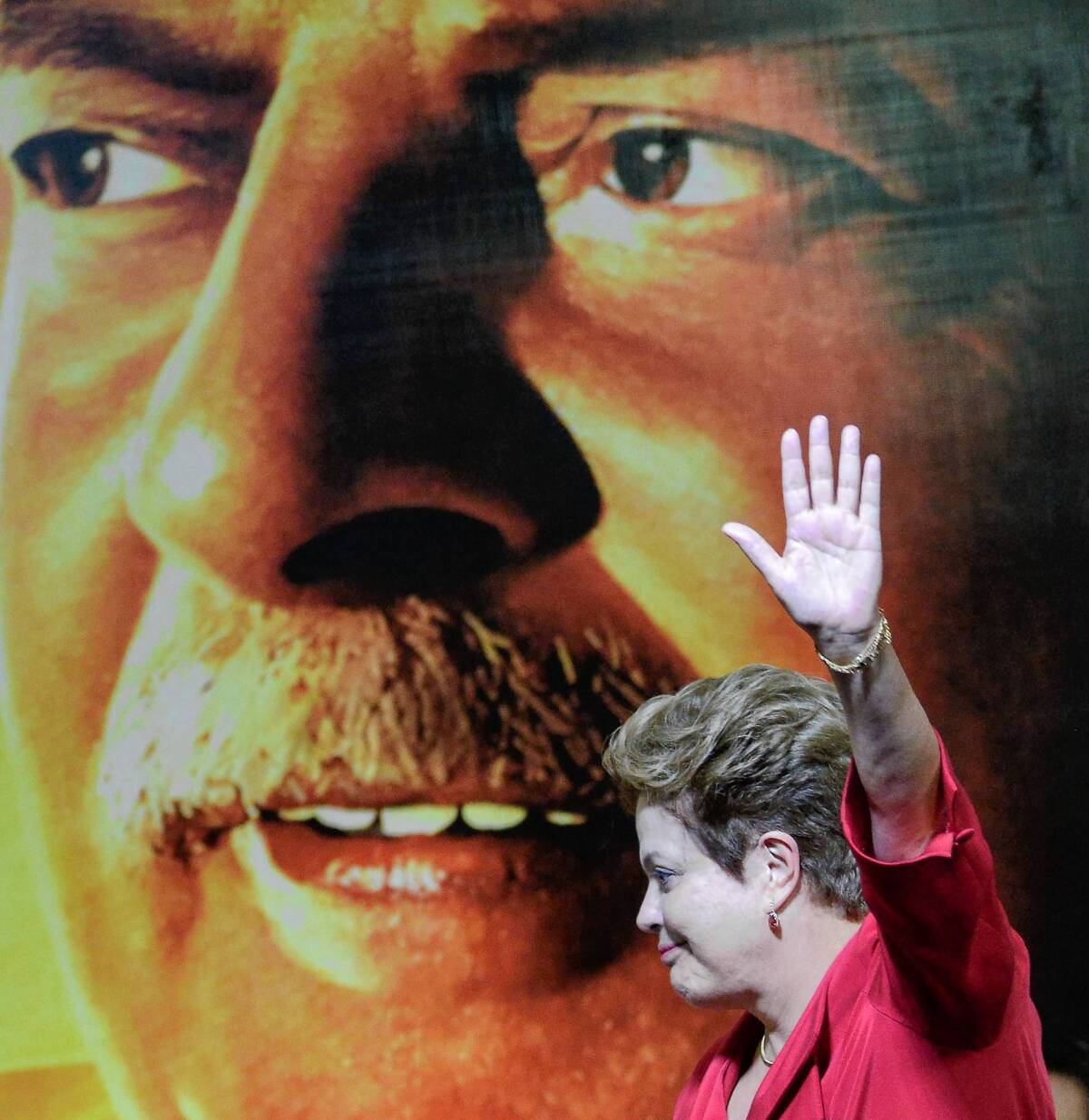

Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff, who was endorsed by Lula in 2010, kept silent on the ultimately victorious candidacy of Maduro, the hand-chosen heir of the late leftist Venezuelan president, Hugo Chavez.

The difference in demeanor between the two Brazilian presidents was not surprising to Rousseff watchers. Since assuming office at the start of 2011, she has taken a much more muted approach to foreign policy than Lula, avoiding the type of activism that often annoyed the United States.

Rousseff, 65, “has a more subtle style,” said Gregory Weeks, a professor of Latin American politics at the University of North Carolina-Charlotte. “Even if they agree on most things, she considers this to be a more effective way of getting what she wants, including from the U.S., than what Lula had done.”

A onetime leftist rebel during Brazil’s military dictatorship, Rousseff has spent much less time on foreign policy, focusing mainly on overcoming the country’s economic slowdown. In two years at the helm, she has spent fewer days abroad than Lula did in his first year in office.

“Lula liked to travel the world and made front-page news,” says Peter Hakim, president emeritus at the Inter-American Dialogue, a Washington think tank. “Dilma is more of a manager-technocrat. She has also pulled back from some of his most public policies, especially his relationship with Iran, which was the source of considerable difficulties.”

In what was arguably his most audacious move, Lula mediated a Turkey-Iran uranium swap in 2010 that he termed an alternative to additional sanctions against Tehran for its nuclear development program. The agreement was dismissed by the U.S., and some have argued that Lula’s intervention may have hurt Brazil’s long-term goal of a seat on the United Nations Security Council.

Under Lula, China replaced the U.S. as Brazil’s main trading partner, and he pushed for the interests of poorer countries against the rich. Known for his brash, folksy style, he sometimes directly criticized the traditional major powers. In a meeting with British Prime Minister Gordon Brown in London in 2009, Lula said the global financial crisis was caused by “white people with blue eyes.”

Lula, an extremely popular president who oversaw a domestic economic boom, also used his standing and charm to very publicly support Venezuela, Cuba, Palestinian rights and the cause of Latin American integration. In the last decade, Latin American countries came closer together under regional organizations, with many also distancing themselves from the United States.

Lula also intervened after a coup in Washington’s traditional backyard. After Honduras’ military deposed left-leaning President Manuel Zelaya in 2009, Brazil offered him asylum in its embassy after he sneaked back into the country.

Rousseff has opted for a different strategy, pulling away from Iran and refraining from making other major international moves. The only exception has been when Brazil joined several nations in expelling Paraguay from the Mercosur trading group last year after its president was removed from office. That action allowed Venezuela to enter the trading bloc.

“That was the only thing close to a substantial move Dilma has made, but it was quite understandable what Brazil’s interests were there. There are very close diplomatic and trade ties involved,” says Igor Fuser, professor of international relations at the ABC Federal University in Sao Paulo, Brazil. “She’s more circumspect and much less daring, and hasn’t tried to play a big role where Brazil doesn’t have immediate interests.”

Analysts say Lula and Rousseff agree on broad foreign policy goals, such as Brazil having more international influence and its support for regional allies including Cuba and Venezuela. Brazil has also urged caution on international military interventions, including in Libya in 2011.

But Rousseff, who is also very popular at home, is more skeptical than Lula of regional integration projects and has kept more of a distance from Latin American friends, says Fuser. When Chavez died, Rousseff praised his contributions to the region but also noted her country and his didn’t agree on every issue.

“The situation has changed for Dilma’s presidency, in many ways because of what Lula achieved,” says Mino Carta, editor of Carta Capital, Brazil’s only major pro-government publication. “Brazil doesn’t need a leader anymore that is always appearing in the spotlight.”

After the Venezuelan election, Rousseff called Maduro to congratulate him, but refrained from the kind of public cheerleading Lula had been fond of. “I don’t think she has any great difficulty with the kind of relationship Brazil has with Venezuela,” says Hakim. “She just goes about it less aggressively and triumphantly than Lula did.”

Her more nuanced approach may pay dividends in relations with the U.S.

Reuters reported this month that Rousseff had been invited on the first official state visit to Washington for a Brazilian leader in nearly two decades. Though not confirmed officially, it may take place in October, Reuters reported.

She would have a lot to talk about with U.S. officials, especially on agricultural trade policy and the U.N. Security Council bid.

“If Dilma is given a state dinner, and something comes out of it other than a little pomp and circumstance,” says Hakim, “then that really would be a big change.”

Bevins is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.